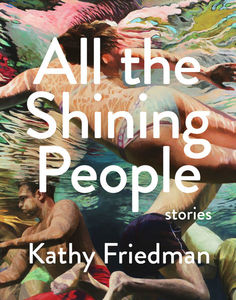

"Our Stories Will Still Be There" Kathy Friedman on Processing Complex Personal & Political History in Her Debut Short Story Collection

A life drawing model, a former political prisoner, a man unpacking his father's complex legacy—the fascinating characters in Kathy Friedman's debut short fiction collection, All the Shining People (House of Anansi Press, forthcoming April 2022), are varied and unique, but linked together by their Jewish South African community in Toronto and their experiences navigating a new home and country.

Each one is grappling with their roots, their complicated longing for home, and their culture, all while experiencing the universal trials of love, loss, and identity. These twelve stories hail a bright new voice in CanLit, expertly teasing out the deep and achingly human experience of feeling like an outsider. Friedman herself emigrated with her family from South Africa to the suburbs of Toronto when she was five, going on to become a creative writing instructor at the University of Guelph and the co-founder of Inkwell Workshops, a series of writing workshops serving writers living with mental health issues, trauma, or addiction.

We're excited to speak with Kathy today about All the Shining People as part of our Keep It Short series for short story writers. She tells us about the question that sparked all the stories in the collection, shares a story of the incredible generosity she encountered during her research trip to South Africa, and notes the acclaimed story collections focused on immigrant identity that she read to inspire her own writing journey.

Open Book:

What do the stories have in common? Do you see a link between them, either structurally or thematically?

Kathy Friedman:

I wrote these stories to explore my Jewish, South African identity. Most are linked structurally, with characters in one story usually showing up in another, and all are linked thematically around issues of identity, home, belonging, connection, and loss.

OB:

What do you enjoy most about writing short fiction? What is the toughest part?

KF:

I love doing research. It’s so cool to find a topic that fascinates me and go down a rabbit hole to learn about it. For me, the toughest part of writing short fiction is the first draft. Once I have something down on paper, I can work to shape it, but getting to that point can be a real slog.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for any of your stories? Tell us a bit about that process.

KF:

All the Shining People began with the question: Who am I? I left South Africa just before I turned five, meaning I spent the most formative years of my life in a brutal society where White supremacy was legally codified. I didn’t know how to begin thinking or writing about this, so I turned to books. I read South African history as well as fiction and memoir by apartheid-era Jewish writers and Black writers. I also read parts of South Africa’s harrowing Truth and Reconciliation report.

I did targeted research as well for each story in the collection. In some cases, my research was pretty low-key: for example, to write one of the first scenes in the book, I asked my dad to explain to me, in detail, how he used to shave in the 1980s. For other stories, the process was a lot more involved: I travelled to South Africa, where I did library and archival research, conducted interviews, asked the names of plants and birds, and recorded overheard dialogue. I returned from that month-long trip and typed up seventy pages of notes. Since it wasn’t possible for me to return to Israel/Palestine, I read blogs about Birthright trips and watched Birthright-related YouTube videos as well as movies set there.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

KF:

When I visited Durban’s Cato Manor Heritage Centre, I got to chatting with the security guard. I told her that I was researching the devastating forced removals that took place in Umkhumbane (or Cato Manor) in the early 1960s as a result of apartheid laws. This woman, Sebenzile, offered to speak to the museum’s curator and see if they could find an elder who’d lived through the removals to talk to me.

A former actress who lived nearby agreed to the interview at her home. Sebenzile actually drove me and a friend there: apparently it was a rough area, and she was worried we wouldn’t be safe going on our own. It was a beautiful day, and we sat on Lorraine’s small lawn in the sunshine and asked questions about her fascinating life. Her stories about Umkhumbane were painful, but she told each of them with a joke. She showed us old photo albums and a headdress that had belonged to her grandmother, who was a sangoma, or traditional healer. To be welcomed into someone’s home, into someone’s life like this—the generosity was breathtaking.

OB:

What story collections were you reading for inspiration while writing your book? What did you learn from them?

KF:

From reading David Bezmozgis’s Natasha, Junot Díaz’s Drown, and Ayelet Tsabari’s The Best Place on Earth, I learned ways to write about hybrid, immigrant identities that felt fresh and alive to me. These books also really inspired me on the level of language, and I wanted to capture the South African English, infused with Yiddish and Hebrew expressions, that I grew up speaking with my family. Twilight of the Superheroes by Deborah Eisenberg and Whites by Norman Rush helped me write smarter, more politicized fictional characters. And Ehud Havazelet’s gorgeous collection Like Never Before inspired me to write about a family from different perspectives while moving through time with them. Also, the first story in my collection was heavily influenced by Bruno Shulz’s The Street of Crocodiles, and I wrote the second story in response to Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior.

OB:

What if, anything, did you learn from writing these stories?

KF:

This book took me ages to write, and that process was really tough at times. I think the main thing I learned from writing these stories is to trust myself and my own creative process a bit more. And to step away from the work as often as needed. We don’t have to write every day, every week, or every month. Our stories will still be there when we’re ready to return to them.

_______________________________________

Kathy Friedman emigrated with her family from South Africa to the suburbs of Toronto when she was five. She studied creative writing at the University of British Columbia and the University of Guelph, and was a finalist for the Writers’ Trust Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Grain, Geist, PRISM international, Canadian Notes & Queries, and the New Quarterly. She teaches creative writing at the University of Guelph and is the co-founder and artistic director of InkWell Workshops. Kathy Friedman lives in Toronto.