What We Owe To One Another

By Amanda Leduc

In the immediate few weeks and months after the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) takes place in Brampton each May, I’m always struck by a strange feeling, something that’s equal parts euphoria, complacency and unease. Euphoria because my work as the FOLD’s Communications Coordinator is always a high during festival season. Complacency because it’s so easy, in the glow of festival aftermath, to feel as though the world is really changing—as though we’re all of us actually in this together, ready to dismantle the structures that we’ve known in the worlds of Canadian writing and publishing and see something new in their place.

Inevitably, though, there is also unease as the days go by and we settle back into the old CanLit system, the one where the voices that we don’t often hear continue to be pushed to the sidelines or ignored altogether. It’s the unease that flares for me whenever I hear about literary events that aren’t accessible, or see a line-up at a panel or festival that isn’t nearly as varied as it could be. It’s the unease that comes from speaking to friends and colleagues in the publishing and writing industries who think that having one BIPOC author is enough, or that one disabled author is enough, or that having a person of colour give the keynote address at a conference counts in terms of diversity when there is far less diversity to be found in other panels.

It was an unease that flared at a conference I attended recently in Toronto, when an older white man saw fit to stand up in the middle of a panel and “clarify” a point on which he disagreed with one of the panelists. He took up ten minutes of valuable panel time and space. It was time that wasn’t meant for him, and yet it was time that he had no trouble usurping because the world in which he lives has continued to prioritize certain voices over others since Canada as a country began to tell stories—to say nothing of the Indigenous voices and stories that this country has historically ignored.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s an unease that continues to flare for me long after the glow of putting on the FOLD has faded, when I see how even those of us who are trying to do the work in our communities can so often get sidetracked by infighting and ego, by the temptation to cheer and bask in the light that often comes when one is seen to be fighting on the side of what is Right And Good. In this world of virtual celebrity and instant validation in the form of likes and viral tweets, it seems to me that it’s all too easy to conflate activism with the opportunity to make a name for oneself—to view being seen as a Good Person doing Good Things as just as if not more important than doing the work itself.

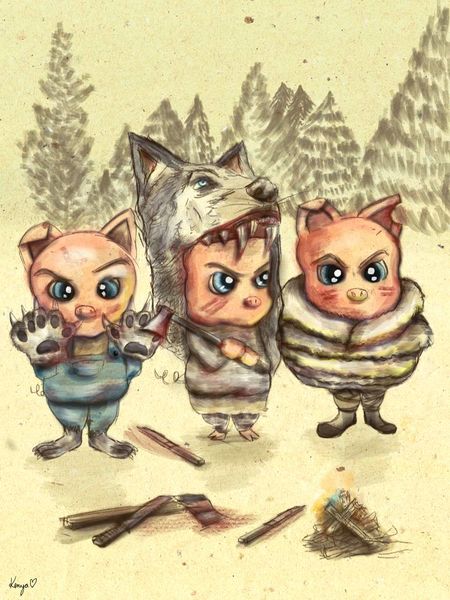

In fairy tales, the world at large hardly ever changes. The Three Little Pigs outsmart the wolf and eat him, and Jack descends triumphant from the beanstalk with his hands filled with gold, but the transformations that happen are individual, never systemic. Jack does not go out into the world and distribute the wealth that he gained from the giant. The Three Little Pigs might kill and eat the wolf, but he is only one wolf, and the world is filled with thousands—what of the countless other pigs out there, left in their own flimsy houses? We don’t think about them. We don’t think about them because these are only stories, yes—but we don’t think about them also because it is easierto imagine the individual triumph as opposed to societal change.

The real world, such as it is, is hardly a fairy tale. But we’ve grown accustomed to cheering when someone beats the odds as opposed to questioning why the odds are stacked against them in the first place. We’ve come to expect the individual triumph even as we pay lip service to the idea that the world needs to change, because more often than not, the collective work required to dismantle the system seems just too damn hard. Dismantling is long work—the stuff of days and years and legislation. It is as much about boring meetings and wrenching frustration as it is about the dopamine-surge of collective activism and that feeling of finally having your voice heard. It is as much about the struggle as it is about the triumph—the long slog, the unglamorous work in the sidelines that doesn’t make for pretty Instagram pictures or handy threads on Twitter. It is equally about the joy of seeing flashes of change as it is about the long, relentless realization that all of this work will take years to fulfill. Joy and heartbreak, hand in hand. Triumph that exists right beside frustration and rage.

When it comes to CanLit, we live in a world that is changing at once instantaneously and at an infinitesimal pace. More voices are being heard now in this country, and different stories are being told. But there’s still such a long way to go, and it’s hard to do the long work and feel like it makes no difference. As a result, it’s often all too easy to look at the world of social media and online rage and see an online platform as the place where change does happen all at once—where one can make a difference right away. But like the man that interrupted that panel at BookSmart, using a system that has inherently been built for his advantage, sometimes I worry that the well-meaning words we exchange in the online sphere—especially those of us who are white, and privileged in ways that marginalized writers often historically have not been—work to entrench privilege just as much as they work to raise awareness. So many of us see Twitter and Facebook and the rise of social media activism as galvanizing forces for change without recognizing that even social media, in many ways, replicates the power structures that continue to slow progress.

As writers, we know that words have power. When I use mine, I try to ask myself these questions:

Am I truly the person who should be saying this, right now?

In speaking, am I speaking over someone else?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In speaking, am I drawing attention to myself (as a Good Person, doing Good Things) and away from those who are better placed to have it?

If I’m unsure about the answers to any of these questions, I try really hard to pause and think about how best to redirect my energy. Often, my energy and my platform is better placed in the service of someone else—as retweets of someone else’s words on Twitter, for example, or in directing attention to an essay or an article that encapsulates an issue in ways that I know I would never be able to do.

It isn’t always about us. Often, with social media, it’s just as much—and in the case of white people, arguably more—about somebody else.

*

Which is not to say that social media and online activism doesn’t have its uses. In the disabled community in particular, social media activism has proven an invaluable tool for people who have found barrier upon barrier when trying to access traditional activist spaces. And in a world that’s growing increasingly isolated and at times difficult to navigate, social media offers a wonderful opportunity for people to connect and make community in ways that feel fresh and exciting and truly capable of galvanizing change.

But activism is a rallying cry—it isn’t a stage. And the fact that social media is a more democratic platform than the media we’ve known in the past doesn’t also mean it’s free from the labyrinthian clutches of privilege. I’d be foolish if I didn’t also recognize that my own cheering, as a disabled white queer woman who can nonetheless pass as more or less able-bodied and straight, carries with it an inherent amount of exposure and power as a seemingly cishet white person. If I am not careful with the way I use my words and my platform, I run the risk of speaking over voices that need to be heard more than mine does.

Several years ago, in my efforts to bring a voice that was marginalized into a space for discussion, I was rightfully called out on my lack of awareness and sympathy toward a particular individual’s situation and unwillingness to speak. I’d had the best of intentions and had honestly thought that I was doing a Good Thing. But I was also in love with the Good Thing I was doing, convinced of my righteous path and thrilled with the knowledge that I would have a part in bringing this voice to more people. It was a love that completely eclipsed my awareness of what this individual wanted for themselves.

To be called out on the inappropriateness of my actions hurt a great deal. It always hurts when you think you’re doing something important and then are shown to be wrong, or cautioned about ways in which you could improve your behaviour. It is difficult to build things when hurt. But this kind of calling-out hurt is necessary—the kind that allows for the cutting back of bad growth so that gardens can flourish. The kind of clean hurt that happens in a community where we look out for one another—where we recognize that the difficult work of rebuilding cannot happen through one person’s actions alone, but is instead supported and made possible through people who help one another triumph.

We owe each other this help, and this uplifting. We owe each other these cheers. But I also think we owe each other accountability—that difficult path of learning how and when to acknowledge the moments when it might be right for us to speak, and the moments when it’s definitely right to move aside and let someone else into the spotlight. That path of learning how to create space for others in a way that doesn’t centre ourselves, and of learning to use our voices in a way that is constructive but also not hurtful.

In this fairy tale, it isn’t the individual triumph that matters, but the way that the community comes together to ensure collective change. And that coming together requires forgiveness—the forgiveness that was given to me after my own fumble, and the forgiveness that I try to extend to others in turn when wrongs are acknowledged and someone truly tries to learn from their actions. We must build room for justice in a way that also builds room to forgive.

All of this is difficult work, and requires constant vigilance. It isn’t easy to navigate the threads of privilege that may make up one’s life, particularly if that privilege also intersects with another kind of marginalization. But I think we owe it to one another to try—to ask ourselves these questions and be honest about our answers and our responsibilities, as well as be honest about how we may or may not be ready to forgive those who make mistakes but own up to them and seem committed to change.

Let’s write another kind of story in the world of CanLit—one that’s joyous but also fierce, filled with an empathy that’s deep and boundless but also doesn’t let us off the hook. Let’s stop fighting to be seen as saying and doing the right things and just do the right things, no retweets or Twitter likes required. Do something good, and don’t expect validation for it. Do something good, and don’t expect recognition for it—particularly if you come from a place of privilege.

The world that we’re building is not about the individual hero. It’s about all of us. This is the world that we need to celebrate, and the growth that we need to help flourish.

This, in the end, is what we owe to one another.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Amanda Leduc is a disabled author with cerebral palsy whose stories and essays have appeared in publications across Canada, the US, the UK, and Australia. Her first novel, THE MIRACLES OF ORDINARY MEN, was published in 2013 by Toronto's ECW Press, and her new novel, THE CENTAUR’S WIFE, is forthcoming with Random House Canada. She lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where she serves as the Communications and Development Coordinator for the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD), Canada’s first festival for diverse authors and stories.