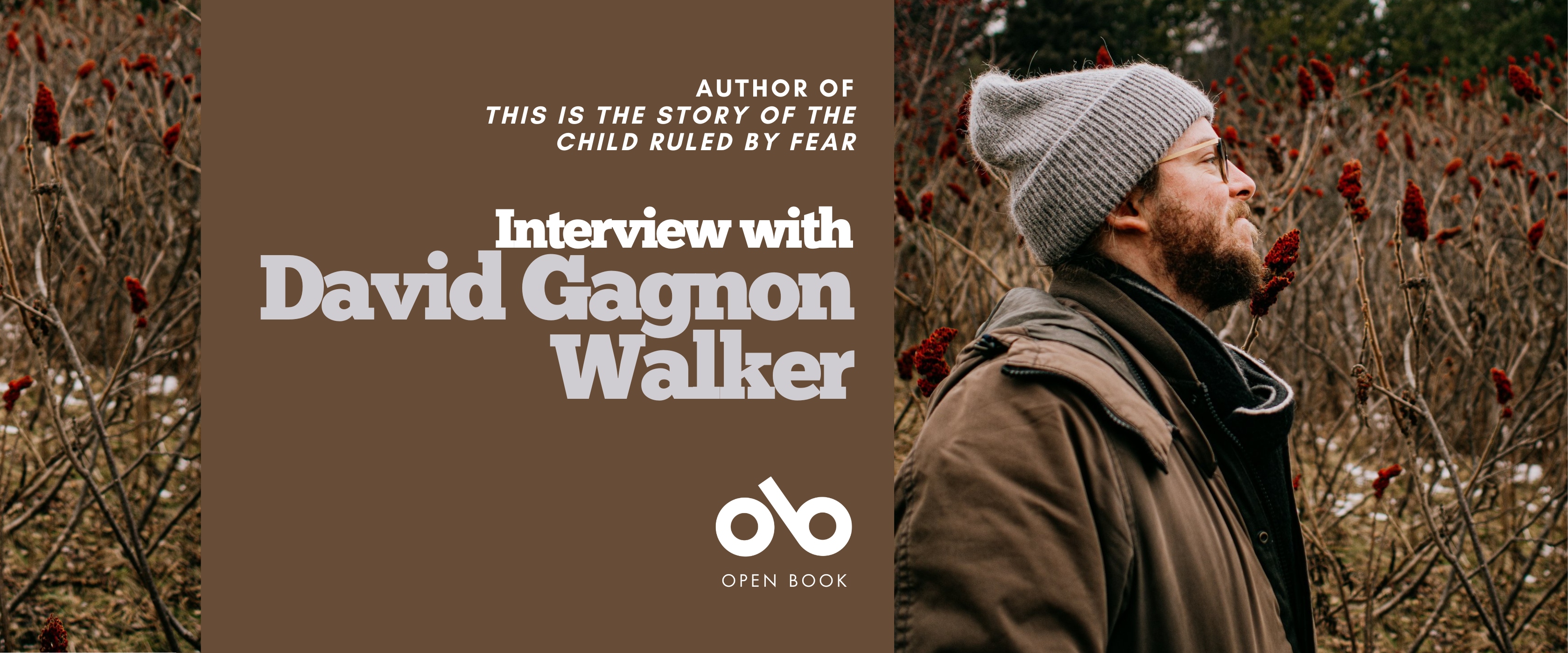

Acclaimed Artist David Gagnon Walker Guides the Audience Through Fear and Anxiety in an Immersive, Interactive Stage Play

It has been said that, if David Gagnon Walker's name appears on a theatre playbill, the audience should prepare themselves for the unexpected. The playwright has created some of the most interesting and inventive stage work to come out in Canada this decade, and continues to evolve and produce spellbinding performances.

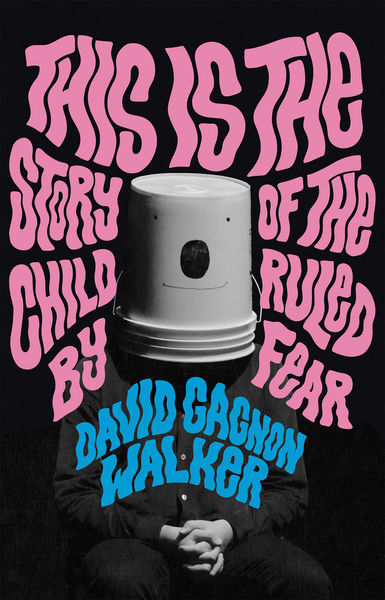

His latest work, This is the Story of the Child Ruled by Fear (Playwrights Canada Press), has been touring since 2021, and has been captured in the recently released book of the same title. It is an interactive work where the performer and a gathering of friends and strangers read out loud. The play winds through real and imaginary lands, epochs that have come and gone, and true or fictional representations of the various forms of collapse around us.

The experience is a cathartic coming together, where the collective group tackles these moments together instead of facing them alone, which is an act of beauty in itself. The author guides us through the process deftly, allowing us to confront fear, anxiety, and the ills of our lives and come through it all with grace.

Read more about this riveting work in our Behind the Curtain Playwright interview with the author, right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

How did this play first come to life for you? Do you remember the first bit of writing you did for it?

David Gagnon Walker:

This Is the Story of the Child Ruled by Fear works like this: seven audience volunteers sit on stage with me and read the play out loud, with the rest of the audience acting as a Greek chorus. The story we tell together is a dark, surreal fable about an anxious character named the Child Ruled by Fear, who lives in a magical world full of gods and monster, and watches a civilization build itself up and then fall in a natural disaster.

The mythical story and the formal convention of the audience reading out loud came to me separately. The Child Ruled by Fear stuff started as a series of weird little texts I was scribbling in a notebook without knowing exactly why. The material didn't really feel like drama, poetry, fiction, or anything else "identifiable" or "useful", but I kept writing it because it felt good.

Meanwhile, I had been experimenting for years with reading in performance. The first read-through of a new play is my favourite part of the theatre process, and as an audience member, I often prefer readings to full productions: to me, they are when plays feel most surprising and alive. I wanted to capture that magic in a repeatable show. Eventually I decided the solution was a show where the audience reads the play. I knew this would be nerve-wracking for some folks, so I figured the show should probably be about nervousness. When I realized I had already been scribbling a fun story about nervousness in a notebook, everything came together.

OB:

What drew you to the setting of your play and how did you go about creating it?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

DGW:

The Child Ruled by Fear lives in a strange, psychedelic world. Writing about it, I was thinking a lot about the idea of inner landscapes. I think we all have an imaginary world inside us, the terrain of which is shaped by our experiences, personalities, dreams, and fears. The epigraph to this play is a quote from Agnès Varda's beautiful film The Beaches of Agnès: "If we looked inside people, we would find landscapes."

I was inspired by many films and books where the personal and the fantastical meet in idiosyncratic ways. Agnès Varda's amazing filmography, Guy Maddin's My Winnipeg, Werner Herzog and Les Blank's documentaries, Renee Gladman's incredible series of novels about the imaginary city of Ravicka, most of what Anne Carson does... the list goes on.

My own inner landscape has been shaped by the two places I grew up in and still feel I belong to. I was born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta, and spent summers in my mom's hometown of Chicoutimi, Québec (in the Saguenay region, which I think is one of the most picturesque places on Earth, and which few non-Quebeckers seems to know about). Both these places are northern, rugged, far from other cities, freezing cold in the winter, and full of natural beauty. In 1996, part of Chicoutimi was destroyed in a devastating flood when a dam overflowed after record rainfall. Watching the flood from my uncle's minivan parked on a bridge is one of my first memories, and informed this play in very concrete and more abstract ways.

Edmonton and Chicoutimi aren't really thought of as cultural hubs, and artists I know from both these places tend to share a delightful suspicion of "the industry". I think this helps explain the outsider attitude I've always taken towards mainstream Canadian art practice, and why I insist on doing strange things like making a play the audience reads.

OB:

Which of your characters do you feel most connected to in this work, and why?

DGW:

I pretty much am the Child Ruled by Fear. In many ways this project is about my own mental health (and periodic lack thereof). I live with a lot of anxiety and despair. I often feel like the only person who does, but I know that isn't true. We are legion, especially in these distressing times. This show tries to create an opportunity for the audience and I to acknowledge these (often isolating) feelings together in a fun and cathartic way. Having that experience with audiences across Canada has been the most gratifying thing about touring the project.

OB:

In your opinion, how does one go about writing great and memorable characters for the stage?

DGW:

Honestly, I'm not sure how much I think about character. I see characters as clusters of sentences, and sentences as series of events. A play is a list of things that happen on stage, and characters are what we call it when actors do those things.

So, I guess my view is that good stage characters say and do surprising and delightful things, with some kind of underlying logic or coherence. Real people say and do surprising and delightful things all the time. Paying close attention to them is a good place to start.

OB:

Are there other playwrights that you’ve been inspired by? What qualities in their work are you most drawn to?

DGW:

God yes. My whole life is the product of a long list of inspirations.

Reading Samuel Beckett as a teenager showed me that the way I was seeing the world wasn't totally unprecedented or insane.

Meeting Elena Eli Belyea and Geoffrey Simon Brown in my early twenties showed me it was possible to make your own plays with your own friends, and that you could dedicate your life to that if you got good enough.

Jill Connell, Evan Webber, Olivier Choinière, and Marcus Youssef gave me an expanded sense of what playwriting can be, and a tradition to aspire to be a part of.

Gabrielle Chapdelaine and Mishka Lavigne, the francophone writers I've had the pleasure of translating over the last few years, showed me a whole other world of playwriting I relate to with a whole other part of my brain.

Much of my favourite theatre is made by people who don't identity as playwrights. STO Union, Theatre Replacement, PME-ART, xosecret, Jaha Koo, and Forced Entertainment have all blown my mind and changed my art. So have many contemporary dance artists. I love any performance that feels engaged with what's actually happening in this room right now. The shows I love most seem to find a sweet spot between that realist question and an expansive imaginary world.

My work feels depressingly inadequate when I compare it to any single one of these inspirations. But, I can see a unique niche I've carved out at the intersection of all of them, and even sometimes feel proud of it. I think that's what people call "finding your voice."

OB:

Do you feel your work has changed in any way through your writing life and career? If so, how?

DGW:

I think I'm getting less cocky, more confused, less clever, and more honest. I'm less interested in proving or explaining myself, and more interested in what can't be explained. I'm also writing more slowly, which feels related. And I'm swearing less!

OB:

How would you define the role of theatre in society?

We go to theatre to be in rooms where we don't know what's going to happen. Everything now feels predetermined. The money and power hungry have strapped us all onto a slow train to hell, and our lives and discourse are being enshittified in mind-numbingly predictable ways to make a handful of rich people richer. We've been trained to perform certainty and authority everywhere all the time, for the benefit of tech companies that profit off our desire to be heard.

In this context, we need places we can go to be surprised. We need rooms where we can have feelings in public, and witness other people having feelings in public, without worrying something frightening and irrevocable will happen to us if we do. We need spaces for uncertainty, mystery, stillness, and grace. Theatre can provide these spaces. It very rarely does. (It's very hard to do.) But I know it can happen, because I've had those experiences. And having had them, I feel committed to a life that makes more of them possible.

_______________________________________

David Gagnon Walker is a writer, performer, and translator born in Edmonton and based in Toronto. His work has been performed and developed in cities across Canada, and through residencies in Sweden, Finland, France, Australia, and the USA. His awards include the Playwrights Guild of Canada RBC Emerging Playwright Award for The Big Ship, first prize in the Wildfire National Playwriting Competition for Pink Moon, and the Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal Cole Foundation Mentorship for Emerging Translators. Other plays include Premium Content (Major Matt Mason Collective/High Performance Rodeo), The Last Children (Curtain Razors), and the English translation of Gabrielle Chapdelaine's The Retreat (Imago Theatre). David is Artistic Producer of Strange Victory Performance, a collaboration with composer and video designer Tori Morrison, through which he has been touring experimental and interactive performance projects since 2020. He holds an M.A. in Performance Studies from the University of Toronto and is a graduate of the playwriting program at the National Theatre School of Canada.