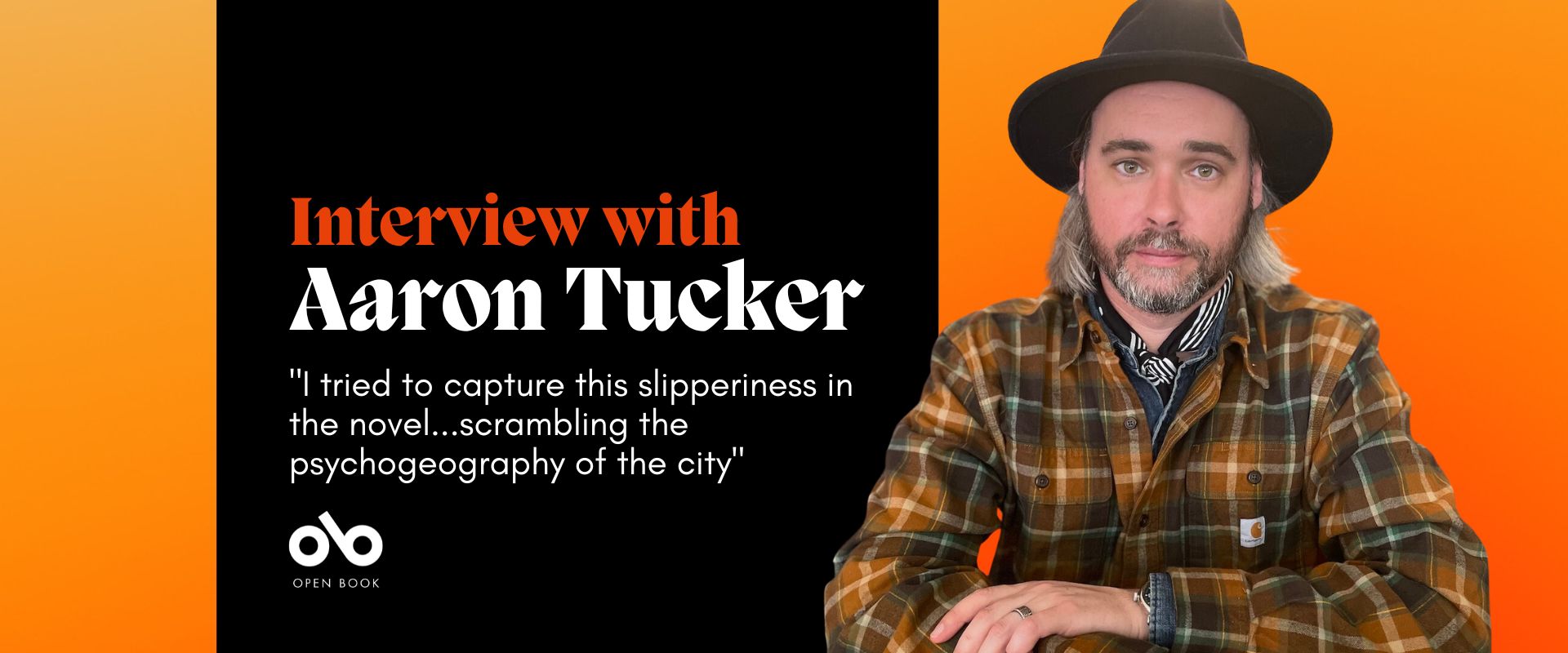

Aaron Tucker Creates an Updated, Nuanced Twist on the Classic Western in His Gripping New Novel

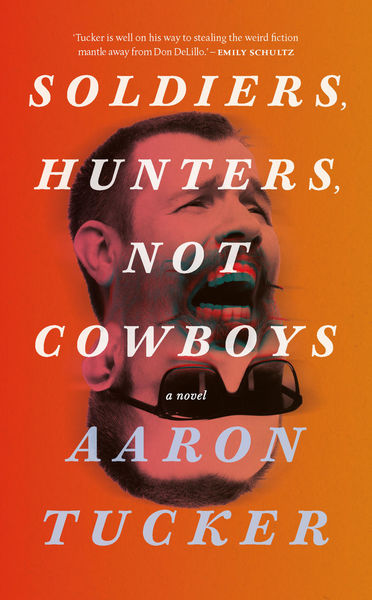

Aaron Tucker's novel Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys (Coach House Books) is a startling and brilliant blend of a book, beginning as a play-like conversation between two ex-partners in which Melanie, a woman obsessed with the 1956 John Wayne film The Searchers, recounts the movie's plot. Tucker creates palpable, visceral tension as the evening falls apart due to the unnamed ex-boyfriend's drunken belligerence.

This Carver-like set piece would be enough to coast on for many, but Tucker doesn't rest on his laurels. Instead, the book takes an unexpected turn: two days after The Searchers conversation, a strange, catastrophic event throws Toronto into chaos. The sobered-up protagonist sets out to find Melanie, much like Wayne's character in the film searches for his niece, not realizing the cinematic levels of violence and chaos he's about to encounter.

Tucker's exploration of violence, masculinity, and storytelling is layered, wise, and timely. Examining the themes and tropes—as well as the racism and misogyny—of the iconic movie at its core, Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys is both propulsive and impressive, and we're speaking with Tucker about it today as part of our Long Story interview series for novelists.

He tells us how despite its Toronto backdrop "the (unseen) setting for the entire novel is the desert of The Searchers," shares the appropriately themed video game that became part of his writing process, and details the thoughtful process behind his epigraph selections.

Open Book:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

Aaron Tucker:

I had just moved to my current apartment in St. James Town, across from Allan Gardens. While I didn’t really understand what I was writing, the novel began with me walking the neighbourhood for about an hour, taking photos, then going home and sort of free writing about what I had seen. I tried to retain that step-by-step detail as much as possible in the second half of the book, because I find my neighbourhood beautiful, and at the heart of Toronto’s struggles with affordable housing, constant condo construction, and the street-level struggles of how people live in the city.

By contrast, the apartment that remains largely un-described in the first half of the book, is, in my mind, close to the first apartment I lived in when I first moved to the city, in the Dupont-Ossington area, nearly twenty years ago now. I lived in the upstairs of a one of the classic post-WWII Toronto homes, cozy with big bay windows and lots of light, a kitchen window that looks out over the back yard. Melanie’s apartment is meant to be welcoming, despite the protagonist’s semi-intrusion into it.

But I do think the (unseen) setting for the entire novel is the desert of The Searchers, which eventually maps itself onto the second half of the book. The movie’s story takes place in Texas, but was filmed in Monument Valley in Arizona, on movie lots in California, and even in Alberta. The movie is “set” in one place, Texas, but covers so many imaginaries by blending itself with so many actual geographical locales. I similarly tried to capture this slipperiness in the novel, with the movie sliding into the “real” streets of Toronto, in turn scrambling the psychogeography of the city.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

AT:

I didn’t really have an ending to the novel until the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020. I had a general direction I thought I would go, based on The Searchers, and had even mentally written the last line that would eventually end the novel. But, until the pandemic, I wasn’t sure how far across the city the protagonist would make it. Then I began walking through the neighbourhood in those early weeks of semi-lockdowns, as a break from obsessively monitoring the infection and death statistics. I took photos as I did when I started the novel, documenting, and it became apparent that the novel had to stop at that moment, that the protagonist could go no further. The airborne event and the cloud that literally looms over the second half of the novel took on a totally new resonance during Covid-19, and, and with those echoes, I found it made a lot of sense to end the stereotypic hero’s journey abruptly and internally, in his memories and hallucinations.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

AT:

I would frame it as a question: What would the contemporary version of John Wayne look and act like?

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

AT:

I did some reading on the abduction of Cynthia Ann Parker in mid-19th century Texas that would be the skeleton for the narrative of The Searchers, then some research on the writing of the book, and then the making of the film. However, I didn’t want to read a lot of criticism about The Searchers because neither characters are film scholars. More usefully, I watched a lot of Westerns, as many from the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s as possible, including the terrific Budd Boetticher films, classics like the 1957 3:10 to Yuma and 1943 The Ox-Box Incident, and other Wayne films like Stagecoach, The Shootist, and True Grit.

Just as important to the film, however, were more contemporary takes on the Western, films I was hoping to channel is some way into the novel. I’m thinking specifically of The Rider (directed by Chloé Zhao), First Cow and Meek’s Cutoff (both directed by Kelly Reichardt; I take one of the epigraphs from Meek’s Cutoff) and The Harder They Fall (directed by Jeymes Samuel). I found it essential to watch these takes on how the Western lives and breathes in the current space in culture, how the films are both intimate and epic, and how they resist and embrace the genre. The Rider is such a gorgeous and heart-breaking small film, while The Harder They Fall is one of the coolest, most stylish movies I have seen in the last five years, and re-imagines the genre of the Western as a totally Black world.

It’s also worth mentioning, especially given the confinement of the pandemic, how much Red Dead Redemption 2 I played while I was editing; I liked the game’s story enough, but mostly I enjoyed getting on my horse and exploring, picking plants and hunting in the massively expansive game space.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

AT:

I deliberately chose Canadian authors that were influential to me, namely Thomas King, Marian Engel, and Timothy Findley. During writing, I often thought about Engel’s The Honeyman Festival, a Mrs. Dalloway-style recounting of a housewife’s day that is interwoven with her memories of her affair with the Honeyman, a former Western movie star. Findley’s Headhunter seemed very appropriately given how his Colonel Kurtz springs from Heart of Darkness into Toronto, while the city is being tormented by some sort of airborne event. And King’s work aims itself directly at the figure of John Wayne and literally kills him, an act of great catharsis and revision.

The book I wished I was able to overtly add was Richard Wagamese’s Medicine Walk. It is a book I read and re-read, then re-read again, in part because it is incredibly gorgeous and moving, in part because it reminds me of where I grew up in the interior of British Columbia, but also because of its interweaving of the Eldon and Franklin Starlight. Naming the two parts of my novel “Fathers” and “Sons” was a nod to the book.

OB:

Did you celebrate finishing your final draft or any other milestones during the writing process? If so, how?

AT:

Alongside editing and the final stages of production of the novel, I was finishing my Ph.D. in Cinema and Media Arts at York University. My graduate work and this novel were brought together, even though I worked fairly hard to keep them separate. But all the care and space I was given at York by faculty and friends was essential to this book. In the end, I think it’s fitting that two weeks after the publication date for this novel, I convocated, walking across the stage to get my diploma.

________________________________________________

Aaron Tucker is the author of three books of poems as well as the novel Y: Oppenheimer, Horseman of Los Alamos (Coach House Books) which was translated by Rachel Martinez into French as Oppenheimer (La Peuplade) in the summer of 2020. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Cinema and Media Studies Department at York University where he is an Elia Scholar, a VISTA Doctoral Scholar and a 2020 Joseph-Armand BombardierDoctoral Fellow.