Lucian Childs on Writing a Funny (and Moving) Book about Grief, Trauma, & Queer Coming of Age

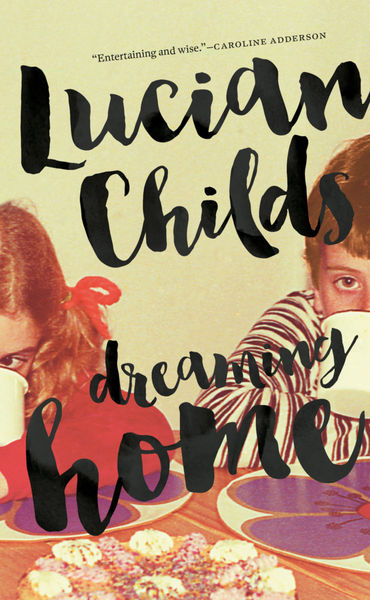

Juggling six different points of view and forty years of cultural history would be an impressive feat for a seasoned novelist, but Lucian Childs managed to pull it off—with style, humour, and pathos—in his debut, the buzzed-about novel-in-linked-stories Dreaming Home (Biblioasis).

A far-ranging tale that ties together AIDs-era San Francisco and the experience of the queer community there with the story of a family fractured by trauma, Dreaming Home is a book that balances skill and heart, with Childs filtering the idea of home in all its glory, pain, and complexity through six unforgettable voices. Kyle, the son at the centre of the novel's family, suffers a serious trauma when an unthinkingly cruel act of his sister's has unintended consequences. Each player in the drama gives their own version of the incident and fallout in the decades that follow. The multiple perspectives enrich and complicate the narrative in nuanced and often even funny ways.

Childs, who is 74, has been publishing short fiction for twenty years, but Dreaming Home is his book-length debut. He's talking to us today about the long ride to Dreaming Home, from the pressure to get 40 years of cultural details spot on (which included keeping track of the technology, music, fashion, and more for every year he wrote in), about his personal connections to the novel's settings, and about how his relationship with his late husband made it possible for him to write the book.

Open Book:

Do you remember how you first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Lucian Childs:

Dreaming Home has an unusual structure and origin story. It is a novel with a unitary overarching narrative—one that tracks the effects of physical and psychological violence, not just on the traumatized central character, Kyle, but on his family and loved ones. Each of the chapters has its own narrative arc as well. So, depending on how you look at it, the book is either a novel comprised of short stories or a linked story collection that feels like a novel.

The stories in the book are based on ones I’d previously published. I began the book in 2008 when I wrote the first lines of the story that is the basis of the novel’s concluding chapter. It wasn’t until the beginning of the Covid lockdown in 2020, though, that I started collecting the tales in book form under the guidance of BC writer, Caroline Adderson (and later the inimitable author, editor and mentor, John Metcalf).

The novel-in-stories allowed me the pleasures of the short story, while deepening the resulting work by giving it a forty-year arc. Each of the stories in the novel is told from a different point-of-view, an approach I feared people would find distancing. So far, the opposite seems to be true. Readers and reviewers say these characters make a vivid and lasting impression. And because the interstices in the stories are merely outlined, they tell me the reading experience feels immersive—since one has to piece together the long arc of the story for oneself.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

LC:

Writing fiction is often an exercise in nostalgia. Dreaming Home is set primarily in Texas and San Francisco, places where I lived for my first forty-three years. We have an expression in the Lone Star State: You can take the boy out of Texas, but you can’t take the Texas out of the boy. And of course, like Tony Bennett and so many others, I left my heart in San Francisco. So, the bulk of the novel is really a love letter to these two extraordinary places and my time there.

This provides narrative advantages as well. In fiction, the stakes need to be high. The soul-crushing effects of parochialism and religious fundamentalism—still powerful factors of Texas life—and the mortality wrought by AIDS in San Francisco at the height of the epidemic, set a powerful tone and give the novel its propulsive feel.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

LC:

When working with Caroline and John to revise my old stories, I wanted to honour their original structure and tone, as a record of where I’ve come from as a writer. Many of the features of the novel’s ending were present in the story on which the final chapter is based. Reimagining Kyle’s sister and capitalizing on new elements I planted earlier in the novel generated an ending that, while very similar in tone to the original short story, is different.

I won’t make the claim one sometimes hears that the ending wrote itself. It required a lot of trial and error. Still, having so many constraints generated the type of conclusion all writers strive for—one that is unexpected, but somehow inevitable.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

LC:

Since I was paying homage to places that were so important to me earlier in my life, I felt duty-bound to get the details right. Over forty years of technology, slang, music, fashion, movies, politics, AIDS treatment and advocacy had to be investigated—in addition to weather, geography, flora and fauna. In particular, the first two chapters in Central Texas required deep research, since one is set on a large U.S. Army base and the other in a conversion therapy program, neither of which I have experienced directly.

Fortunately, I love immersing myself in technicalities, in the mores and speech patterns of the various groups I’m portraying. When writing from outside one’s personal experience, though, it is impossible to completely know the world one is describing. Eventually, you have to resign yourself to that fact and start putting pen to paper anyway, or the research process becomes debilitating.

I’ve been concerned I’ll be called out on details I got wrong—no telephone booths at 18th Street and Castro in 1987, say, or the opening chapter’s Natalie Cole song not having been released when that story takes place. So far, everyone seems to think I nailed it, especially folks who were living in San Francisco in the ’80s and ’90s, the period that takes up over half of the book.

OB:

Did you celebrate finishing your final draft or any other milestones during the writing process? If so, how?

LC:

When Biblioasis sent me printed copies of the book, I had an unboxing party at my apartment with some of my closest friends, who had all listened to me natter on about the project for years. The book having been merely conceptual for so long, I wanted them to help bring it tangibly into the world. I nearly lost it when I read them the section of the acknowledgements thanking them for their patience and support.

The launch event with my friends here in Toronto at Queen Books was also very gratifying. More than half had already read the book and were very invested in the characters and their outcomes.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

LC:

Dreaming Home is dedicated to my husband, Canadian visual artist and author, Alex Turner, who died about a year before I started working on the book with Caroline Adderson. I feel a great affinity for her work and for Lorrie Moore’s—writers who can make you laugh in one sentence, then tear your heart out in the next.

So, while my book is often quite funny, it is at its core a meditation on love, loss, and grief. Without Alex, I never would have deeply understood these emotions. Being in the thick of the grieving process during the writing, these themes worked their way organically into the book. Though tremendously sad, they infuse the work with a deep humanity and viscerally propel it toward its hopeful ending.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

LC:

A carefully chosen epigraph can provide the reader with an entry point for reflection on the overarching themes of the work. In Dreaming Home, I selected a line from John Donne’s famous Meditation XVII, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions—“Affliction is a treasure and scarce any man hath enough of it.”

Dreaming Home explores childhood trauma and its effects on who we are and how we see the world. I believe this process is universal and the specific effects immutable. Fiction often uses the extreme case. Though we may not have experienced a childhood as challenging as Kyle’s, still we are shaped by our own early painful experiences. Donne’s adage transforms the way we look at pain and tasks us to embrace it as the engine in the formation of our innermost selves. This acceptance is central to an understanding of epiphany—that sometimes-maligned literary concept—the sense of arrival toward which, in some form, every work of fiction is driving.

______________________________________

Lucian Childs has been a Peter Taylor Fellow at the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. He is a co-editor of Lambda Literary finalist Building Fires in the Snow: A Collection of Alaska LGBTQ Short Fiction and Poetry. Born in Dallas, Texas, he has lived in Toronto, Ontario, for fifteen years, since 2015 on a permanent basis.