Read an Excerpt from Eyes of the Rigel, Booker-Nominated Roy Jacobsen's Haunting Story of a Woman's Postwar Journey

In Europe, the end of the Second World War officially meant peace, but that peace was for many a deeply uneasy one. Collaborators and resistance fighters lived side by side, with communists, refugees, former military, and others each carrying their own complex experiences of the war. Distrust, trauma, and rage simmered under the surface of a stunned continent.

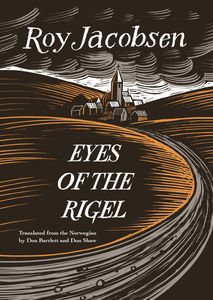

It's into this tense environment that Ingrid Barrøy wanders with her 10-month old child in Eyes of the Rigel (Biblioasis, translated by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw) by Roy Jacobsen. First introduced in Jacobsen's Booker Prize-shortlisted The Unseen (and featured again in its acclaimed sequel, White Shadow), Ingrid returns in this, the third novel in the series, finally leaving—for the first time in her life—the tiny Norwegian island of her birth, which shares her surname.

Barrøy Island was largely untouched by the war, apart from the nearby sinking of the MS Rigel, a German ship carrying POWs. A prisoner named Alexander made it to Barrøy alive, only to be found by Ingrid, who fell in love with him and hid him. One he was strong enough, he left to seek safety in neutral Sweden, leaving Ingrid with a newborn daughter and a note in a language she cannot read.

As Ingrid attempts to follow her lover's journey so they can reunite as planned, she gets a crash course in all that she has missed. Her island's level of isolation means she's never so much as taken a train before. As she travels, meeting strangers both kind and cruel, many damaged in various ways by the war she witnessed from afar, she is forced to ask difficult questions about herself, Alexander, and her view of the world. Called "remarkable" by The Guardian, Eyes of the Rigel is a triumph of fearless storytelling and intense examination of the human condition. We're excited to share an excerpt from the novel here today, courtesy of Biblioasis.

Excerpt from Eyes of the Rigel by Roy Jacobsen, translated by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw

PROLOGUE

From the sky, Barrøy resembles a footprint in the sea, with some mutilated toes pointing west. Except that no-one has ever seen Barrøy from the sky, other than the bomber crews, who did not know what they were seeing, and the Lord God, who does not appear to have had any purpose with this imprint He has left in the sea.

Snow is now falling heavily on the island, making it white and round – this lasts for one day and a night. Then its inhabitants will begin to form a black grid of tracks criss-crossing the whiteness, the widest of them will connect the two farmhouses, the old, run-down building on the island’s highest point, surrounded by a cluster of trees, and the new one in Karvika, which is resplendent and showy, and in the summer is reminiscent of a stranded ark.

Then paths will appear between the farmhouses and the barn and the wharf buildings and boathouse and peat-stacks and potato cellars and haylofts and moorings, between the islanders’ workplaces and stores, paths that will become entwined into a tangle of wild, random squiggles, the marks of children and play and ephemerae; there are many youngsters on the island in this, the first year of peace, there have never been more.

And then a dirty-brown rivulet winds its way south-west through the landscape, it is the sheep going to graze on the seaweed in the south of the island. Barbro hobbles along behind them, wielding a pitchfork and singing at the top of her voice, her face turned to meet the dancing snowflakes, which she snaps at between the strains of her song.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

One might speculate about why she doesn’t drive the animals down between the new wharf building and the Swedes’ boathouse, the shortest distance between the barn and the sea. But Barbro knows what she is doing, it is late winter and the seaweed is in the south, knotted together by storms and driving rain into brownish-black ropes, and left in coils at the highest point of the tide, where it lies, rank and covered in ice.

Barbro shuffles back and forth, pulling the strands apart so that the animals can get to the semi-frozen sustenance they contain, she is soon hot and sweaty and sits on the tree trunk they found drifting here a lifetime ago and secured with pegs and lines hoping that one day it would be worth something. And she begins to ask herself whether they have too many sheep this year, whether these undernourished creatures will manage to carry their lambs through to April and May, at this time of year she always frets about these things – every season has its worries, even the summer, when it can rain for months on end.

But then she feels a stinging sensation behind her left ear, it extends down the back of her neck, into her shoulder, along the arm that is resting on the tree trunk and into her hand. A hot, inner stream flows from Barbro’s head and starts to drip from her longest finger, which immediately stiffens and creaks, as if made of glass.

She opens her eyes and realises that she is lying on her back, the snowflakes are falling on her eyes, she blinks and sees that Lea, the sheep, is standing at her side, staring out to sea, now whiter than ever, it is as calm as milk, there are no birds, except for the three cormorants sitting on the skerry to which they have given their name, and not even they are making any sound.

Barbro digs her fingers into Lea’s wet fleece and drags herself to her feet. The other sheep stand watching. She picks up the pitchfork, feels a protracted stab of pain pass through her waist, and herds the flock in front of her up the same track, to the marsh pond where they cut peat in the summer. She knocks a hole in the ice crust so that the animals can drink, and one by one they waddle up the slope unprompted and disappear into the barn.

Finally Barbro sets off, her right hand still buried in Lea’s wool, and she doesn’t let go until this sheep, too, is swallowed up by the darkness. She bolts the door behind her and stands with her gaze fixed on the farmhouse, but fails to see the hand waving in the kitchen window. Barbro turns and follows the path leading to the new wharf house, goes into the baiting shed and stares down at the three holes in the bottom of an empty line-tub as the wind rattles a loose board in the south-facing wall. She sits down, grabs a bodkin and twine, and her hands set about making netting. The door opens and a voice asks what she is sitting here for.

“Aren’t tha freezen?”

It is Ingrid, who had seen her aunt from the kitchen window and wondered why after going down to the quay, which Barbro often does, she hadn’t come back up to the house today, and a long time had passed, evening was drawing in.

Barbro turns and fixes her with an intent gaze, and asks:

“Who ar tha?”

Ingrid moves closer and peers at her, tucks a few strands of hair under her headscarf and realises that she will have to answer this absurd question truthfully, and at great length.

1

It is summer on Barrøy, 1946, the down has been gathered, the eggs are in barrels, the fish have been collected from the racks and weighed and tied, the potatoes have been planted, the lambs are gambolling in the Acres, and the calves have been weaned from their mothers. The peat has to be cut, and the old house needs painting so it has no cause to feel ashamed beside the new one. From the hill behind the barn, Ingrid Barrøy is watching the boat in the bay, a cloud of terns above it, it is a whale catcher, the Salthammer, which they acquired when the previous owner went bankrupt, the Barrøyers have become whalers.

The Salthammer has a harpoon cannon on the bow and, on the mast, a white crow’s nest with a black ring around its middle, it has rigging like a sailing ship and a wheel atop the wheelhouse roof, encircled by a white tarpaulin, there is a bait house and a modern line-setter, it is an imposing vessel for all seasons and occasions. Ingrid can hear the sound of hammering and sees Lars and Felix making preparations for the first whale hunt, small boys running to and fro along the deck, she can hear their voices rising and falling from across the water, and Kaja is sleeping on her back in a shawl.

Then her daughter wakes up. Ingrid unwraps her and lets her crawl about in the heather to her heart’s content, and is startled at the sight of her jet-black eyes, takes her into her arms and walks down the hill towards the garden, where the soft-fruit bushes have begun to bud. She sits on the well-cover next to the newly purchased tub of paint and brushes, there are so many things that have to be done on the island, it has never had a brighter future, it has never had so many inhabitants, and it is no longer hers.

Ingrid goes into the kitchen and places Kaja on Barbro’s lap, walks down to the shore and rows the færing out to the Salthammer, waits until Lars looks over the gunwale and asks whether she has brought him some coffee.

Ingrid says they have coffee on board, don’t they.

Lars laughs and tells her they have managed to find a harpooner and will pick him up in Træna in a week, weather permitting.

Ingrid rests on the oars and says she will be rowing over to Adolf ’s in Malvika with the young’un, this evening, in the færing.

Lars asks what she wants to see Adolf about.

Ingrid shrugs, Lars says it’s no skin off his nose, they’ve got enough boats.

To Ingrid this seems a rather high-handed attitude regarding the island’s assets, so she says she is going to be away for a while.

“Ar tha now?”

The small boys come to the railing, too, Hans and Martin and, behind them, lanky Fredrik, who in the course of the winter has grown taller than is good for him. They spot Ingrid, immediately lose interest, and pester Lars to be allowed to shoot the harpoon, they can practise on some old fish crates they have seen on the shore, can’t they.

Lars laughs and lifts up three-year-old Oskar so that he too can look down at Ingrid, who waves to him. Then Felix also appears, clutching some cotton waste between his oil-blackened fingers – such that all Barrøy’s men, both big and small, are standing in line on the deck of the island’s economic future, like an unsuspecting farewell committee, as Ingrid Marie Barrøy lays into the oars and rows back ashore, relieved that this has been much easier than she had feared.

She walks up to the house and also tells Barbro and Suzanne that she is going away for a while, casually dropping the news as if it were an everyday matter. But here in this women’s world it turns into something rather more serious than it ought to be. Barbro has questions about where she is planning to go, why, and for how long? While Suzanne understands what is afoot and remarks contemptuously that Ingrid is lucky to have someone to miss, to search for, then hurries out to hang the washing on the drying rack.

Ingrid packs the small suitcase she takes with her whenever she tries to leave the island. And after she has gone down to the shore and wrapped Kaja up inside the canvas bag and settled her on the sheepskins at the back of the færing, before putting the suitcase in the forepeak, there is only Barbro, now transformed, who has a sense of the gravity of the situation, she stands and says goodbye with her arms crossed, her dress is sky blue, newly acquired with the proceeds of the winter, it is covered with huge white flowers, she says:

“We war goen t’ paint th’ hus, warn’t we?”

“A’m not stoppen thas.”

Barbro fidgets uneasily and says it’s not possible to paint a house without Ingrid. Ingrid laughs and says they can wait until she gets back then.

“Reit,” Barbro says. “An’ hvan will tha bi comen bak than?”

“It’ll bi some taim.”

“Some taim,” Barbro repeats, standing on the shore, in such a huff, as Ingrid manoeuvres the boat around Nordnæset, that she can’t bring herself to wave until it is too late. By then the sun is in the north, low and white, and beneath it lies the sea, like a grey stone floor.

_____________________________________________________

Excerpt taken from Eyes of the Rigel by Roy Jacobsen, translated into English by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw. Published by Biblioasis. Copyright by Roy Jacobsen, 2022.

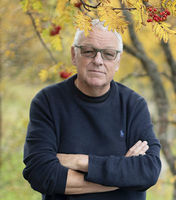

Born in Oslo to a family that came from northern Norway, Roy Jacobsen has twice been nominated for the Nordic Council’s Literary Award. He is the author of more than fifteen novels and is a member of the Norwegian Academy for Language and Literature. In 2009 he was shortlisted for the Dublin Impac Award for his novel The Burnt-Out Town of Miracles. Another novel, Child Wonder, won the Norwegian Booksellers’ Prize and was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection. The Unseen, the first of a series of novels about Ingrid and her family, was a phenomenal bestseller in Norway and was shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize and the 2018 International Dublin Literary Award, selected as a 2020 Indie Next pick in North America, and named a New York Times New and Noteworthy book. White Shadow, the second Barrøy novel, was published in North America by Biblioasis in 2021.