Karl Kessler & Sunshine Chen Honour Waterloo's Vanishing Trades with Stunning Portraits in Overtime

From shoemakers to sign painters, felt workers to glove cutters, there are countless skilled, traditional trades and jobs that are slowing disappearing from our increasingly mechanized existence. With that disappearance, we lose knowledge and expertise, often passed down from masters to apprentices generation after generation. And while the disappearance is a quiet one, Karl Kessler and Sunshine Chen don't want it to be unobserved.

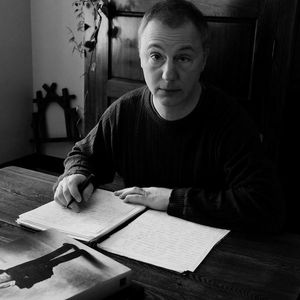

Overtime (Porcupine's Quill) is a unique book, filled with gorgeous black and white portraits of workers in traditional - and vanishing - fields who ply their trades in the Waterloo region. Each portrait is accompanied by an interview, revealing the passion of the skilled workers and artisans and preserving their stories and craft on the page.

We're thrilled to speak with Karl Kessler today about Overtime as part of our Lucky Seven series. He tells us about the love letter to New York that served as a model for Overtime, the idea of "a connection that goes beyond the transactional", and the unexpected realism required to survive as a traditional worker in a changing world.

And if you're in the Waterloo area tonight (November 8), don't miss the chance to attend the launch of Overtime. The event will start at 7:00p.m. (ending at 9:00p.m.) and takes place at Button Factory Arts (25 Regina Street South, Waterloo). The venue is accessible and all are welcome.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Karl Kessler:

Overtime is a collection of fifty black-and-white film portraits plus written profiles of people in Ontario’s Waterloo Region who are among the last of their kind in their trades, professions and other traditions. I wrote the text and did the photography, and based my writing on interviews conducted by my friend and collaborator, Sunshine Chen.

The project spanned from 2008 to 2018. In one way, it grew out of my fascination with the persistence of seemingly anachronistic people, situations and things: ‘holdouts’. This interest stretches far enough into the past that I can’t pin it to one formative or inspirational event. In that way, it feels more like a calling than an interest.

The form of the project was inspired by the work of several documentary photographers down through the ages, most notably Harvey Wang, whose 1990 book Harvey Wang’s New York served as the model for Overtime.

Finally, the inspiration to move beyond imagining it to actually doing it came from Sunshine’s encouragement.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing or did it change during the writing process?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

KK:

So many questions came, and went, and changed during ten years of interviewing, writing and photographing. Boiling them down, they might reduce to something like “People who are in it for the long haul – what keeps them going?”

But bigger than this, what gradually emerged were a few revelations, and these remained constant. Among the most significant has been an insight into what, in the end, people really want. It’s not to have tremendous success in business, or to provide the very best product or service available. Rather, it’s to know other people well, with depth – customers, co-workers, fellow members – and to be known well in return. To make a connection that goes beyond the transactional. When that happens, it’s irresistible.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

KK:

Determining what trades and traditions to seek out meant following long-term cultural trends and media coverage around work, reviewing related material, combing through industrial directories, and listening to experts. It meant tracking change on the ground: driving and walking all over our region, reading commercial signage, and chatting with local aficionados, shopkeepers, customers, business families, workers. And it meant investigating their leads and ideas, and deferring to their expertise whenever it was different from our preconceptions.

It was perhaps unexpected to find that while the people we profiled were frequently philosophical about change, rarely were they nostalgic. They were, almost to a person, clear-eyed realists, which in part might explain how they made it as far as they had.

OB:

What do you need in order to write – in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

KK:

For this project, the writing process was reset with each of the fifty recorded interviews. This was great for establishing some discipline around the work. I listened to each interview twice before writing the one-page profile. First I listened without stops and starts, to learn the voice of the speaker. The second time was slow and incremental, to transcribe information and direct quotes into my notes that would shape the story. After this, the urge to make what I had heard into a vignette was powerful, and so usually I began immediately.

I write sitting at a keyboard, always, and as a result my handwriting has become a picturesque ruin (composing a legible shopping list can be a struggle). Often I write very late in the day, when things are dark and quiet. The world forgets me for a while, and my time is suddenly dispensable. It’s perfect.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

KK:

When my writing feels stuck, or I’m unhappy with it, stepping away from it is usually the only thing that helps. Over-familiarity with a work in progress overloads my ability to assess it, but once my mind is engaged in the outside world, ideas materialize. In other cases, estrangement from a piece of writing helps me begin to forget it, and when I return it looks fresh, and often I can then either determine what isn’t working, or see a new path that has materialized.

OB:

What defines a great work of non-fiction, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.

KK:

As with fiction, my favourite nonfiction delves into small, particular stories to convey something significant that even a far-removed reader will identify with, empathize with, because it contains some broader truth.

Harvey Wang’s New York, the little-known, little book that inspired Overtime, is one of my very favourite books in any category. Straightforward, deceptively simple, full of humanity and deep insight without being saccharine. A masterpiece.

Up in the Old Hotel is a collection of profiles by longtime New Yorker staff writer Joseph Mitchell. In the title piece, Mitchell’s unpretentious, artful language draws me in and makes me feel at home until, as he often does, very subtly he throws a switch and I’m on another track towards a hard, sobering truth.

OB:

What are you working on now?

KK:

I’m touched by the optimism of the question! I’ve been so fully immersed in Overtime for so long that I don’t know what new thing, if anything, will prod me towards another writing project.

Like disengaging in order to un-stick stuck writing, as mentioned above, some unproductive time seems in order. New ideas may come. Meanwhile, I do some writing as part of my work, and I contribute a magazine column about architecture. These keep me in practice – and hopefully not in too comfortable a groove.

_____________________________________

Karl Kessler is a film-and-darkroom photographer originally from New York City. He moved to Ontario in 1996 and currently works as a researcher and writer in the heritage field. With his wife Jane, he coordinates the annual architectural and heritage event Doors Open Waterloo Region. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

Sunshine Chen originally trained in architecture at the University of Waterloo. He now runs Storybuilders Inc., using photo, video and audio to tell the stories and share the experiences of people, places and organizations across Canada. He lives in Canmore, Alberta.