Excerpt: Merilyn Simonds Explores the Spectacular Life of Louise de Kiriline Lawrence, a Woman Ahead of Her Time, in a Meditative New Biography

There are some lives that are so fantastical, so packed with passion and strange turns and reinventions, that they are hard to summarize. Such is the life of Louise de Kiriline Lawrence, a Swedish aristocrat born just before the 20th century began.

She turned her back on massive privilege to become a Red Cross nurse, whose Russian husband disappeared when they were both imprisoned during the Russian Civil War, and who, in a stunning second act of life, moved to Canada and ended up delivering the famous Dionne quintuplets. Caught up in the ensuing media sensation as she helped nurse the quints through their touch-and-go first year, she soon retreated from public life, starting a new, final chapter as a naturalist living deep in the woods.

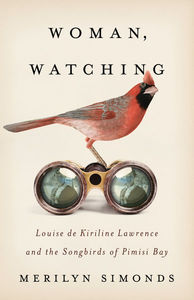

Acclaimed writer Merilyn Simonds set out to capture this epic life, in which de Kiriline Lawrence defied stringent expectations of her class and gender. The result is the riveting character study, Woman, Watching: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence and the Songbirds of Pimisi Bay (ECW Press), which focuses on de Kiriline Lawrence's later life as a naturalist and particularly, a respected nature writer on Northern birds. With praise from noted bird lover Margaret Atwood—who called Woman, Watching "lyrical, passionate, and deeply researched"—this is a portrait of a singular woman ahead of her time on issues of ecology and environment, class, gender, and more, and which also pulls in details of Simonds' own life and birding experience.

We're excited to present an excerpt, "This Gentle Art", from Woman, Watching today courtesy of ECW Press. Here we see de Kiriline Lawrence alone in her remote home after her second husband left to fight in World War II. Meditative and calming, Simonds beautiful, crisp prose takes readers into a day in de Kiriline Lawrence's life as she beings to discover yet another new self as an ornithologist and nature writer.

Excerpt from Woman, Watching: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence and the Songbirds of Pimisi Bay by Merilyn Simonds:

This Gentle Art

What a singular situation Louise found herself in that spring of 1940. In an abrupt twist of fate, she was suddenly free of both financial insecurity and the burden of farm labour. The business of living still made demands, but once she’d yoked water from the Little Stream that flowed down Peak Hill and had split and piled her day’s fuel wood by the cookstove, her time and her thoughts were her own.

In leaving for the war, Len had inadvertently given Louise a great gift—the gift of solitude. A certain relaxation comes with being alone. With silence. A space opens in the mind. Louise had built the cabin to fulfill an ardent wish to awaken every morning for the rest of her life with the sunrise in her face, to spend her days in quiet contemplation. Now at last she was free to follow her curiosity too—and what she was curious about was the natural world.

She and Len had set up bird-feeding tables a few metres from the kitchen window. They would scatter seed on the tables, toss breadcrumbs and kitchen scraps on the ground, and tie balls of beef suet to low-hanging branches. On the windowsills, Len had fastened narrow troughs to bring the birds close. She recognized only a few that came to feed, cousins of those she’d known as a girl in Sweden—woodpeckers, wrens, warblers, sparrows, and small chattery balls of fluff that reminded her of the titmice she used to watch at her father’s feeders. Len had taught her the common northern species—chickadees, blue jays, whisky jacks—but the brightly coloured birds that winged through her forest and nested deep in its foliage, appearing now and then at her feeders, were a mystery.

One beautiful May day the spring before Len left, a new bird landed on her feeding table. “He is sitting outside now watching some big starlings gobble up the feed on the tray—with sadness,” she wrote to her mother. “He is bright orange over the belly, breast, and under the wings, which are black and white. He wears a black cap over his head. He is quite big like a large domherre [bullfinch]. His wife is grey with a softer tone of yellow-green underneath and black and white on the wings. Not knowing yet his real name I call him Jelly-belly.”

Louise had trained as a nurse. She was used to calling things by their proper names. A leg bone was a femur. A lump in the breast was a tumor, either malignant or benign. She wasn’t content with “Jellybelly,” even though the bird did look as though it had nested in a bowl of orange marmalade. But who to ask for the scientific name? Not Len. And not her neighbours, who were farmers, trappers, and tree fellers. She knew no one educated in the science of birds.

A casual friend, hearing of her dilemma, loaned her a copy of Birds of Canada by Percy Taverner, a book that Yousuf Karsh, the Canadian photographer who created an iconic portrait of Taverner, called “an exquisite synthesis of poetry and precision.” When Louise tried to return the book, the friend told Louise to keep it, the book was hers.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“You should see us now running around the bush at the twitter of a strange bird, at the flutter of wings, book in hand to watch and decide what particular bird is nesting or flirting in our bushes and tree-tops. The Jelly-belly I wrote about last time is a Baltimore oriole, quite a rare specimen, beautiful to look at. They are nesting now and we don’t see them so often, but we hear their clear deep whistle every day. It is amazing what a variety of birds there are now that we are beginning to discover them, red like butterflies, yellow warblers, green tits, and purple finches. We have made friends with them all.”

Louise had few books at the time. What she had, she shelved not alphabetically or by subject but according to literary merit and their personal significance to her. And so she placed Birds of Canada between a biography of Madame Curie and Alice in Wonderland on one side, and on the other, H.G. Wells’s Science of Life and Edward Lear’s Nonsense Songs and Stories.

How difficult it must have been to learn about birds solely from a book. I learned from my Uncle Syd the summer I was nine, when he and Aunt Lizzie joined my family at a cottage in Muskoka. I’d perch on the arm of his big old wooden lawn chair, leaning in to study the illustrations in his Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America by Roger Tory Peterson. Published in 1934, the same year as Taverner’s Birds of Canada, the Peterson guide was a quarter the size and fit easily into the pocket of Uncle Syd’s bush coat. When he died, I got the book and put my blue checkmarks beside his pencil marks in the life list at the back.

Even so, there are some birds I never recognize. From the balcony of our bedroom in Mexico, Wayne and I watch a bird, brown as a sparrow but too chunky, its tail too long. I feel what I always feel when meeting someone who looks familiar but the name escapes me. I should know this bird! I see a flash of rusty rump and the name comes to me: canyon towhee, a bird I first saw at the Grand Canyon. William Beebe in his book Two Bird-Lovers in Mexico calls it a brown towhee. We watch it slip under the bougainvillea and over the adobe wall of the house, more mouse than bird, as Beebe says, though its persistent singing is as welcome as a nightingale.

Louise must have felt Taverner was writing directly to her. For the first time in her life, at the age of forty-six, she was without a project, without a job, without anything that made her feel valuable in the world. In the Introduction to Birds of Canada, he laid out the best way to study birds, pointing out the personal and scientific value of such study, not only for the bird watcher, but for the nation, and most importantly, for the survival of the birds themselves. The distribution of birds in Canada was far from known at the time: the bird populations of vast areas were based on assumption; many provinces lacked even an up-to-date, authoritative bird list.

Inspired, Louise bought a large black scribbler and on the first page printed in bold letters: NOTES ON BIRDS AROUND OUR HOME. She allowed one page per species, flipping to a fresh sheet each time she positively identified a new bird.

Her notes on these first sightings read like story fragments.

“Saw you love-making so close to me in the thickets that I could have touched you,” she wrote of her first Canada warbler. “In fact you almost took off my nose in your ardor.”

“I saw you feeding a young daughter today at the suet,” she wrote of a hairy woodpecker. “Are you especially early?”

And of the ovenbird, “Well, now you are feeling quite at home very near to the kitchen window and bird bath.”

With great excitement, she wrote to Taverner about her remarkable finds. “I have long moments of pleasure watching this scarlet vision against snow and evergreens. An old trapper came here the other day and as soon as he saw it, he exclaimed, ‘Ah, mais ça c’est porte bonheur! ’ [That’s a harbinger of happiness!] He had never seen one in this bush before.”

The delight of seeing a brand-new bird is a bit like the bliss of love at first sight. One Sunday, as I walked in the Charco del Ingenio, a wild canyon above San Miguel de Allende, a chunky grey bird with a thick mustardy beak landed on a cactus in front of me. Its crest was tall, brushed scarlet at the tip; around its beak, a splash of red that dribbled down its belly, as if it had just gorged messily on cherries. It looked at me and let out a thin slurring whistle, what-cheer? what-cheer? I stood rapt as it tore at the fruit of the cactus, just as the cardinals back home would tear into late apples in our orchard. And sure enough, the bird was a desert cardinal—a pyrrhuloxia, cousin to the red cardinal that brightened Louise’s winter.

Northern cardinals had been recorded at higher latitudes than Pimisi Bay, Taverner told Louise, but her sighting of a black-billed cuckoo marked the most northerly record of that bird. “This is one of the great things in bird study. There is always something new to look forward to, with thrills spaced evenly enough to sharpen the interest. If this gentle art is a relief from the sterner atmosphere that surrounds us, it is a blessing indeed. We need such relief these days. If I have had any hand in extending it, I can feel that I have been of some use in the world.”

Wars, disease, personal tragedy: birds are oblivious to our human trials. Writing this book during the Covid-19 pandemic, I feel the truth of Taverner’s words. The song sparrows and Caspian terns outside my window are carrying on with their lives, trilling and screeching, nest-building and mating, the young hatching and trying their wings: stages in a life that remind us of the calm unrolling of our own lives, too, regardless of the immediate upheavals we are suffering through.

“Blessed be these birds!” Louise wrote back to Taverner. “With them it is quite impossible to feel one instant of loneliness or boredom.”

_____________________________________________

Excerpted from Woman, Watching: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence and the Songbirds of Pimisi Bay by Merilyn Simonds. Published by ECW Press. Copyright 2022 by Merilyn Simonds. Reprinted with permission.

Merilyn Simonds is the author of 18 books, including the nonfiction classic The Convict Lover, Gutenberg’s Fingerprint, and most recently, the novel Refuge. The founder and first artistic director of the Kingston WritersFest, Simonds is an influential champion of writers and writing. She lives with writer and translator Wayne Grady and divides her time between Kingston, Ontario, and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.