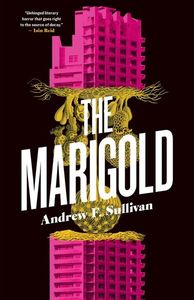

Andrew F. Sullivan Explores a Literally Toxic Future Toronto in His Crackling New Horror Novel, The Marigold

One could arguably already describe Toronto's housing market as dystopian, but in Andrew F. Sullivan's wickedly dark new novel The Marigold (ECW Press), Sullivan takes our metaphorical horror-scape and makes it literal, as an unstoppable toxic sludge begins to seep from a gleaming new luxury condo building, threatening everyone in the city.

Set in a near-future version of Toronto, the building at the centre of Sullivan's story is the titular Marigold, built by Stanley Marigold, the failed scion of a millionaire developer. It is Marigold's version of a deal with the devil, entered into because of his desperation to maintain his wealth and power, that plunges Toronto into chaos as the toxic mold spreads, fraying the fabric of the city's infrastructure.

With a cast of characters that include a health inspector, a ride share driver, and a tween intent on rescuing a friend captured by a mysterious horror, The Marigold is a propulsive, jagged, and often even darkly funny exploration of the climate crisis, urban greed, and the spiritual cost of rampant inequality. Setting community, hope, and a little downtown ingenuity against corruption and a truly unique monster, The Marigold is one of the must-read novels out this season.

We're excited to speak with Andrew, whose previous work has earned him accolades including a nomination for the ReLit Award, about it today as part of our Long Story series for novelists. He tells us about the Toronto-set horror stories that came before and inspired him while writing The Marigold, how his research into Toronto's failed Trump Tower debacle taught him that "it’s hard to stop a disaster once it gets moving", and why he dedicated his book to his wife, author Amy Jones, saying "The Marigold does not exist without Amy."

Open Book:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

Andrew F. Sullivan:

I lived in Toronto for over a decade and grew up under its influence as far as the GO line stretches. The CN Tower does its best to express dominion over all who can see it; it interpolates every being under its stoic gaze. Toronto is a metropolis, the core of Canada, but also a confused place, one that often refuses to admit it’s a real city and pretends it can just exist as a series of neighbourhoods. It’s slightly unexamined as a sight of horror, despite its freezing concrete impression in winter and soupy, oozing nights in summer, the raccoons feasting through every season on the busted trash cans that have become the city’s trademark, festooned with poop bags.

With my horror novel The Marigold, I am following in the footsteps of people who came before me like David Cronenberg, who used the city as his canvas for movies like Crash, Dead Ringers, Videodrome, and The Brood, or Timothy Findley who brought the fantastical and the terrifying to the city in his novel Headhunter, where Colonel Kurtz has emerged from page 92 of Heart of Darkness in Toronto Reference Library to take command of the Parkin Psychiatric Institute, a stand-in for the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health on College Street. And more recently, David Demchuk’s novel Red-X, a deep and horrifying examination of Toronto’s bloody, prejudiced history made into vivid, tormented flesh. Toronto is big enough to tell all these stories and more. It deserves to exist on the page, even when the places we chronicle are disappearing.

I wanted to write about the place that had kept me in its orbit for so many years, the place that I had lived in for over a decade, from Bathurst & Finch to Cabbagetown to Morningside & Lawrence. I wanted to write about a place that was decaying in plain sight, a place still worshipping the car, a place that had barely prepared for the future of our climate catastrophe. And Toronto was the perfect place for that. A city that claims to be world class and yet shudders when you suggest tearing down the Gardiner Expressway. A city in a perpetual state of remaking itself in someone else’s image. A city that pretends it has already achieved greatness.

OB:

If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

AFS:

A sentient mold haunts a dilapidated luxury condo tower, feeding off the city’s buried past.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

AFS:

A lot of my research ended up looking into how the original Trump International Hotel and Tower Toronto (now The St. Regis Toronto) was financed, as well as various other debacles around major developments in Canada. While that tower was being constructed, I was working downtown just around the corner. After it was finished, I was there when glass fell off into the street below. I believe every early investor in Trump Tower lost money, while Trump made millions. He had nothing at stake. And this all started in 2002.

I was interested in how a tower could fail in a city like Toronto, when the sky is filled with cranes, how it could go on living after many of the original investors were driven to bankruptcy. It had an empty grand opening. The plaques are gone now, of course. The building has changed its identity. But the fact it exists at all is wild. It’s hard to stop a disaster once it gets moving.

Fungus is also a big part of the book. A toxic, sentient mold is integral to the story of The Marigold, and I ended up doing some research there as well. One of my favourite texts throughout this process was an incredible book by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. I only picked it up toward the end of the first draft, but what I found inside reaffirmed a lot of what I believed about the book I was writing and the function of my invented fungal mold in this polyphonic, layered story.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

AFS:

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, I was probably about half-way through writing the first draft of this manuscript. I set it aside for a couple months as I felt a lot of my assumptions about government apathy and civic irresponsibility might have been overblown. Maybe we were about to enter a new period of collective support and unity, maybe the systems we relied upon would protect everyone equally. It only took a few months for those illusions to implode and then I went back to the manuscript twice as hard as before, doubling down on the story I imagined.

This isn’t a pandemic book or a plague book or a response to COVID, but it was definitely influenced by how our governments and their corporate partners reacted to this overwhelming challenge, the ongoing attempts to downplay the struggles of our healthcare system, and the corruption thrumming through the soil across Southern Ontario right now. When financial interests overtake human welfare, we end up with hallways full of patients, cancers growing in bodies until it’s far too late, people dying alone in rotting apartments. Wealth is built on bodies—there’s no other way to accumulate it without grinding the rest of us into paste. It requires literal blood to keep the machine well-oiled and our leaders are happy to provide it when they must.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

AFS:

This novel is dedicated to my wife, Amy Jones, who is also an author. Amy is my first reader and editor. She is there when I’m pounding out thousands of words over a long weekend, trying to keep up with the demon in my head. She is there when I’m editing, ripping an old draft to shreds in search of something real and vibrant, of a story actually worth telling. And she is there through the constant rejections, the waves of “no” that crash over every writer who has been doing this as long as we have. And I am there for her when these roles are reversed.

It’s a rare thing and something I’m glad I could finally acknowledge with this book. It has been a while between published books for me and Amy was there for every part of this novel’s conception and execution. The Marigold does not exist without Amy. It remains scattered to the wind, a nightmare that occasionally wakes me up in the middle of the night, a spectre that haunts me on the subway right before the tunnel finally collapses. The next book though? That one might end up dedicated to the dog.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

AFS:

My novel has two epigraphs in the grand millennial tradition of citing a ‘serious’ literary figure to establish your bona fides and then a slightly less serious pop culture reference so no one thinks you’re too full of yourself. Maybe a lyric or a line from a reality TV show. We should keep doing this because it’s fun and because we all contain multiplicities and deep wells of shame.

The first is from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, one of my favourite books: “No one, wise Kublai, knows better than you that the city must never be confused with the words that describe it.” This is a book about Toronto, a city that exists despite itself, a city dedicated to annihilating its past. Its geography is always in flux and when I wrote this book, I played with it as I saw fit. I am not interested in realism, attempting to capture every perfect little detail. The city itself cannot be summarized in words alone. It is an interpretation of a place. It exists nowhere else.

The second epigraph is from former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford, now deceased. “Everything is fine” was one of many famous declarations he threw out there during his tumultuous reign, and everything was definitely not fine in the City of Toronto. Rob’s election forecasted much of what the city faces today—rising inequality, decaying infrastructure, a dedication to the car over all else—and his words spoke to what the ruling class continues to parrot even now. Everything is fine is the cry of the politician who wants you to look away from the rot, the short-turning streetcar that kicks you off in January, the landlord who paints over the black mold in the corner.

____________________________________________________________

Andrew F. Sullivan is the author of novels The Marigold; The Handyman Method (co-written with Nick Cutter); Waste, a Globe and Mail Best Book; and the story collection All We Want Is Everything, a Globe and Mail Best Book and finalist for the Relit Award. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario.