Remembering Steven Heighton and the Vancouver 125 Poetry Conference

By Shazia Hafiz Ramji

One of the jokes I have with myself is that my first exposure to the public world of poetry was so traumatizing that I had no choice but to accommodate what I saw, however subconsciously. Ten years ago, I attended what would have been my first official poetry conference, the Vancouver 125 Poetry Conference. I distinctly remember being seated for several hours on a weekend morning from something like 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. without a lunch break. The atmosphere was so intense in the conference room at SFU Woodwards, which had opened only a year prior. I remember constantly wondering if we would get a break. I was a smoker then and had an itch to be outside and have a cigarette, but more than that I remember needing to eat.

The doors did not open. There were fist fights between poets (actually). There was a war between the lyric poets and the experimental poets, a distinction I feel is so irrelevant and useless now. But then I take a look at my own Port of Being, which contains both styles, and thus the joke with myself: I gravitated towards lyric and experimental styles equally so that no one starts any fist fights with me (haha?). These tensions were so present in and around the time of this conference, which took place in 2011, a year before CV2 magazine would give me my first official poetry publication. As a baby poet in 2011, the Vancouver 125 Poetry Conference and the tensions in and around it were formative for me, despite the arbitrariness of the lyric / experimental divide now. What I remember too was that I first saw Steven Heighton at this conference. I didn’t realize how much of an impression he made on me until recently.

Steven Heighton has always been a poet who reminded me of my own mortality, so when I first heard he died in April, I felt betrayed. It’s not as if I kept Steven’s books by my bedside or turned to them often, but I did turn to them when the time called for it. For example, around 2014, when I had my first near-death experience due to addiction, I had Steven’s book with me in the hospital. I memorized “Gravesong” from the The Address Book and turned to it to remind me what I needed to do: to live.

Gravesong

Jan. 02

It’s said that the dead want us worthy of something.

Why do you wait till the waiting fills the years?

Pain shovelled deep has no chance to bloom open.

A grave, a stringless guitar, a lost song.

Enough. They must hate to see us here sleeping.

Why will you stall till the stalling’s your life?

It’s wake yourself now or never be woken.

Lifetimes you waited for the right phone to ring.

The drowned, it was said, could be heard at night singing.

Why do you never set out while you can?

It’s fix yourself now or always be broken.

A grave, a stringless guitar, a last song.

(from The Address Book, 2004)

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

What I remember of Steven from the conference was his attitude towards his work. I don’t remember exactly what he said, but I distinctly remember that he repeatedly evoked humility and the importance of being humble. He was someone who understood that every creative act is an one of surrender, that what we do as poets is bigger than ourselves. I know now that this is the most difficult thing to do when face to face with one’s art, because it requires an unlearning every single time – a willingness to go where you haven’t been before, to live with not knowing, to find out what you want to say even if you think you know what you want to say and how you want to say it. It’s the opposite of expertise and mastery, which is what we are encouraged to aspire to, inside and outside of institutions.

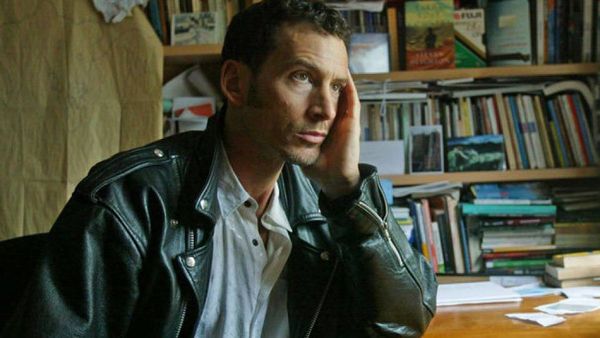

I remember Steven in his black leather jacket. I remember his no-bullshit calmness. I also remember his biting humour:

“Ignore Lord Byron, who wrote that “We of the craft are all crazy.” He was largely right, of course; ignore him anyway. To romanticize the Writer as pursued by the Furies, enthused by the Muses, beset by demons – this is nothing but professional self-importance and self-pity. Writers have no monopoly on poverty, humiliation, self-doubt, or aggressive inner demons. Close your door and get on with it.”

(from Workbook: Memos & Dispatches on Writing, 2011)

Thanks to Steven, I have been able to close my door and get on with it.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji’s fiction was shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s 2022 Open Season Awards. Her poetry was shortlisted for the 2021 National Magazine Awards and the 2021 Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry. Shazia’s award-winning first book is Port of Being. She lives in Vancouver and Calgary, where she is at work on a novel.