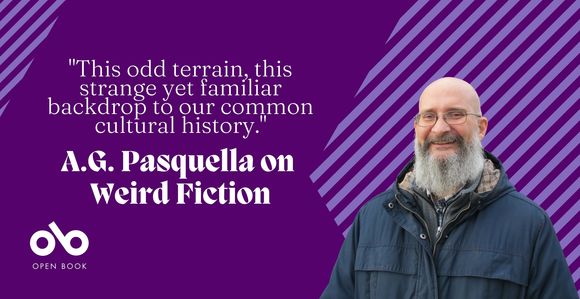

Guest Essay: A.G. Pasquella on Slipstream, New Weird, and the Wonderfully Strange History of "Weird Fiction"

A.G. Pasquella knows weird. He can do straight-laced and tightly plotted fiction, like his celebrated Jack Palace noir series, but he's equally known for his experimental, offbeat, and wonderfully wacky creations, published in places like McSweeney's, Broken Pencil, and Joyland (the latter of which published his delightfully titled short story "I Was a Teenage Minotaur").

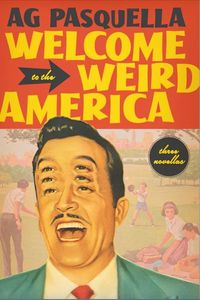

His newest book, Welcome to the Weird America (Wolsak & Wynn), collects three of his most joyfully surreal novellas: Why Not a Spider Monkey Jesus?, NewTown, and The This & the That. The stories include characters like a monkey televangelist and a teenage boy attempting to overthrow a spaceship admiral, and play with genre in innovative and inventive ways.

To celebrate the publication of Welcome to the Weird America, we're hosting A.G. as a guest essayist today on Open Book, where he discusses the rise of the genre sometimes known as "weird fiction" and its long history, why it is tough to define, and why genre, in all it's malleable, changeable, often debatable glory, is so fascinating as a construct.

Welcome to Weird Fiction

A.G. Pasquella

What makes fiction weird? Good question! Is weirdness in the eye of the beholder? Is it a “I know it when I see it” situation, to borrow a phrase from former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart?

Well, yes. Traditionally, though, “Weird Fiction” is a genre that is horror-oriented, featuring supernatural creatures like the many-tentacled creations of that ol’ racist H.P. Lovecraft. This type of fiction can be found in the glorious horror pulp magazines of the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. The premier pulp mag of this type was Weird Tales, which ran for 279 issues, from 1923 to 1940. You knew the tales were weird because it said so right on the cover.

My book Welcome To The Weird America doesn’t fall into this old-school category of Weird Fiction. So, what about the genre known as “New Weird?” These are stories influenced by the creepiness of Weird Fiction but have more of a speculative bent. New Weird stories mix in elements of fantasy and science fiction, like in the works of China Miéville, Justina Robson and Jeff VanderMeer.

‘New Weird’ is closer, but it’s still not quite right. Maybe Welcome to the Weird America could fall into the 'Slipstream' subgenre of Weird Fiction. Slipstream? What the heck is that? You’re right, this one’s much trickier to pin down. The term itself was invented by Richard Dorset during a conversation with the one and only Bruce Sterling. They were talking about fantasy books that didn’t quite fit neatly into the fantasy genre. “They’re not mainstream,” Sterling said. Dorset replied, “Why not slipstream?” And thus a subgenre was born!

Slipstream, according to Wikipedia, is “a literary genre that pushes the boundary between traditional fiction and either science fiction and/or fantasy.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slipstream_genre) But... is it? Is it even a genre? Some believe Slipstream is more of a feeling, a cognitive dissonance, a literary effect that leaves the reader feeling very strange. (See James Patrick Kelley and John Kessel’s collection Feeling Very Strange: A Slipstream Anthology.)

Slipstream has been described as “nonrealistic fiction with a postmodern sensibility.” Which is true enough, but that’s a pretty broad definition that could cover a whole lot of books!

The absolute best description for my novella Why Not A Spider Monkey Jesus? (which is one of the three novellas collected within Welcome To The Weird America) I ever heard came from my friend singer/songwriter Corin Raymond, who described it as 'Science Fiction Cartoon Noir.' That's it in a nutshell! Here’s the problem, though: just try walking into a bookstore and asking the staff to point you in the direction of the ‘Science Fiction Cartoon Noir’ section!

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Let’s set aside ‘weird’ as a genre for a minute and look at the word itself. Yes, weird can mean supernatural or uncanny but it can also mean strange or bizarre. Ah, now we’re talking! My novellas don’t have a supernatural bent but they are definitely bizarre!

The novellas in my book are inspired by what Greil Marcus calls ‘the old, weird America,’ which he discusses in his book The Old, Weird America (go figure) and which I tip my hat to in my book title.

Greil Marcus’s publisher calls ‘The Old, Weird America’ "This odd terrain, this strange yet familiar backdrop to our common cultural history.” Luc Sante, in New York magazine, called it the 'playground of God, Satan, tricksters, Puritans, confidence men, illuminati, braggarts, preachers, anonymous poets of all stripes.'"

This is the America of my book, too, and this America is weird indeed. This is the old sepia-toned America of strange roadside attractions and near-forgotten performers, like Glurpo The Underwater Clown and Ralph The Swimming Pig.

Check out some black and white pictures of Glurpo The Underwater Clown. He is not just odd or strange or bizarre, he is also creepy as Hell. He’s like some dripping nightmare out of a long-lost story by Edgar Allan Poe. Poe, by the way, is considered to be the spiritual forefather of... you guessed it... Weird Fiction. Quoth the raven: Keep It Weird!

__________________________________________

A.G. Pasquella’s writing has appeared in various spots including McSweeney’s, Wholphin, The Believer, Black Book, Broken Pencil, and Utne Reader. A.G.’s story “I Was a Teenage Minotaur,” originally published by Joyland, was included in Imaginarium 2013: The Best Canadian Speculative Writing. Pasquella has published three novellas: Why Not a Spider Monkey Jesus? (which also appeared as a thirty-page excerpt in McSweeney’s #11), NewTown, and The This & The That. He is the co-editor (along with Terri Favro) of PAC’N HEAT: A Noir Homage to Ms. Pac-Man. A.G.’s three crime novels in the Jack Palace series – Yard Dog, Carve The Heart, and Season of Smoke – were published by Dundurn Press. When he’s not writing, A.G. makes music with the bands Miracle Beard and Lasergnu. A.G. was born and raised in Dallas, Texas, and now lives in Toronto, Ontario, with his wife and their two children.