On Productivity

By Alicia Elliott

A few months ago I quit my safe, reliable customer service job at Starbucks to focus on writing. I’d just received a grant and I was ready to go full-throttle towards finally writing a book. Those last few weeks of making lattes leading up to my last day, I dreamed up how my ideal day would look: I’d wake up, work out, get breakfast, answer emails, write, eat lunch, write, eat dinner, then have the rest of the night to myself.

I was an idiot.

It’s now been a few months and I’ve had exactly zero days unfurl that way – which obviously has made me feel like shit. The reasons are numerous: getting my daughter ready for school, getting her ready for dance class, household chores, family obligations, meals that don’t make themselves for some reason, that field trip I said I’d chaperone because I was so flattered one of my daughter’s friends called me “cool” last time and who doesn’t need an ego boost now and then… the list goes on and on.

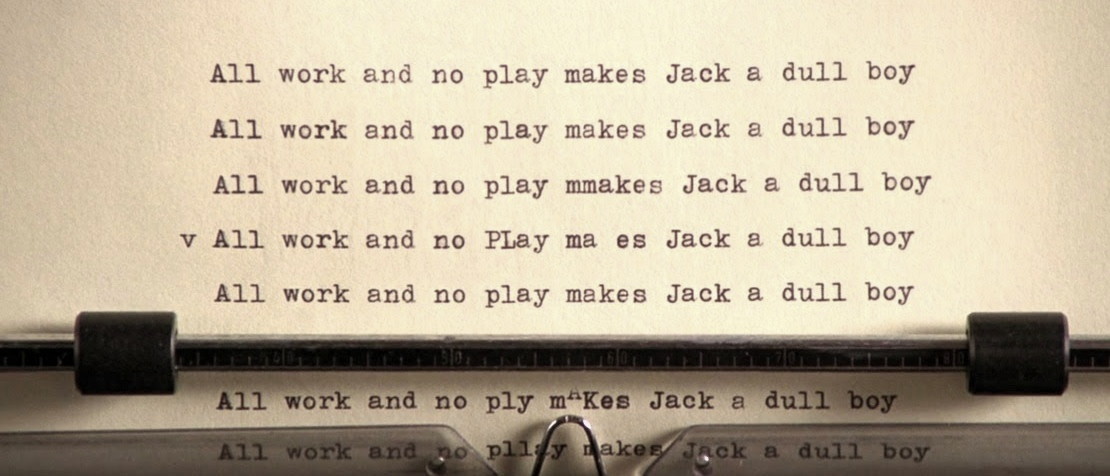

I was still writing the whole time, but it was nowhere near how much I’d imagined I’d write, nowhere near what I’d imagined I’d have accomplished. The guilt was overwhelming, all-consuming and exhausting. It got to the point that any time I wasn’t writing – even when I was at a family birthday party or buying groceries – I was telling myself, “You could be writing. You should be writing.”

Anyone familiar with anxiety or depression knows this tricky brain logic. “Should” statements can lead to anxiety or depression, causing the person who has them to fill with panic about all the ways they’re currently failing. In my case, I thought that I should be writing basically all the time, and if I wasn’t doing that, I was wasting my potential and failing everyone. Since no one can possibly write all the time, particularly if they want to maintain healthy relationships with those closest to them, you can see how this thinking would be problematic, to say the least.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Unfortunately, this pressure to continually produce isn’t just an internal one. The society we live in highly values work and productivity – so much so, in fact, that the question we most often ask a person after we get their name is “What do you do?,” as if knowing how a person pays their rent gives insight into their personality and inner life. But we are all more than how we make a living, and our lives are more than can be measured in the amount of words we write in a day, or the number of books we sell in a financial quarter. Sure, those things are a part of our lives, but when they become the crux of our lives, the means by which we measure our success and self-worth, how does that impact our art? How does that impact our mental health?

Obviously, in the world we live in, we need to have an eye on our finances, as we all have to make a living. But can we be okay with, for example, not having a ready-made answer to the inevitable question all artists and writers ask one another: “What are you working on?” Can we change our conceptions of what the word “work” entails so that experiencing life and art first-hand – experiences which we draw from when we create our own art – is viewed as just as essential to our process as the physical crafting of that art? Maybe then we can stop guilting ourselves for not constantly writing and start enjoying what fuels that writing: living our lives.

It's hard to restructure our priorities and mindsets to give ourselves time to be creative, to explore, to learn without a clear goal or destination or project in mind – but it is necessary. Perhaps before we storm ahead into the next opportunity for glory or recognition, torturing ourselves with all of the things we should be doing to reach that next rung, we should actually take a moment to be grateful for what we've achieved and accomplished. Not just artistically or professionally; personally, as well. Did you have a really great time playing board games with your kid? Watching Game of Thrones with your partner? Reading the latest Heather O’Neill book by yourself? Not all of this looks or feels like work – and it shouldn’t, but all of it helps our work in ways we can’t possibly understand or measure. Accepting our paradoxical need to not write in order to write can help us become healthier and, ultimately, more creative. After all, we are people who are artists, not art assembly lines housed in the bodies of people.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Alicia Elliott is a Tuscarora writer living in Brantford, Ontario with her husband and daughter. Her literary writing has been published by The Malahat Review, Room, Grain and The New Quarterly, and her current events editorials have been published by CBC, Globe and Mail, Maclean's and Maisonneuve. She's currently Associate Nonfiction Editor at Little Fiction | Big Truths, and a consulting editor with The New Quarterly. Most recently, her essay, "A Mind Spread Out on the Ground" won a National Magazine Award.