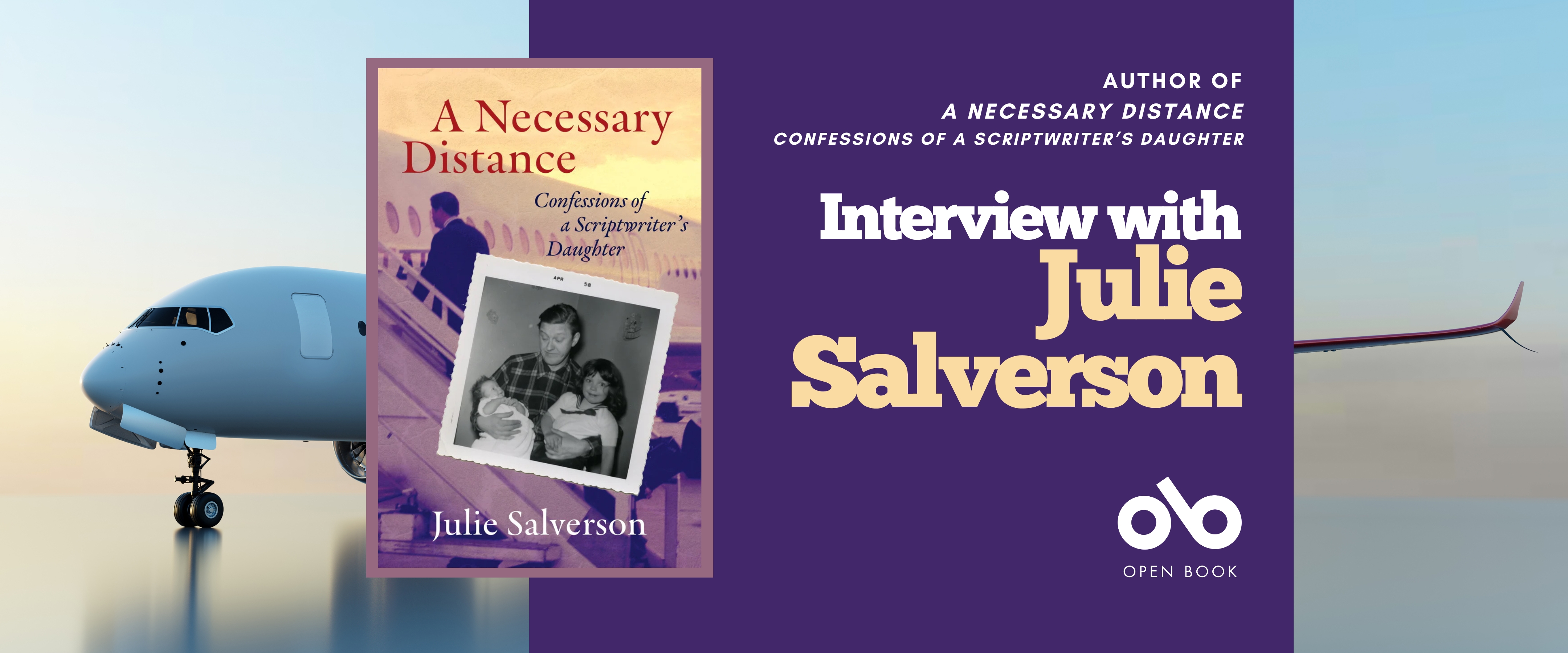

Julie Salverson Takes the Reader on a Fascinating Journey Through Her Father's Life in A Necessary Distance

A multi-faceted creative, Julie Salverson has left a significant literary footprint over the course of her career, working as a nonfiction writer, playwright, editor, scholar and theatre animator. The author has never shied away from explorations of important sociopolitical issues, nor from interpersonal stories with true humanity and empathy.

In her new memoir A Necessary Distance (Wolsak & Wynn), Salverson delves into the deeply personal account of her father, George Salverson, and his storied career as a writer of radio plays for the CBC, and later as their first television drama editor. He kept very little of his work, however seminal it proved to be in Canadian TV, and it was years later that Julie found a series of notebooks that her father kept while working on a 1960s documentary about world hunger. Only then did she realize her father was not the man she thought she knew.

This fascinating work of nonfiction gets to the heart of a very specific personal and political history, and a moment in time where one unique man was caught in a time of great change.

Learn more about this riveting work in our True Story Nonfiction Interview with the author, which we're delighted to share with our readers today on Open Book!

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Julie Salverson:

It is a wonderful thing to have a legacy of stories. Personally, but also as communities and as a country, we need to face and claim our inheritance. My father died in 2005 and it took me five years to get up the nerve to open the very few boxes he left behind. I was focused on the loss, not what there was to inherit. Finally, a friend said, “I am coming over with files and markers and helping you sort!” I found something I didn’t know existed – seven small black hand-written notebooks that were his personal account of a trip around the world in 1963 to make a documentary on world hunger. I couldn’t believe it – including Japan, Indonesia, India, Ghana, Benin, Kenya, Brazil, Peru, Mexico. Ten weeks. Three men – director Gene Lawrence, cinematographer Grahame Woods, and my dad the writer. Flying in small planes, during the cold war, no internet, no phones, hardly receiving mail from home. And a daunting task – in a thirty-minute documentary, tell a global story of how small communities are tackling the problem of hunger, and succeeding. The film was sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, in response to a call by American President John F. Kennedy for a ‘year to end world hunger’.

It was also an unexpected surprise to discover my father’s huge role in early CBC history and what CBC radio meant to people in Canada. I really don’t want this history to be lost! In 1946 only 16.3% of people had telephones, and those were mostly in cities. All the rest had for connection was the radio. Dad wrote early radio drama, a weekly series called CBC Stages that was broadcast live. My dad was also the first tv drama editor for CBC. As I wrote, I also learned about my grandmother, Laura Goodman Salverson. I knew she was the first woman to win the Governor General’s Award, and won it twice (1937, 1939) but I didn’t know how much scholarship there was about her or that she wrote consistently about women and poverty, about the situation of immigrants – she wrote the first novel in English about non-English immigrants, the Icelanders. In fact, her GG winning autobiography is called Confessions of an Immigrant's Daughter – hence my subtitle.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

JS:

My father was telling stories of communities addressing famine, lack of food. I started the book asking, “What is the planet hungry for now?” Food and water are still huge issues (particularly water) but what is sustenance at the deepest level? As I answer this question, I realize that A Necessary Distance addressed that, without realizing it! The book is about how we draw on everything we have, in order to move forward with, I’d say, a kind of radical sense of possibility. I think the planet is hungry to access and mobilize all that has been learned that is generative – we are hungry for our inheritance.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In this historical moment all of us our needed to save the planet. That means facing our connections to past wrongs, but also claiming the resources and teachings and above all the stories that can help us move forward. What inheritance can we claim that is generative, not destructive? Shame is not sustainable. Knowledge is.

My publisher Noelle Allen wrote me a note early on: “For Canadians, it is hard to face the skeletons in our closets”. As a white person I am part of colonialism, and I need to tease out the threads of this, understand the damage I inherit but also the possibilities. I have my father’s documentaries, his dramas and my grandmother’s books and essays about immigrants and justice. I have my mother’s passionate caring. I have Icelandic stories about how to live, about what is alive in trees and rivers and lakes, about independence from colonizers. Tim Lilburn says that many of us with European heritage feel restlessness and rootlessness because of our detachment from Western wisdom traditions that could teach us how to live “undivided from one’s earth.” He says this happened to our ancestors long before they left Europe.

I think we all need to dig, listen, seek out anything in our own traditions – not only blood, that is too essentializing for me – also teachers, stories, what we have read from the past, including the wandering paths of our ancestors. Look for any glimpse of help that reminds us how to listen and look and be. That is what I did in this encounter with my father and my histories – attempted to shape a story from the pieces, to go forward.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

JS:

Two things are constant in my writing: I write from inside the experience of learning something, so I tell the ‘outside’ stories and the ‘inside’ stories – I write the encounter. Most of my work – plays, opera, essays, books - are about what it is to be a witness to violence, to trauma and difficulty in the world, while still embracing beauty and life. I retired from Queen’s Drama Department in Kingston last June, but for over twenty years I taught a course called Theatre as Witness – how do we as artists pass on stories of violence, risky stories. And how do we do that without reducing people to victims, heroes or villains, but see their complexity, their agency and their failures. How do we see their joy, not only their pain. This is the most important thing to me.

In this case, I’m witness to my father. How do I portray this 46-year-old white man who had never been outside North America, and allow his ignorance and his bravery? His struggling with how overcome and exhilarated he was by everything he encountered, and his openness, his willingness to learn, his deep humanity.

I decided to write the experience of reading the journals because that encounter – being a vulnerable observer – interested me. I didn’t know what I would find. I wrote my way through surprises, delights, grief, all of it about my family and about the world, then and now. As I wrote, I researched what was going on in the countries he visited, the politics, the tensions between America and Russia (this was the heart of the cold war), liberation movements and independence from colonial rule. It was all fascinating and sometimes brutally sobering. For example, I learned about something called The Djakarta Method, which was a way imperial nations (America, England, Portugal, Holland) collaborated with local people, helped promote them, and organized the overthrow of developing independence movements – this is well documented in the book The Djakarta Method (Vincent Bevins) and was used in Chile, Nicaragua, Indonesia and many other countries.)

Learning about the specific historical moments dad moved through in 1963 was a fascinating part of my process writing the book. I weave these stories in, often reconstructing conversations and scenes from Dad’s notes – using my experience as a dramatist and playwright. His voice is full of stories because he was a natural storyteller and learned it at his mother’s knee.

OB:

Do you remember the first moment you began to consider writing this book? Was there an inciting incident that kicked off the process for you?

JS:

In 2016 I published Line of Flight: An Atomic Memoir, in which I follow the history and stories of uranium from Great Bear Lake, Northwest Territories, to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima in 1945, while exploring my own ‘atomic childhood’ and obsession with safety and nuclear war. That was a kind of travel memoir, interconnecting my personal stories with the stories of uranium and the bomb and atomic culture. When I found these notebooks, my husband Bill said, “Well, here’s your next trip and your next book!” It was immediately a good idea.

OB:

Did you write this book in the order it appears for readers? If not, how did it come together during the writing process?

JS:

I kind of did write it in the order it appears. I decided not to read the notebooks through and then write – instead, I wrote the encounter. So it is chronological, through the pandemic and lockdown, through the 2016 American election, these things progress with the book. There was a lot more what I call “covid diary” in the book but I cut it out. I needed it to write, but it wasn’t essential. Because I write everything happening inside and outside me AS I write, I have to be a pretty brutal editor. I was helped a lot by Noelle Allen and also a close friend who scrutinized the manuscript, Vera de Jong.

_________________________________

Julie Salverson is a nonfiction writer, playwright, editor, scholar and theatre animator. She is a fourth-generation Icelandic Canadian writer: her father George wrote early CBC radio and television drama and her grandmother Laura won two Governor General Awards (1937, 1939). Julie's theatre, opera, books and essays embrace the relationship of imagination and foolish witness to risky stories and trauma. She works on atomic culture, community-engaged theatre and the place of the foolish witness in social, political and inter-personal generative relationships. Salverson offers resiliency and peer-support workshops to communities dealing with trauma and has many years of experience teaching and running workshops. Recent publications include the book When Words Sing: Seven Canadian Libretti (Playwrights Canada Press, 2021) and Lines of Flight: An Atomic Memoir (Wolsak & Wynn, 2016).