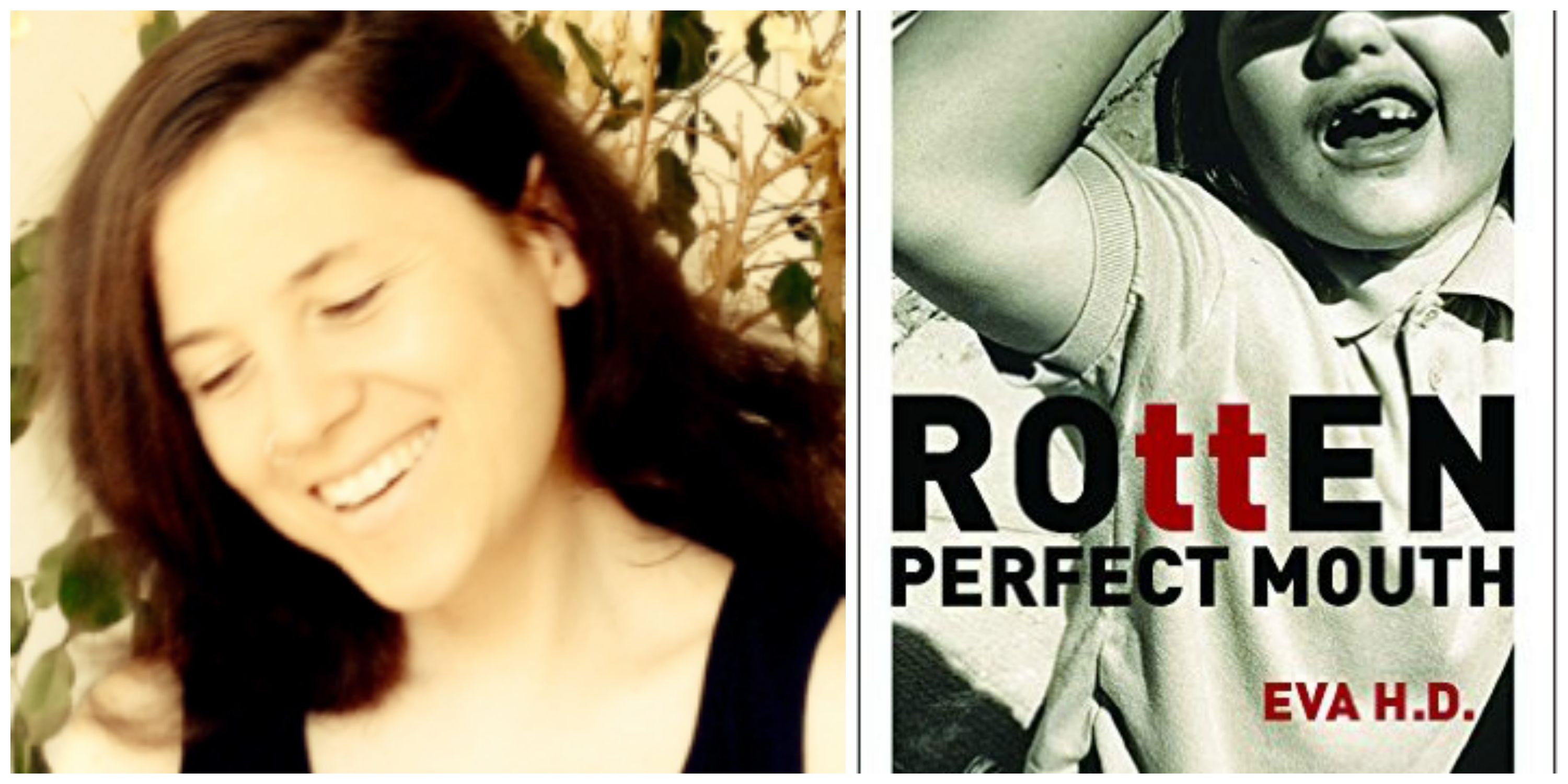

“You can't write fiction on a napkin,” an Interview with Eva H.D.

By James Lindsay

There is a strand of literature that aligns itself closer to the blue collar, working class values of general communication and accessible story telling than the “high-brow,” all encompassing grand narratives that academia and publishing often celebrate. Much like the promise of punk (it can be yours too, if you want it), this strand preaches an intellectual accessibility, a literature both confessional and class conscious; stories that are unabashedly intimate and set in a time and space that the reader can personally relate to. If this reader appears as a concrete image in the mind of the writer when composing, it is because she already knows them, has lived alongside them. (Think Charles Bukowski, Al Purdy or Lucia Berlin.) And the case could be made that the division between these strands is felt strongest in poetry, where the esoteric can earn a higher cultural capital than the accessible. All this to say that this is the strand Eva H.D.’s poetry inhabits. The familiarity these poems invoke is instantly recognizable to anyone who has lived in a city, especially Toronto (though Eva H.D. may disagree with this), and has shared in the small pleasures that come with it (of warm bike rides on August nights, long park bench conversations about life in plain view of hundreds, the sudden awareness of how much life, how many stories you orbit at any time), and, in her more recent work, to the traveler who willingly gets lost in order to have something to explore, and to the ones left behind, who live day in and day out with the tint of longing, waiting for someone to return.

James Lindsay:

Your first collection, Rotten Perfect Mouth, while being very Toronto-centric, ends with a travel poem, "Jerusalem Morning." Your most recent collection, Shiner, contains more moving around between places. Was there a bout of traveling between books or was that just where your writing went?

Eva HD:

I dunno - I'd guess that probably has more to do with the way that Denis at Mansfield picked them.

Although, since you mention it, I suppose it's probably fair to conjecture that I was in love with Toronto when I wrote the things in Rotten Perfect Mouth, and I am not in love with it, any more.

Lindsay:

How did you fall out of love with Toronto? And what was it you loved about the city in the first place?

Eva HD:

It washed its face with Javex in a bid to become some cosmo-sipping teenager's teevee wetdream about an imaginary New York. What I loved about it before was its as-is-ness; I loved it as is.

Lindsay:

Are there any parts of the city you think still cling to the pre-makeover, original warts?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Eva HD:

Ha! Yeah, probably. No one died and made me King of Olde Toronto, mind you. Just because I'm complaining like an old man on a porch, doesn't make me right.

Lindsay:

Of course not. But as some one who has spent most of his life here, I, too, have watch the city change in ways I'm not always a fan of. I was just curious which parts still represent your favourite side of the city.

Eva HD:

The Mount Dennis neighbourhood reminds me a lot of what this city used to feel like. Some parts of Queen St. E, too.

I guess I might add to that: any cafe or bar or park where English is not the primary language being spoken.

Lindsay:

Was that part of the allure of travel for you? The feeling of being an outsider by not understanding the language?

Eva HD:

No.

Lindsay:

So what do you like about being in a place where "English is not the primary language being spoken"?

Eva HD:

I dunno. I suppose I was just trying to come up with a feature of the city that reminds me of what it was once like. People are, of course, welcome to speak English whenever they want to. But when I think of how the city has changed, in many neighbourhoods, it seems to be that English has suddenly replaced non-English in the homes and on the streets and in the cafes and bars and other local businesses.

Lindsay:

I was interested in that because your poems often feel like short scenes with characters and dialogue, and I was curious where they come from. Are these people you know or just people you recognize from the parks and cafes?

Eva HD:

Not sure. I guess it probably depends.

Lindsay:

Alight then. Let's put it like this, what kinds of things make you want to write? And why write poems and not, say, fiction?

Eva HD:

Pretty much anything could make me want to write; though I imagine that probably applies to everyone and is maybe not that helpful; but otherwise, I don't really know.

I would say that the main reason I would write poetry instead of fiction is temporal-spatial constraint; you can't (I can't) write fiction on a napkin.

I think that's probably the main difference, but I could be wrong. Maybe I should have looked up a definition of 'poetry' before attempting to answer that correctly.

Lindsay:

You talk about poetry from a very personal perspective. Was there a moment you connected with a particular poet or poem that made you want to write, or do you write poetry just because you want to and it takes up little space? Do you even like other poetry?

Eva HD:

That is a good question.

I noticed some years ago that I tend to like poetry that contains bears. But then, it's not a hard-and-fast rule, because I also like poetry that doesn't have any bears in it. There's a poem I'm crazy about by James Wright that doesn't feature a single bear. But it is about American football, which, arguably, is a somewhat bearish pastime. Incidentally, the NFL's Chicago Bears just lost their first game of the season this Sunday, which is no doubt some sort of instance of poetic justice, somehow.

Lindsay:

So do you read write poetry instinctively, without over thinking it? Or are these answers a way of avoiding talking about poetry?

Eva HD:

Yes and no. In order, I mean - like, yes, that's probably quite true for the first question, and no for the second.

I really do have a weakness for bear-themed poetry, because it's the best. And also the Bears, although they are quite demonstrably not the best.

Here is a nice example of a bear poem. http://www.lyrikline.org/en/poems/notes-toward-lexicon-language-bear-4481#.V-kQwDKZOGQ

Lindsay:

I love Paul Vermeersch's animal poems. For me, it's dog poems. Like this one by Timothy Donnolly. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/06/30/malamute

Can we converse a bit about why bears? And what makes "Notes Toward a Lexicon of the Language of the Bear" a good bear-poem?

Eva HD:

I think bears do well in literature. Maybe because they spend so much time sleeping?

I'm not sure what makes it a good bear-poem objectively, but I like it because a) I think I understand it; and b) it sounds nice. And 'This side of the mountain is mine' is probably a fun thing to say at any time, bears or a lack thereof notwithstanding.

Lindsay:

So, unless you have anything else to add, let's wrap it up here.

Eva HD:

Sure thing, boss.

And also, why do you go in for dog poems?

Lindsay:

I like dogs in poems (and dogs in general) because I think they're tragic. All breeds of dogs have 99% wolf DNA in them. Over thousands of years humans have bred them to look the way they do so they could perform tasks for us like hunting, herding, sled pulling and security. Even a pug was bred to have a specific working purpose. We took advantage of their pack mentality and their need to please so they could work for us with only companionship as a reward. Of course now most dogs only exist as pets, but they still have this working instinct. Humans have made these weird little animals that just want to make us happy, and in exchange we over breed them and leave them alone all day. But I also like dogs because they can represent the best qualities I see in people: loyalty, empathy, tolerance.

Why do you think you like bears in poems?

Eva HD:

"Humans have made these weird little animals that just want to make us happy, and in exchange we over breed them and leave them alone all day. " Too true.

I don't really know why I like bears in poems; I wish I had something that specific to say, but it seems to be more of just a coincidence. Literary bears, like the ones in The Hotel New Hampshire [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hotel_New_Hampshire], for example, have always just appealed to me. I certainly didn't know that pugs were bred for work. What work was that? Wriggling?

Lindsay:

Ha!

Pugs were sheep hearing dogs from China. Somehow.

Here's a helpful graph from National Geographic that breaks down the breeds: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/02/build-a-dog/dog-families-graphic

Eva HD:

I now have added 'watch a pug herd sheep' to my life goals.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.