"I Can’t Help but Care, and So I Write and I Speak Up" Elizabeth Allua Vaah on the Power of Titles & Motherhood

In a small village in Ghana, an 18-year old widow makes a vow to change not only her fate but the fates of her children and many women around her. Young Ahu has no choice to remarry, but in every other way she manages, through sheer grit and will, to shake off the shackles that come with her gender. Opening a small eatery, she educates her children and even sends her eldest, Bomo, to university, breaking a cycle of limitations and expectations.

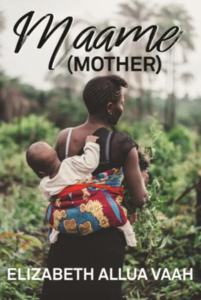

Ahu's story—as well as Bomo's, and other women in their community—is told in Elizabeth Allua Vaah's Maame (Mother) (Mawenzi House), an electric story collection that will transport readers right beside these inspiring women.

Celebratory, tough, and powerful, these stories, which make up Allua's debut full length work, explore the nature of motherhood through fascinating and vivid characters.

We're excited to be speaking with Elizabeth today as part of our Entitled series, which digs into the meaning and importance of titles. She tells us about how and why Maame (Mother) got its name, the book title that she absolutely loved, and why "Maame" was the right "mother" to choose for her title.

Open Book:

Tell us about the title of your newest book and how you came to it.

Elizabeth Allua Vaah:

My book is titled Maame (Mother). It celebrates mothers—both biological and foster mothers—as well as motherhood. In many communities women are expected to take on, and do take on, mothering roles, which they perform so well it is seen as second nature, so natural that we take it for granted. Maame not only celebrates mothers, but also brings out some of the struggles these women in rural communities have to deal with and the sacrifices they have to make to see their children go further than they could.

OB:

What, in your opinion, is the most important function of a title?

EAV:

A title should convey the essence of a story. Whenever I am reading a story I subconsciously return to the title over and over to remind myself of how what I am reading aligns with it. I see it as the distillation of the entire book into a word or a phrase.

OB:

What is your favourite title that you've ever come up with and why? (For any kind of piece, short or long.)

EAV:

I wrote a blog post recently which I titled “Musings of a hyphenated Ghanaian.” There is an ongoing dilemma with many immigrants when it comes to happenings in their country of birth: should you care, and why? I have gotten that question so many times that I decided to answer it in a blog post. In this case I knew what I wanted to write. Settling on the right title came later. Here I find one word especially poignant. For a while I teetered between “dilemma” and “musing,” but settled on the latter because—no, I wasn't facing a dilemma of whether or not to care. I can’t help but care, and so I write and I speak up. This was more my thinking aloud about why I can’t keep quiet.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What is your favourite title as a reader, from someone else's work?

EAV:

I have a few. However, Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere is at the top. While reading the book I kept seeing the title on every page, literally and figuratively.

OB:

Did you consider any other titles for your current book and if so what were they? Why did you decide to go with the title you eventually picked?

EAV:

I knew my title was going to have “mother” in it. I was going to use the Nzema word ɔmɔ (“mother”) as the title. Then I realized, how would non-native speakers search this word online? Then I tried Omo—except it is a popular detergent in Ghana. Eventually I settled on Maame, another word used for “mother,” but one that doesn’t need special characters on the keyboard.

OB:

What usually comes first for you: a title or a finished piece of writing?

EAV:

None of the above. I usually start with the writing, then at a certain point in the piece the titles start circling in my head. I don't usually finish the writing before coming up with the title: as the ideas begin to crystallize on the page, the possible titles begin to appear as well. By the time I am done writing, the title is ready. Choosing the title is more a matter of practicality, as it was in the case of choosing between ɔmɔ and Maame.

OB:

What are you working on now?

EAV:

I am working on a novel I have titled Bulu, Taboo Child. It is about a tenth-born child in a family from a community that sees such children as evil.

____________________________________________

Elizabeth Allua Vaah hails from Bakanta, a small village on the western coast of Ghana, West Africa. She was the first in her family to attend high school and one of the first few girls in her village to go to university. Maame is Allua’s first work of fiction.

Allua is an advocate for better maternal health through her foundation, the Vaah Junior Foundation. She is a strong advocate for girl child education, never failing to use her own life story as an example of how girls’ education impacts generations. Allua lives in Canada with her family and works as a Risk Manager at a major bank in the Greater Toronto Area.