On Literary Festivals and Crossed Boundaries

By Alicia Elliott

As a writer of creative nonfiction—in particular, one who draws very heavily from my own life and experiences—I’ve learned it’s important to determine whether something I want to write about is too fresh, too raw, for me to write. Making art from a wound that hasn’t healed often feels like smearing blood across the page: it’s uncomfortable, almost horrific for both the writer and the reader. I’ve told friends that they’re too close to their subject matter to have enough perspective to write about important or traumatic moments in their lives; I’ve told it to myself. There are essays that have taken me months or years to be able to write in the way they need to be written. There are essays that I don’t think I’ll ever be ready to write.

It’s taken me a long time to write this essay. To be honest, I’m not sure I’m really ready to write it yet. But I’m going to try anyway. If we’re going to be serious about creating inclusive, creative, innovative literary community and spaces, these types of difficult, imperfect essays need to be written, read and responded to.

I want to talk about boundaries generally; literary festivals, specifically.

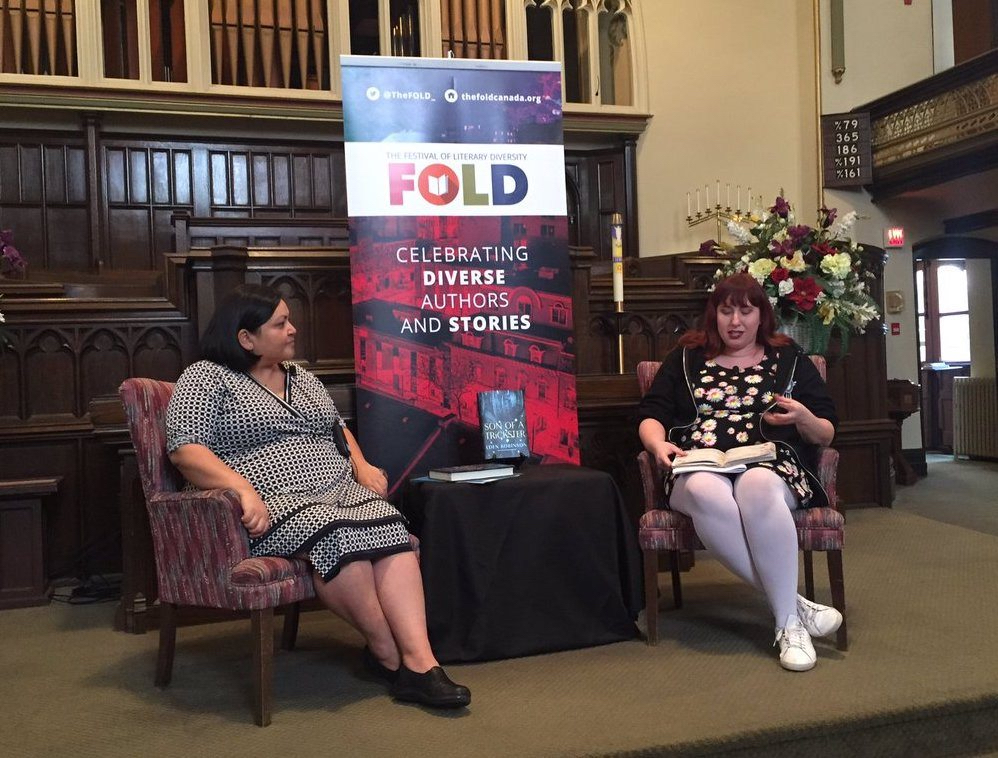

In many ways I feel I was spoiled by my first literary festival experience. I was invited by Amanda Leduc to moderate the Final Lecture with Eden Robinson at the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) before anyone really knew who I was. Though Eden was one of my favourite writers and I’d read everything she’d written, I’d never moderated anything before. For Amanda to ask me to moderate was an enormous act of generosity and trust which I’ll always be grateful for. As an added bonus, I got a festival pass. I went to as many events as I could, eager to soak up this proximity to people I greatly admired. I heard Jen Sookfong Lee, Katherena Vermette, Kai Cheng Thom, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Sheniz Janmohamed, Eden Robinson and others speak about writing and craft in ways that didn’t make their voices feel token; that made them seem like writers, experts on their own work and experiences.

At the time I had no way of knowing this type of experience was the exception, not the rule.

My next literary festival experience was tainted from the outset. When Grit Lit, a literary festival in Hamilton, released their schedule this year, there was a panel listed with a familiar-sounding name: “Is CanLit a Raging Dumpster Fire?” While I wasn’t the first to refer to CanLit in such terms, nor will I be the last, what was strange to me was that the write up for this panel made specific reference to my blog on the subject, which was published on this website—and titled, of course, “CanLit is a Raging Dumpster Fire.” That essay looked at the ways that some of the major issues in CanLit, in particular the ways that Black and Indigenous writers are derided and dehumanized, as well as how women who make claims of sexual assault are presumed to be liars, reflect broader societal issues in what is currently called Canada. It attempted to dismantle the notion that CanLit—and by extension, Canada itself—has ever been as benevolent and accepting as it’s tried to appear.

While I’m sure that the writers that were scheduled to speak about this had opinions worth hearing, it puzzled and hurt me that an essay I wrote on inclusion in CanLit was used to spark a discussion between two white writers. To me, this was everything that was wrong with CanLit: using the intellectual labour of BIPOC writers, particularly women, to give a platform to white people. Having conversations about us without asking for our input or our lead. Putting those who aren’t really affected by these conversations into positions where they’re setting the agenda and leading the conversation. I wondered whether I was clear enough in my original essay for people to understand what I was saying; after all, if I was, why would they be using my words this way?

Grit Lit, for their part, did reach out to me and apologize. What’s more, they offered for me to come in and speak about the problem at the festival. This was an offer I felt very apprehensive accepting. My mental health wasn’t in the best place, and I kept telling myself over and over that I was creating these situations. I was overreacting. I was making problems where there were none. I was to blame. Anyone who’s familiar with anxiety and depression will recognize this sort of cyclical negative self-talk. I’d contend, however, that the interlocking systems of white supremacy, settler colonialism and extractive capitalism encourage BIPOC writers to feel this cycle of self-hate and self-blame all the time. We must constantly be aware of the ways that our own emotions can be used against us, which means we must know how to essentially dissociate from ourselves whenever we encounter racism, misogyny, etc. in professional settings.

Knowing all of this, I was worried that, if I were in a position where I had to explain once again that marginalized people deserved to be treated with humanity, I might become too emotional, too angry; I might yell; I might cry. I might become the Angry Indian Woman™ in front of an entire room of strangers—my dehumanization on display for the cost of a festival pass.

And yet I felt that if I refused the invitation to speak at Grit Lit, I would be perceived as bitter. I would be perceived as someone who points out problems but provides no solutions. I would be perceived as a hypocrite, who preaches tolerance and dialogue and yet hides when those same things are demanded of me. In other words, I would still become the Angry Indian Woman™.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I decided my best course of action would be to accept the invitation to Grit Lit—as long as Jael Richardson and Carrianne Leung, two writers and people who I very much respect, were on the panel with me, which was now titled, “CanLit Is a Raging Dumpster Fire.” Of course, I was still worried about how this conversation would go. In fact, because of this, I originally didn’t want to have a question and answer period at the end. For me, that would introduce too many variables: people innocuously asking hurtful questions, people intentionally asking hurtful questions. I could see this future before me and it made me physically ill.

The night before the panel I barely slept. Anxiety manifested in my body, making me nauseous, sick. Up until I was in the room where the panel was happening, I considered cancelling. Both Jael and Carrianne assured me that if I wanted to cancel, I could. But despite my instincts, I decided to carry on. Despite my instincts, I agreed that we could have audience questions – provided that the person actually asked a question, and they were willing to actually listen to the answer.

When the time for audience questions actually came, Jael was very clear about establishing these boundaries. It only took three people before they were disregarded entirely. A man spoke at length about something banal enough to forget the details, but memorable in the way his words felt: like Carrianne, Jael and I were wrong in our assessments of our experiences in CanLit. When I interjected to ask if he had a question, he hastily spit out the vague inquiry: “What are you excited about?” I refused to answer the question, as it was clear he wasn’t interested in our perspectives; only (publicly) giving voice to his own.

Immediately after that, an older white woman stood up and proceeded to tell us that we were wrong to not have optimism in the future of CanLit. She gaslit us in front of the entire room—claiming that we said things we didn’t say about the Writer’s Union of Canada, despite us and audience members assuring her that she was wrong. She said she thought she was coming to the cancelled panel, as if her not reading the name of the sign outside the room, nor listening to the festival director describe how this panel came to replace the old one, was our fault. She spoke at us—not to us—for what felt like ten minutes, demeaning us in front of the room.

The festival director did not ask her to stop or leave. The festival volunteers did not ask her to stop or leave. An Indigenous woman, a Black woman and a Chinese woman were sitting there in front of an entire room of people being told by a white woman that our opinions on the industry we work in were wrong and that Canada and CanLit were not racist—and no one did anything.

Eventually she sat back down, though I don’t remember why or how. The two audience members who spoke after her, though I believe they were trying to be supportive, also ignored our boundaries. Neither of them had questions, and instead used their time to give their own opinions on the events that transpired. I felt like I wanted to vomit. I was shaking. And like that, the panel ended. People came up to me afterward and told me how great we were—as if that traumatizing and disruptive event didn’t happen. No one asked if any of us were alright. Our panel had become the very thing I didn’t want it to be: BIPOC trauma porn. It took me days to recover—much longer than my pay for my participation could compensate for. No one from the festival reached out to me afterwards to apologize or even check that I was okay.

I’m talking about this situation because it is not an isolated incident. When I was at CWP this year, there were racist incidents on the premises. There are writers I know who have decided not to go anymore because of racism they or their friends have encountered. A BIPOC woman who won a free ticket via the CCWWP’s lottery system spoke about how she probably wouldn’t be able to attend next year because the fees to attend were too high. I wonder how many other marginalized writers were in her position this year, or the year before, or the year before. I wonder how many are in her position for every literary festival or conference: on the outside, looking in.

Literary festivals and conferences are a great way for readers to connect with writers, or emerging writers to connect with established writers. But they’re also opportunities for people who have been led to believe their every thought—no matter how uninformed—should be given voice, to antagonize marginalized writers. Obviously, there has to be room for disagreement between panelists and audience members. But there is a significant difference between asking a question which makes a writer consider another point of view, and a temper tantrum where an audience member treats a panelist with disrespect for nearly ten minutes. That literary festivals and conferences have no way to differentiate between the two, no methods to deal with these situations when they arise, and no code of conduct are all signs that they are not ready to be the inclusive spaces they claim they want to be.

Tokenized inclusion is not enough. It’s the absolute bare minimum. If festivals and conferences are not committed to anti-discrimination—that is, the practice of using de-escalation tactics to stop discrimination outright during every event—why should marginalized writers give you the privilege of our work, our thoughts, our time, our brilliance? If the emotional cost of attending your event leaves us feeling awful for hours or days or weeks, is the fee you pay us really worth it? What are the responsibilities that a literary festival or conference has to the writers it invites to speak?

Finally, how can literary festival organizers and volunteers prove that they take our safety and well-being seriously?

I’m sure I’m not the only one eagerly awaiting answers to these questions.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Alicia Elliott is a Tuscarora writer living in Brantford, Ontario with her husband and daughter. Her literary writing has been published by The Malahat Review, Room, Grain and The New Quarterly, and her current events editorials have been published by CBC, Globe and Mail, Maclean's and Maisonneuve. She's currently Associate Nonfiction Editor at Little Fiction | Big Truths, and a consulting editor with The New Quarterly. Most recently, her essay, "A Mind Spread Out on the Ground" won a National Magazine Award.