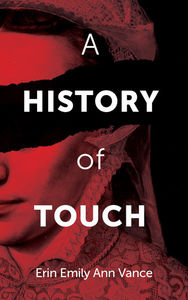

Erin Emily Ann Vance on Earning a "Poetic License" & Her New Collection of Silenced "Mad" Women's Voices

Hysterical. Emotional. Crazy. Words can be weaponized, and have been through history, especially when it comes to the behaviour of women and other groups who threatened a social or political status quo. In many cases these women were ill, disabled, or simply expressing themselves in ways considered too modern, too forthright, or too demanding. The consequences often went far beyond simple social disharmony, with the control exerted over these women going as far as disgrace, imprisonment, and even death.

In Erin Emily Ann Vance's A History of Touch (Guernica Editions) "mad" women are given a voice, from Biddy Early, a 19th century Irish herbalist accused of witchcraft to the horrifying case of Rosemary Kennedy, sister to JFK, who was subjected to a lobotomy without consent. Women who defied expectations, resisted traditional roles, and threatened tradition race across the pages, lifting the voices that were taken from them in life in Vance's sharp lyrics. Figures from folklore and history, by turns wry, raw, howling, or imparting wisdom, come alive here, channeled through Vance's empathetic pen.

We're excited to welcome Erin to Open Book to talk about her journey as a poet as part of our Poets in Profile series. She tells us about an 18-year old name tag that unlocked a potential future, about a headline linking DNA and trauma that sparked a new and influential interest in science, and about how she is known to occasionally "Frankenstein" one poem into another.

Open Book:

Can you describe an experience that you believe contributed to your becoming a poet?

Erin Emily Ann Vance:

I spent the majority of my childhood in search of magic. I believed fiercely that if I looked into a gopher hole long enough, eventually a pixie would emerge, or that when I wasn't looking, the algae on the pond behind our home morphed into a miniature Loch Ness Monster. I went to bed each night expecting to wake the next morning having sprouted fairy wings or a mermaid tail. Our family lived in rural Alberta, on a hobby farm, and when I wasn't inside reading, my brother and I were traipsing in the fields covered in pond scum, trespassing on neighbouring farms, and mapping out mythical lands. We held makeshift circuses to entertain our parents and grandmother, and I spent many afternoons writing to fairies. While any one of these childhood experiences could amount to the making of a poet, the defining moment for me was at a summer camp lead by Jennifer Aldred, where we read Shakespeare, made altered books, and I got to pretend to be a university student for two weeks before the start of 5th grade. On our final day, we gave a presentation to our parents and Ms Aldred made me a name tag that said: "Erin Vance: Fairy Princess. Poet." I still have that name tag. It sits on a little shelf above my desk alongside a "poetic license" that my brother gave me for Christmas one year. That name tag, which probably took Ms Aldred 2 minutes to make and print, gave me permission to live my life exactly how I wanted to. Eighteen years later, and I have a degree in folklore and am releasing my first full-length poetry collection, so I'm happy to say that I've lived up to that name tag!

OB:

What one poem—from any time period—do you wish you had been the one to write?

EEAV:

MOTHERBABYHOME (2019) by Kimberly Campanello, written in response to the legacy of Ireland's mother and baby homes, is a 796 page poem composed of archival materials and historical sources. It memorializes the countless women and children who suffered and died in Irish Mother and Baby Homes from the early 20th century up until the closure of the last home in 1998. The sheer vastness of this work places it in a category all its own, but the visual poems, hybrid nature of the work, and subject matter give it weight beyond the heft of the physical book itself. It is expertly crafted and written; taking so much from historical and archive sources dealing in such difficult subject matter is not easy, and Campanello has created something truly

OB:

What has been your most unlikely source of inspiration?

EEAV:

I find a lot of inspiration in chemistry and botany! Growing up, the class I disliked the most in school was science. I found it incredibly difficult and couldn’t find ways to connect with it like I could art, English, or social studies. I firmly considered myself “just not a science person” for most of my life; in fact, I think I might be the only person to have to take “Rocks for Jocks” at the University of Calgary twice! My interest in science wasn’t sparked in a geology lecture, or while looking into a toy microscope; I finally found an avenue into science through a summer writing residency! Marcello Di Cintio began a journalism workshop with an exercise based on a selection of newspaper headlines; one was about how childhood trauma has the ability to alter one’s DNA. For some reason, this piqued an interest in me and I ended up writing about a dozen poems based around what I found researching this topic. Now, I often use science as a gateway into a poem or series of poems, or as a way to add richer details to a poem. I’m working on a series of poems about William Morris and have spent many hours learning about the formulation, properties, and uses of arsenic.

OB:

Do you write poems individually and begin assembling collections from stand-alone pieces, or do you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

EEAV:

Both. A History of Touch didn't start as a collection, but there are poems in the collection that emerged together, or as parts of smaller projects. A few years ago, I wrote a series of poems about the use of Lysol disinfectant as a feminine hygiene product. They Said it Would Not Harm the Delicate Tissue was originally part of a longer suite! Washerwoman, Room, and Beautiful Bait were originally part of a series I wrote while travelling around Ireland studying history and folklore. Other poems emerged as singular entities, but as I began assembling this collection, they spoke to each other: I never intended for Rosemary's Lobotomy and Bloodletting to sit in conversation with each other, but I often work through extremely personal subject matter by studying and honouring women in history, and Rosemary Kennedy and Mary Roff both happened to be immensely important to understanding myself!

These days, I find myself thinking in terms of larger projects more often than of singular poems, simply because many of the subjects I wish to write about ask for more space and longer poems. I prefer shorter poems and vignettes, so that is how I bring those ideas to life.

OB:

What do you do with a poem that just isn't working?

EEAV:

When a poem isn't working, I put it into hibernation. I step away, let it sleep, and if I decide to come back to it, I usually approach it one of two ways: reworking (approaching it from a different perspective, chopping it up and rearranging it), or upcycling (pulling out lines, images, words, or metaphors and putting them in a separate file or notebook for later. I often use these bits of recycled poems as prompts for new work, but I also "Frankenstein" them into other poems that are missing something. It's amazing how often that missing piece was something extracted from an abandoned poem.

OB:

What was the last book of poetry you read that really knocked your socks off?

EEAV:

There are several books of poetry that I like to have at arm's reach at any given time, but one book that I have found myself reaching for over and over in the last two years is Annemarie Ní Churreáin's 2017 collection, Bloodroot. Ní Churreáin's writing is clear and distinct, and she approaches moments in history with a fierce reverence that I can only aspire towards. I first encountered this book at the Seamus Heaney Centre Poetry Summer School in Belfast, and have re-read it countless times.

_____________________________________________________

Erin Emily Ann Vance is the author of the novel Advice for Taxidermists and Amateur Beekeepers (Stonehouse, 2019) and five chapbooks of poetry. She teaches creative writing to children and teenagers and is the co-host of the folklore and history podcast Femmes Macabres.