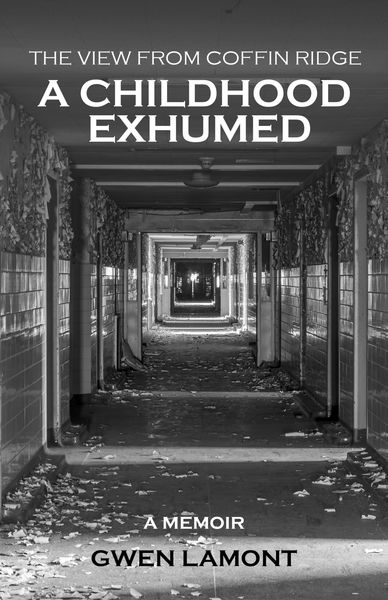

Gwen Lamont's Young Self Writes Her Way Home in The View From Coffin Ridge

As an academic with a deep understanding of the impact of trauma, Gwen Lamont used what she had learned from her own life to bridge the gap between her story and those that she studied and researched. She later carried on down this path by becoming a social worker and then a psychotherapist.

After completing an MFA from University of King's College, Halifax in 2019, Lamont gained traction with creative non-fiction and was even a finalist for the 2023 CBC Non-Fiction Prize. Now, the author has arrived with a powerful new memoir that began on that MFA program, recently published by newly-minted OBPO member, Ginger Press.

In The View from Coffin Ridge: A Childhood Exhumed, the author delves deep into the past and her own childhood. After many successful years in academia and professional life, Lamont was haunted by her upbringing and experiences, and eventually realized that her younger self would have to be allowed to write her own story if she were to fully confront her trauma and truly live with it.

Read more about this enthralling new work in this My Story Memoir Interview!

Open Book:

How did your memoir project first start? Why was this the right time to tell your story?

Gwen Lamont:

The word memoir has several dictionary meanings: autobiography, biography, monography, narrative, record, but there is one that stands out for me: to give an account. Often people are able to give a verbal account of their lives and, in my experience, most people have a coming-of-age story. But my story, from the age ten to twenty, was something about which I never talked to anyone, ever, except in the broadest of terms: I lived here, moved there, this town, that city, went to these schools, that sort of thing. But the details? Those I never shared. I had promised never to tell anyone about the many things that had happened to me, and I never spoke of the things I had done. Shame is a hiding emotion and that’s what I felt much of the time. But family secrets have a way of entering our lives whether we want them to or not. And one night, in the vineyard at Coffin Ridge, the memories of the young girl I had once been made a final push into my life. She wanted to be heard, to be seen. That night writing the account of my life began.

I was forty by the time the young girl I had once been began to push her way into my current, well-constructed, life. The most likely explanation for this lack of verbal history, it seems to me now, was a result of not paying attention to my young self for so long. Ignored, she disappeared, or was buried in the crevice between then and now. Both involve intention, a protection of my now self, from my former history. On the outside my life looked successful. To my friends I looked happy and thriving. Though I hadn’t completed grade nine—another thing no one knew about—I now had three university degrees and a career as a social worker. I had recently completed research on femicide. I was married, had children. I looked to be living a charmed life, but all was not right with my world. Rather than feeling charmed, I felt haunted.

I once saw a documentary about the cave people and how they drew on cave walls, thus proving their existence. It was after the young girl I had been and the memories of her life began to infiltrate my present day life that I was compelled to write about my life to prove her existence. It wasn’t as if it felt like it was the right time exactly, it felt as if I didn’t have a choice, that it was now or never. I chose now. Maybe that’s what I was doing: making myself visible. She forced me, in a way, to give an account of her, to accept her into my life. But in order to do that I had to find her and that involved research. That is how my memoir started.

OB:

Did your memoir change significantly from when you first started working on it to the final version? Was there anything that surprised about the process?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

GL:

My memoir changed considerably from the beginning to the end. I think this is because of the process which was: I travelled to, and spent time in, the places where some of my young life had unfolded. I immersed myself in the experiences she/I had had in those places. I interviewed friends and family. After, I would write trying to recapture, as closely as possible the experiences. The compulsion to document an account of the circumstance of my family and my place in it was strong, as compulsions are.

One of the many surprises about the process was how long it took. The research took many years and then it took many more years to develop my writing skills, and then more time to gain the confidence, which is always necessary when telling a difficult story. In order to help me gain the confidence necessary to write I attended the Humber School for writers one summer. Then I did a self-directed residency at the Banff School of Arts. During that time, I wrote the most difficult piece of my story, replicating, as it were, my experience of being locked in a small room with little interaction with the outside world. The piece I wrote there barely changed in the future, so well had I captured what that time had felt like for me. Once the manuscript was ready, I did an MFA in Creative Non-Fiction at University of King’s College in Halifax. The mentoring aspect of the program helped me gain the confidence I needed to publish.

The other pleasant surprise was how much I loved to write, how writing allowed me entrance to a zone I had never experienced before. It was a zone I couldn’t get enough of. I know that many say writing is hard, but for me the writing was easy; it was the editing and the structuring that were much more difficult.

OB:

If you have written in other genres, what was different for you in writing a memoir.

GL:

The writing I had done in the past was academic in nature. My Master’s thesis was entitled The Subjective Experience of Men Who Murder Their Intimate Partners and, in that instance, it was the research aspect of my thesis which was more enthralling. The writing was a matter of fact and more objective. But writing my young self back home was a more immersive experience, more subjective and experiential. I agonized over every word, every sentence, every paragraph. I took each of my chapters to my therapist and read them to him. It was how I began to tell others about what had happened to me. There is also a psychological piece to grapple with when writing about your life and difficulties you have experienced. I had to overcome shame which isn’t something I had to do in academic writing. I had to accept my life experiences in a way I did not have to when I was interviewing murderers.

OB:

Did you experience any anxiety about making a part of yourself public in this way? If so, how did you or do you cope with the vulnerability of publishing a memoir?

GL:

When I pitched my book, and in order to describe my complex story, my pitch was this:

The View From Coffin Ridge: A Childhood Exhumed is Girl Interrupted meets the Liar’s Club at the Glass Castle. My memoir shares aspects of each of those memoirs so, as you can imagine, I had extreme anxiety about sharing my memoir. Anxiety, in my experience, is linked to shame and shame was the first emotion I had to overcome. I first launched my book to 200 people, many whom had known me⎯or thought they had known me—and the anxiety I had was hard to manage, but I also knew I didn’t have a choice. My story Survivor’s Guilt, had been longlisted for the CBC Creative Non-Fiction Prize in 2023, a story I read at each of the 14 launches I have had to date. Although that story is not part of the book, the subject of intimate partner violence is one of the themes of my memoir. Before each launch (over 700 people now) I recite the names of some of the murdered women about whom I write. In this way I have been able to read from my book and talk about my life. I believe strongly that memoir can change lives as so many have changed mine and this made publishing my memoir purposeful.

OB:

Personal essays, memoirs, and creative nonfiction in general have becoming particularly in demand and loved by readers in recent years. Why do you think creative nonfiction is more popular than ever.

GL:

The great rebel poet Muriel Rykeser wrote this: "The world is made up of stories not atoms. What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The whole world would split open."

And that is what happened to me. The world split open. And just as I write this, I have signed a contract with Dog Eared Productions for them to write a screenplay for a feature length film based on my memoir. We write memoirs to see who we have been and therefore who we are. We read memoirs to see our shared experience, our shared humanity. We read history to understand our own history and in order to find our place in the world.

As I’ve launched my book around the province, I have heard this one thing more than any other:

A woman walks up to me, grabs my hand and says: Because you wrote your story, you have given me permission to tell mine. Many women, who have held on to secrets and who have kept promises, tell me they too were almost killed by an intimate partner, or they too lived in poverty, or they too had an alcoholic parent and that reading my book has made a difference in their lives. The other thing I often hear is how, as they read my memoir, they were surprised that, while my story is sad in parts, it is also funny and hopeful. When I hear that I know that my agonizing over structure has worked and that I haven’t produced a misery memoir but a story the reader won’t soon forget.

_______________________________

Gwen Lamont was shortlisted for the 2018 Geist Postcard Contest for What’s in A Smile and long-listed for the 2023 CBC Non-Fiction Prize for her short story Survivor’s Guilt, from over 2300 entries across Canada. Ginger Press recently published The View From Coffin Ridge: A Childhood Exhumed, now available to order. She lives on a vineyard between two ghost towns in rural Annan, Ontario where she writes and also is managing partner of Coffin Ridge Boutique Winery.