Fascinating and Notorious Mining Mogul Viola MacMillan Has Her Story Told in Windfall

Canada's history in the mining industry contains many stunning and nefarious stories that most are unaware of. Around many of our Ontario cities and towns, for example, there are streets, neighbourhoods, and institutions that bear that names of some of the most formidable and corrupt figures who participated in the growth of the province via this particular sector.

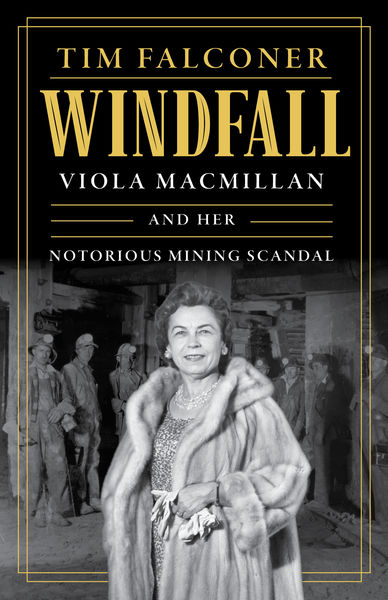

Amongst those stories is the fascinating account of Viola MacMillian, who started out as a prospector in the 1930s and went on to achieve great success, fortune, and influence in developing mining projects, and who was always in pursuit of a massive discovery that would change everything. In the new nonfiction work, Windfall: Viola MacMillan and Her Notorious Mining Scandal (ECW Press), author Tim Falconer explores the trajectory of MacMillan's life in mining, leading to the scandal and fraud of Windfall Oil and Mines.

This fated and catastrophic endeavour forever changed the industry in Ontario, and pegged MacMillan as a notorious huckster who lost investors untold riches. But, this was not where her story ended, not even close.

To find our more, check out this True Story Nonfiction interview with the author, right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Tim Falconer:

Viola MacMillan was a remarkable woman. She first went prospecting in the 1920s and then she and her husband became full-time prospectors in the ‘30s. As you can imagine, there weren’t many other women doing that at the time. Or any, really. Soon, she discovered a talent for the business side of the industry. She kept on prospecting, but also put together mining deals.

In the early 1940s, she became the president of the Prospectors and Developers Association (now the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada, or PDAC), which was practically a male fraternity at the time; she held the job for the next 21 years. She had her first producing mine in the late ‘40s. She was even more successful in the ‘50s and became a minor celebrity in Canada.

And then, in July 1964, at the age of 61, she found herself at the centre of a high-profile stock scandal.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In April of that year, Texas Gulf Sulpher, an American mining giant, announced that it had discovered a massive deposit of copper, zinc and silver near Timmins. This led to a huge staking rush as prospectors headed to the area. Texas Gulf had tried to get the mineral rights to all the promising ground around its find, but because of a staking error, it missed out on four claims. MacMillan bought them and sold them to Windfall, a company she controlled.

Before drilling started on July 1, Windfall’s stock was trading around 60 cents a share. But a few days later, MacMillan’s husband George decided to stop the drill. This fed rumours that the company had found an ore body. The speculation pushed the share price higher and higher. Soon it was at $5.70. Still, Windfall wouldn’t release any results or give any indication of what was in the first hole. Finally, the company announced it had found no commercial mineral values in the hole. And the stock crashed.

So many small investors lost money that the premier of Ontario announced a royal commission to look into what happened. After the commission report came out in 1965, police charged Viola and George MacMillan with fraud. They were later acquitted, but by then, Viola had already been convicted of wash trading, which is trading with yourself to make a stock look active. It was a common activity, but one that rarely resulted in charges. The authorities seemed to want to make an example of her. She was sentenced to nine months but served only nine weeks and her early release created another controversy.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

TF:

The question that stayed with me the whole time I worked on this book was: why did she do it? She seemed to have it all; she was successful, respected, wealthy—and even she even had political influence as the head of the Prospectors and Developers Association. Why would she risk all that?

Maybe I am naïve, but I figured it had to be more than just money. She never provided an answer; in fact, she always claimed to be completely innocent. But at the end of the book, I try to understand what made her do it.

OB:

A lot of nonfiction prizes and anthologies have expanded to welcome more personal nonfiction as well as strictly research-based nonfiction. What do you think of this shift within the genre?

TF:

You’re trying to get me in trouble, right?

There’s an element of memoir in Bad Singer: The Surprising Science of Tone Deafness and How We Hear Music, a previous book of mine. But I also did a great deal of research, so I don’t consider it a memoir.

To be honest, I don’t read many pure memoirs; I prefer researched non-fiction and novels and short stories. I am fine with other people writing memoirs and I especially enjoy reading ones by people I know.

I am also fine with memoirs winning prizes. But it bugs me that it now seems easier to get grants for a memoir than for researched non-fiction. Ken Whyte, the Sutherland House publisher, has covered this often in his SHuSH, his excellent Substack newsletter. One edition included the story of how a Canada Council bureaucrat told a publisher, “We don’t like fact.” Do I even need to make a comment about the state of democracy here?

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

TF:

Writing non-fiction means never having to suffer writer’s block. If I am stuck and can’t figure out what to write, I know I haven’t done enough research. Once I have the material I need, all I need to do is decide what to keep and what to cut, figure out how to arrange it and try to write it in a compelling way.

That doesn’t mean I don’t get discouraged. My last book, Klondikers: Dawson City’s Stanley Cup Challenge and How a Nation Fell in Love with Hockey, was my first stab at historical non-fiction. I blindly assumed there would be lots of archival material—including diaries and letters—to work with (it never dawned on me that if there had been, someone else would have already written a book I wanted to write). So I was often frustrated because I could not find the information I sought. Of course, that made each discovery all the sweeter.

My experience with Windfall was completely different. I was able to work with thousands of pages of transcripts from the royal commission and the Ontario Securities Commission inquiry. That meant that even though all the major characters are dead, I had them testifying under oath. I also had all the magazine and newspaper articles about MacMillan going back to the 1930s. She also wrote an autobiography and there are 66 boxes of her papers in the archives of the Canadian Museum of Nature. I had it so easy with this book.

OB:

Do you remember the first moment you began to consider writing this book? Was there an inciting incident that kicked off the process for you?

TF:

I had never heard of Viola MacMillan or Windfall, even though I studied mining engineering at McGill for two years before switching into English literature (my standard joke was that English was the next subject in the university calendar). I also spent three summers doing exploration for mining companies and worked in two mines (one in Ontario and one in the Yukon). Later, as a magazine journalist, I didn’t write often about mining, but when I did, I enjoyed it.

In 2021, after finishing an article about a mining company, I wondered if there might be a mining story that would be worth a book. As soon as I read about MacMillan and the Windfall scandal, I knew what I wanted to write this book.

OB:

What defines a great work of nonfiction, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.

TF:

Great non-fiction is a fascinating, well-researched and well-written narrative. Even better if the story allows the author to explore larger themes. Picking just two is not easy, but I will go with a couple of relatively recent ones: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot and Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann. I note that neither of these powerful and important titles made the recent New York Times’s list of the best books of the century (so far). I found that appalling.

OB:

What are you working on now?

TF:

I am still looking for my next book idea. I’ve started a new job as the executive editor of Up Here, a magazine about the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, so I am having a lot of fun and not fretting too much about not having my next idea. But I wonder if this job will lead me to write another book about the North.

________________________________

Tim Falconer’s last two books — Bad Singer: The Surprising Science of Tone Deafness and How We Hear Music and Klondikers: Dawson City’s Stanley Cup Challenge and How a Nation Fell in Love with Hockey — made the Globe and Mail’s top 100. He lives in Toronto, ON.