Jennifer Maruno on Dreams, Bedtime, and What She Learned from Reading 40,000 Picture Books

If you put kids to bed at night, you know that bedtime can be chaotic, but that there can also be an element of magic in those few quiet moments with little ones as the lights go down and the coziness of sleep rolls in. In Jennifer Maruno's While You Sleep (Pajama Press) that magic is real: as a little girl goes to bed, her mother gently urges her to sleep so that the night-helpers can begin their work. Who are the helpers? A group of otherworldly bunnies who paint flowers bright colours, dust butterflies so they can flitter, and charge rainbows to arc across the sky.

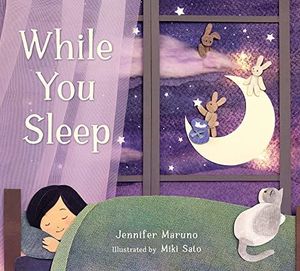

Infused with wonder and faith in the fantastical, While You Sleep is told is song-like rhyming couplets that rock readers into their own dreamy world, perfectly captured in Miki Sato's ethereal collage art, which makes use of not only paper but also textiles including embroidery silk.

A book about believing the world could be just a little bit better and more beautiful when we wake, While You Sleep is hopeful and magical. Maruno, who honed her ear for rhyme and feel for storytelling as a parent and educator, knows how to look at the world through a child's eyes. The book has already earned a coveted starred review in Kirkus, signalling a rare and special picture book from a writer who intuitively understands the genre.

We're speaking with Jennifer about While You Sleep today about While You Sleep. She tells us about what she learned from reading a staggering 40,000 picture books aloud during her career as an educator, why rhyming books sometimes get a bad rap, and how one of her own children inspired the book's premise with his curiosity about dreaming.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Jennifer Maruno:

Dreams are universal human experiences. They can be happy or haunting. While You Sleep is a rhyming picture book about a small child’s sweet dreams. Night-helpers, which turn out to be her own toys, care for the world overnight, stuffing clouds, painting flowers, and dusting butterflies, to make the earth beautiful once again.

One of my own children dreamed so deeply and intently he often woke up late at night wanting to know what was going on in his head. It became important for me as a mother to create a landscape of comfort for both my children before they closed their eyes for the night.

Since parents use the bedtime story as a way of decompressing from the countless number of stresses that their children experience, I wanted the cadence of While You Sleep to lull children into their own sweet dreams. While You Sleep resembles a lullaby for that reason.

OB:

Is there a message you hope kids might take away from reading your book?

JM:

I hope there are two inherent messages in the book. The universal elements of sky, sun, moon, constellations, and clouds are universal and spectacular in every way. We do not need to burden young children with the worries of climate change. We should show them how to appreciate the world’s beauty as it is. That appreciation is what will lead to greater care of the planet as they grow older, not through a sense of imposed responsibility.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Also, parents need to understand that the bedtime story is a precious time to be with loved ones, fostering the imagination that creates sweet dreams.

OB:

What defines a great book for young readers, in your opinion?

JM:

My career as teacher, primary consultant, and elementary school principal has given me the opportunity to read over 40,000 picture books aloud. That doesn’t even include the ones I read to my own little ones or to their little ones. It’s safe to say that I am more than just a proponent for the picture book. Having seen it’s power of enchantment and thoughtfulness wash over children repeatedly, I know is a necessary element of child development.

A good picture book relies on three components: words, illustrations, and listener.

Children will always attend to the physicalness of language. A word can make them smile just by the sound or scrunch their face at the strangeness of it. I used rhyming couplets to create my magical dream world. There’s a general belief that rhyming books are passé, but I think that’s because there is nothing worse than bad verse. (sorry!). A writer has to be wary of forced rhyme or the drawing out of a word to make a rhyming beat. Rhyme must have a sonic flow, a happy repetition that makes perfect sense.

The author can control the words, but the illustrator brings an interpretation to the words that doesn’t just compliment them but becomes a second story. I was honoured to have Miki Sato’s collage art, which combines paper, textiles, and embroidery silk, to create a three-dimensional dream world adding to the fantasy and magic.

Young listeners always find comfort in knowing that the twin lines of a text will “match.” When language flows in a meaningful way the listener begins to hear it in their mind. After a few readings they will know exactly what those matching words will be, sometimes shouting them out, sometimes murmuring to themselves.

Little listeners will not tolerate a reader changing words or leaving out parts of the tale. If the words and illustrations enchant or provoke thought, the story will be requested often. A favourite picture book gives a child a sense of ownership and makes for a satisfying experience.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

JM:

Time and tea are the biggest criteria of my writing mind. I spend a lot of time mentally inventing which looks like staring over a steaming mug. Ideas also come while weeding the garden or watching the world go by as a passenger in car or train. I took an early retirement from the world of education in order to grant myself the time necessary to process thoughts to the point of putting them down on paper.

I use a lot of sharp pencils and pads of paper. I never erase, just cross out, knowing I just might need that thought later. There is always a pile of jumbled thoughts next to my computer. I usually know the top and bottom of a story but work more like a quilter piecing scraps together to create the middle.

The computer is the biggest asset for today’s writer. Cut and paste no longer involves real scissors and glue. Fragments can be saved for another project. Some writers I know compose directly on the screen. I need to see words on paper before I go to the keyboard. I don’t edit from the screen either. I need a print-out to mark up.

All writers need their “Peeps.” I am fortunate to live in an area full of talented children’s writers. We meet regularly as a group reading our words, continuing through Zoom throughout the pandemic. They are more than happy to call out any sticky meter or unsettling rhyme and I love them for it.

OB:

What are you working on now?

JM:

For something completely different, I’ve got a picture book coming out with Groundwood Books, illustrated by Vivian Rosas, titled Momma’s Going to March. It’s a look over time as to why women have taken to the streets in protest of the many injustices around the world. The cadence of the language in this text comes from the repetitive phrase of marching.

__________________________________________________

Jennifer Maruno is the author of seven novels for middle grade and young adult readers as well as the picture book Moose’s Roof. Her novels have been nominated for the Pacific Northwest Young Readers Choice Award, the Hamilton Arts and Culture Award, the Rocky Mountain Book Award, and more. She received her Bachelor of Arts from Waterloo University and Master of Education from Brock University. Formerly the Vice-President of the Canadian Society of Children’s Authors, Illustrators and Performers, among other literary roles, Jennifer currently enjoys writing and mentoring other writers full time. Jennifer lives in Burlington, Ontario.