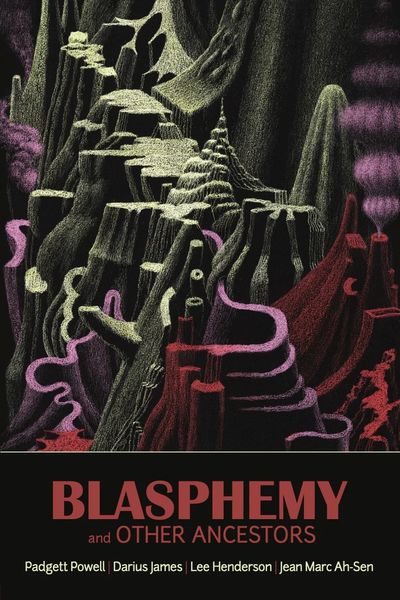

A Discussion of Blasphemy and Other Ancestors: 4 Novellas by Padgett Powell, Darius James, Lee Henderson, & Jean Marc Ah-Sen

"It's the fate that awaits us all," says Jean Marc Ah-Sen of the four novellas in Blasphemy and Other Ancestors (Gordon Hill Press), written by him, Padgett Powell, Darius James, and Lee Henderson, explaining how each one of these innovative, genre-bending tales is, in its own way, "about becoming peripheral to the world around you and looking to the past for meaning".

Henderson adds, with a bit of dark humour, "a grim conviction, that’s what I think connects the four novellas". This conviction is apparent throughout the collection — a conviction that storytelling can be stretched and experimented with, that existence can be explored thoughtfully, hilariously, and heartbreakingly, in the demanding, and often unappreciated, short form of the novella.

We're excited to speak with all four authors of Blasphemy today as part of our series exploring how anthologies come together.

Arguably four of Canada's most fascinating literary innovators, Ah-Sen, Henderson, James, and Powell tell us about the characters they've created, from a questionable academic to a beloved aunt, the literary value of air conditioning and coffee, and why this was the right time to bring this incredible tales together in one volume, a book that author Michael LaPointe called "four excursions to the outer limits of perception."

Open Book:

Tell us about the new book and how you became involved with it.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen:

During the pandemic, I had two projects I was trying to get off the ground: a male groupie novel called Kilworthy Tanner, and a multi-author pocket book series I was calling “Insolite Books.” The latter was supposed to be a Canadian version of Hanuman Books. The line-up kept morphing, and eventually the stories got bundled into the anthology collections Disintegration In Four Parts (Coach House Books), Blasphemy and Other Ancestors (Gordon Hill Press), Dead Writers (Invisible Publishing), and a couple of other books that haven't been announced.

Blasphemy contains novellas about becoming peripheral to the world around you and looking to the past for meaning—every breath becomes an act of blasphemous resignation, I suppose. It's the fate that awaits us all.

Open Book:

What drew you, personally, to this subject matter, and why was this the right time to gather the pieces in book form?

Padgett Powell:

I saw a nicely done piece outing a revered Southern gentleman writer who called his university-supplied amanuensis “Beloved.” Irresistible for irreverence. I operate on the interface between taking the South seriously or making fun of it. It’s always the right time.

Darius James:

I missed my aunt. She had walked on water, like her buddy Jesus, and entered the crystal castle, passing herself along the way. This was many years before, in my mid-teens, sequestered away at boarding school. Now, thirty-five years later, in the city of Berlin, I missed her plate of sputtering grease bubbles. My year in boarding school had been a rough one. My great aunt had not only faded from my life, but my mother had shrivelled into a husk of dried lifeless flesh.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Lee Henderson:

I wanted to tell a bit of a caper about a Jew haunted by the Second World War and all that was lost. I was thinking about the slow-cooked stew called cholent that Jews made for shabbat in the shtetls of old Europe. I was thinking of the lost world of 1970s filmmaking and I wondered if there was a way to draw a line between the three.

JMA:

I had this idea for a character named Acton Quennell, an anti-Buddha type. He can recall his past lives, but this awareness turns him into a voluptuary instead of a God. My story’s meant to read like a bad joke taken a little too far, like Terry Southern’s The Magic Christian or Jane Collier’s An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting.

Open Book:

What do you hope readers will take away from these pieces, after having read them? Is there a question you set out to address or delve into through these works?

PP:

I trust the reader survives thinking she’s seen some good writing.

DJ:

There is a belief in Vodou that says if you want to speak to the departed, or denizens of the Invisible, you simply talk to them. I observed this in New Orleans. Manbo Sallie-Ann Glassman hosted a houngan in her home for a time by the name of Edgar. He was Haitian and her Papa. I was there preparing for an upcoming film shoot. As I came in and out of Sallie's hounfor, or sacred space, busying myself in the backyard, I watched Edgar sitting in a folding chair under the branches of a weeping willow, whispering to budded vines swaying in the breeze. “Spirits,” I thought. He was talking to the Invisibles.

I missed my aunt and her fried breakfast. I sat down at my desk in Berlin and wrote wildly, without specific aim. It was a surrealist act, a game for the subconscious—what the Dadaists called “automatic writing”. Then I heard a voice, as I wrote, in a cloud of gibberish. I continued writing and gradually recognized the voice. It was my aunt, speaking in fractured dialect, sounding like Joel Chandler Harris sipping Robert Johnson's poisoned moonshine. If we could speak to the Invisibles according to Vodoun belief, did not the Invisibles converse with us in kind? This was possession. Voudo. I was the voice of my aunt. I was her horse.

LH:

Jews of the 21st century live inside a weird postmodern narrative, a non-narrative, an anti-narrative, an absurd moment of moral opposites, a crisis of conscience rooted in our collective dream, our own collective aspiration, a collective fear invoked through collective nightmare. Our collective face is filled with asymmetries. But, I wonder, what if there is still, at the least, humour?

JMA:

I am still trying to produce a work of liminality that I can be happy with; something approaching a Philip K. Dick story possibly. My novella could ostensibly be about a man’s consciousness transcending time and space, or maybe of achieving Buddhist jatismara, but on a much simpler level, it’s about a wastrel experiencing a very serious mental health crisis.

Open Book:

What defines a great collection or anthology, in your opinion? Were there anthologies you looked to for inspiration?

PP:

Good handful of good pieces, without undue agenda-izing.

LH:

I loved Andre Breton’s Anthology of Black Humour. That was probably the most important anthology for me as I began my writing life, and I turned to it again when I began work on this project. What I loved about that anthology is the radical subversion of form. A grim conviction, that’s what I think connects the four novellas in our book.

JMA:

For me, it’s Cyril Ray’s 16-volume food and wine anthology, The Compleat Imbiber. Its breadth is almost impenetrable and I admire any literary project that has the air of a doomed endeavour.

Open Book:

What do you need when you’re writing and editing – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

PP:

More and more, life is a function of one thing: air-conditioning. The basics has become the basic. I live in Florida under a Trumpist who feels he is too short if his feet are allowed to bottom out in his boots. He’s on tippy toes up in the shaft of the boot. As Coleridge put it, there are more things invisible than visible in our world. Where is the Laudanum now that we need it?

LH:

I start new drafts in two separate spaces: on the computer and on a yellow legal pad. I use the legal pad for really rough writing, uncensored sketches, and trying out potential stuff that may or may not work. I use the computer to work on voice. I start writing voice on the computer. Eventually voice begins to develop into narrative and I can start to plug in some of the stuff I’d been working at on the yellow legal pad. I use a mechanical pencil that was once my grandfather’s. I listen to music while I write. I drink a lot of coffee. I’ll smoke and drink coffee and eat snacks and write all night if I can.

JMA:

Have spleen, will travel.

_________________________________________________________

Jean Marc Ah-Sen is the author of Grand Menteur, In the Beggarly Style of Imitation, and the forthcoming Kilworthy Tanner. His work has appeared in Literary Hub, The Walrus, The Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, Maclean’s, Hazlitt, The Comics Journal, and elsewhere. The National Post has hailed his writing as an “inventive escape from the conventional.”

Lee Henderson is the author of four books, including two novels, The Man Game and The Road Narrows As You Go, and a short story collection, The Broken Record Technique, and most recently a novella in the collaborative book Disintegration in Four Parts. He teaches creative writing at the University of Victoria.

Darius James (aka Dr. Snakeskin, born 1954) is an African-American author and performance artist. He is the author of That's Blaxploitation: Roots of the Baadasssss 'Tude (Rated X by an All-Whyte Jury), an unorthodox, semi-autobiographical history of the blaxploitation film genre, and Negrophobia: An Urban Parable, a satirical novel written in screenplay form. His work is influenced by the Voodoo religion. James lives in Hamden, Connecticut.

Padgett Powell is the author of six novels, three story collections, and one non-fiction book. He has retired from a long career of schoolmarming which was necessary to pay for things to live.