Mike Barnes on the Big Books in His Life, Including One Important "Thundering Masterpiece"

Mike Barnes is one of those rare writers who can do it all – in poetry, short fiction, novels, and memoir, he takes readers on nuanced, brainy, powerfully moving journeys. Fiercely intelligent yet consistently accessible and relatable, Barnes has a unique perspective informed by a deep empathy gained through his own difficult and complex experiences with mental health and grief.

His latest book, Sleep is Now a Foreign Country (Biblioasis), is a deeply personal, thoughtful, unflinching exploration of madness and imagination, delving into an experience in his early 20s which he later understood to be a psychotic break. At the time though, a younger Barnes could only understand what was happening as the looming thing he'd been somehow expecting through much of his young adult life.

Examining what led to that life-changing experience near Munich in 1977, Barnes gently and wisely weaves a story about the dark and often unexplored corners of the mind and what lurks there, for better or worse. The Literary Review of Canada called Sleep is Now a Foreign Country a "bold and singular literary experiment" for "daredevil" readers.

To celebrate this singular new book, we asked Barnes to discuss his reading life and how it has informed his writing. He shared five influential reads, as well as further insight into his reading experiences and predilections, from why he no longer "feel[s] 'should' much any more with reading" and how he can look back and chart his path as a writer through his changing influences over the decades.

The WAR Series: Writers as Readers, with Mike Barnes

The book I have re-read many times:

This is a hard one. There are so many. Each year, re-reading becomes a bigger part of my reading diet. Something I’ve taken to doing a lot in the last few years is re-reading books backwards. Either page by page starting from the last one, or chapter by chapter starting from the last. Back to front, the patterns of the book come into new clarities, and plot points I missed going through the first time finally make sense (very welcome, as plot is something that often confuses me).

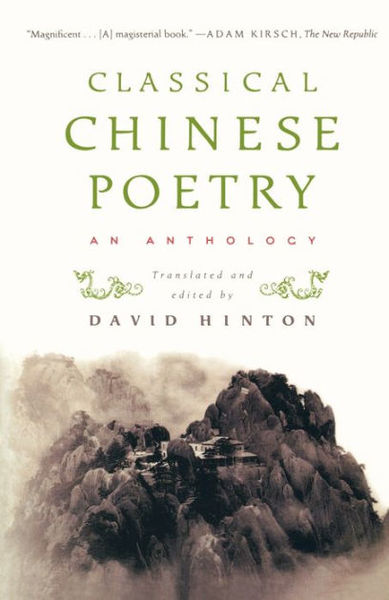

Classical Chinese Poetry, edited and translated by David Hinton, is probably the book I’ve returned to most often in the last ten years. I normally dislike anthologies—they are oppressively large, and I prefer small books—but this one is golden. It spans almost 3,000 years, from about 1500 BCE to 1200 CE or so. It introduced me to some of my all-time favourite poets: T’ao Ch’ien, Meng Hao-jan, Wang Wei, Wang An-shi... I’ve never read an anthology where I was moved to buy individual books by so many of its authors—six so far, and counting, all superbly rendered into English by David Hinton.

These poets accomplish miracles, and they usually do it in four to eight lines. Reading these little gems, I never feel I’m reading something fusty or antique. I feel like I’m encountering ageless wisdom and clarity, a precision of perception that travels effortlessly along on a neighbourhood walk or a trip to the mall or a drive on the 401.

A book I feel like I should have read, but haven't:

I don’t feel “should” much any more with reading. Not in the sense of a “canon” I have to master. I’m a slow reader, but even the fastest reader only dips a toe into the ocean of books. Something that’s addled me more is the authors I’ve wanted to connect with but just couldn’t, or not strongly, even after repeated tries. Chekhov’s been one like this for me. Kafka, too (except for a few of the fables and The Metamorphosis). These haven’t been duty-tries. From what others say of these writers—and from some moments I’ve had with them—they seem like they should be for me. But in the event, they’re not. Not really. Not quite. I’ve felt a bit embarrassed by this, like I’m missing a reading gene. Like people have reserved me a table at a great restaurant I’m sure to like: “it’s made for you.” But each time I go there, tasting conscientiously, recognizing quality and fine flavours—something is missing. I’m pleased, but not delighted. I might be scared to make a no-connect, or part-connect list of writers like this for me, for fear of how long it could stretch. They are the writers that in a parallel life you read and read, because they’re made for you; but in this one, you can only graze each other.

The book I would give my seventeen year old self, if I could:

My first thought is, I wouldn’t give him one, because he wouldn’t read it. He was a passionate reader, with his own fiercely held tastes—and was just beginning to become quite unwell mentally, besides—so he wouldn’t take the suggestion. On the other hand, he loved sci-fi, so he might just be receptive to his future self as Trans-Temporal Librarian. So here goes.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

There are two companion volumes by the same author that I think Mike-17 would likely enjoy, and could really use. If he didn’t love them right away, I think he would be intrigued enough to keep them in his shoulder bag for a few years, until, say, age 24 which was when he found them.

They are both by the great Russian psychologist A.R. Luria. The Mind of a Mnemonist is a true account of a man with almost limitless capacities of memory, whom Luria studied for thirty years without finding an end to his vast recall, shored up by a synesthesia that united each remembered thing across his senses. Yet the subject of this account, whom Luria calls S., is almost unable to think for lack of an ability to generalize and abstract. Like Borges’s “Funes the Memorious,” he can’t make useful categories since he can’t forget differences. For all his gifts, he’s profoundly disabled and leads a stunted, unhappy life. The Man with the Shattered World is almost the exact opposite, telling the story of a bright young engineer, Zazetsky, who suffers a horrible brain injury in the Battle of Stalingrad, robbing him of almost all ability to perceive correctly, to remember, to think. Yet, over the next thirty years, he labours to tell his story, though often able to advance it by only a few words a day, letter by letter, word by word, with the beginnings of sentences vanishing before their midpoints are reached. It’s a superhuman effort—and unfathomably thrilling! His fate is so staggeringly awful, and the tenacity with which he fights his endless battle is just heart-stopping.

In both books, Luria’s narration—especially in the second, where he bridges the engineer’s gaps as co-writer—is unsurpassably lucid and humane.

Mike-17 would be captivated by these complementary studies of the extreme human—I think almost anyone would be—and then, over time, especially after he hit various walls himself, they would resonate even more with their magical capacity to turn inside out, the gift revealing the curse, the curse forcing the spirit’s gifts to shine.

A book I feel strongly influenced me as a writer and why:

I don’t know how it is for other writers, but I seem to find a new influence every few years, someone who hints at a new direction or guides me in a direction I’m already trying to take. Looking back, I can see such a mentor—sometimes a cluster of mentors—for each decade or so. A book that helped me in my mid-twenties, when I was starting to write a great deal, was Journey to the End of the Night, by Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

It staggered me. I read and re-read it, taking down so many of its phrases and images that my notebook became a mini-Journey. I think what Céline offered me as a budding writer was permission to be wild in metaphor. The freedom of a loosened brain-case. Later, Céline devolved into a hateful crank spouting anti-Semitic rants and repeating stale echoes of himself. But this first book is, as Kurt Vonnegut Jr. once described it, “a thundering masterpiece.” André Gide once said, of Céline, that Céline wrote not of reality but of the hallucinations reality provokes. I was very heartened to be told that hallucinations could be more than symptomatic, that in the right hands, they might even be art.

The best book I read in the past six months:

The White People, by Arthur Machen, was astounding. Published in 1904 (though probably written in the 1890s), it tells, after a brief conversation on the nature of evil, of a young girl’s gradual entry into a supernatural realm of deeply strange beings inhabiting the world alongside humans, their nature and intentions quite inscrutable.

The bulk of the novella is the girl’s own diary, and her adolescent voice is entirely convincing, the sense of her straying farther and farther into a deviant world quite terrifying. After reading it, I walked around in a daze for some hours or even longer—as if waking from a particularly bruising dream.

The commonly used literary trope that ruins a book for me:

I can’t think of one. There are things I dislike encountering, but these don’t have the power to completely ruin a trip that is offering substantial pleasures. Books are large vessels, and don’t need to be leak-proof to take you somewhere enjoyable. They do need robustness of some sort—e.g. story, language, ideas—but if they have one or more of these, they can survive a lot of holes without capsizing. I’ve never understood the flaw-collector type of reader. They remind me of those people who leave a six-course banquet and harp on one overly spicy appetizer or a side dish that was bland. Listening, you can wonder if they actually like food.

__________________________________________________________

Mike Barnes, a dual Canadian-American citizen, has published eleven books across a range of genres: poetry, short fiction, novels, and memoir. His last nonfiction book, Be With: Letters to a Caregiver, has been praised by Margaret Atwood as "Timely, lyrical, tough, accurate." Born in Rochester, Minnesota, he lives in Toronto.