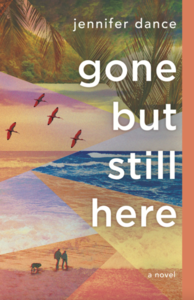

Read an Excerpt from Jennifer Dance's Gone But Still Here, a Story of Loss, Memory, & Family

Writer Jennifer Dance has worked in anti-racism activism and awareness through her fiction and theatre work for decades. Her newest book explores an interracial relationship through a new lens, and one that has become close to her heart through personal experience as she cares for a partner living with Alzheimer’s.

Gone But Still Here (Dundun Press) tells the story of Mary, whose memory is fading by the day. As her dementia advances, she becomes increasing desperate to hold memories of her complicated past close, racing against time to write a memoir of the interracial love story that shaped her life more than 40 years ago.

When Mary is forced to move into her daughter Kayla's house, Kayla finds herself caught between her fading mother and her sullen teenage son. The dynamics between the two women, Mary's elusive memories, and even the household pets become complicated by decades of unspoken and unresolved family tensions.

By turns heartbreaking and ruefully funny, relatable and illuminating, Gone But Still Here is a powerful story of family, love, memory, and self. We're proud to present an excerpt here today courtesy of Dundurn Press, in which we meet Mary as she attempts to find where her story begins.

Excerpt from Jennifer Dance's Gone But Still Here:

january 2019: four months earlier

mary

I wonder how my life might have turned out if Keith had not sat at the desk next to mine on that first day of chemistry class. Easier? Perhaps. Duller? For sure. I had no idea of the saga that our meeting would ultimately create. But that day at university, I was smitten — with his broad, bright smile and his enormous dark eyes flanked with eyelashes so long that they grazed the lenses of his trendy Aviator shades. And I stayed smitten. Always.

Reading the words aloud, as a writer should, my voice quivers and tears sting my eyes. It takes me by surprise. I haven’t cried for decades — not even when my mother died.

Although, when Paco passed away, I bawled my heart out in a dreadful expression of grief that was disproportionate to the life of a little black cat. Looking back, something was going on there: grief for Keith and my mother spewing out from some unfathomably deep place as I rocked the dying cat in my arms.

Crap. Writing a book about Keith is going to be harder than I thought. It was supposed to be easy. No convoluted plot or creative characters. Just me telling my story for our children, so they can learn about their father. It’s not that I deliberately kept secrets about him. But it was painful to talk about. So I pushed it aside. Pushed him aside.

I stare at the backs of my hands, draped on the keyboard... pale skin flecked with brown age spots and crisscrossed with blue-green veins. They belong to someone old, not to me. But the wedding band on my fourth finger is comfortingly familiar. The gold is worn thin. I twirl it, trying to figure it all out.

“You still wear my ring,” a voice says, warm and lyrical, with the trace of laughter.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Until recently, I thought I’d forgotten the sound of Keith’s voice. He died before the era of answering machines or cellphone recordings, and I wasn’t able to recall his voice even when I wanted to. I’d forgotten him! It had been deliberate... my way of surviving, because the grief was like quicksand, waiting to pull me under if I stepped too close. I had to keep my feet on solid ground for the sake of the children. I had to get out of bed and change diapers and feed them. I had to be the best mother I could be. They’d lost their daddy; they couldn’t lose me, too.

But the kids are all grown up now. They never come to see me. Or phone me. Though they swear they do. How come my children turned out to be such big liars?

Keith speaks to me again. “Write about me. About us.”

He sounds so close, so real that I can’t stop myself from snuggling into the thought of him. But I know my mind is just playing tricks. Keith is gone. I want to bring him back, though, capture him in words on the page and give him immortality. But I don’t want to go through the pain again.

I pull myself together, forging on in a well-practised technique taught to me at an early age by my stiff-upper-lip parents. I can still hear their words. “No point crying over spilled milk; there’s always someone with a bigger problem than yours; and think of all the starving children in Africa.”

Focusing on the screen, I read the first line again.

I wonder how my life might have turned out if Keith had not sat at the desk next to mine...

“Life can turn on a dime,” I say aloud, feeling uncommonly wise yet morose. “One fork in the road — right or left — and everything changes. Meeting Keith all those years ago was the major fork in my life. My story should start there. But not today. My emotions are too fragile. I want to write about things that make me happy, not sad.”

“Start with going to Trinidad then,” Keith says, “that was the first of those life-changing forks in the road. That’s where you should start your story.”

In my mind, I lean against the ship’s railing, yelling goodbye to my school friends on the wharf. It’s 1966, a summer day. I’m seventeen years old, and the Beach Boys sing a Bahamian folk song in my head: “So h’ist up the John B. sails / see how the mainsail set / send for the captain a-shore / let us go home.”

I start to type.

__________________________________________________

Jennifer Dance is an award-winning and bestselling author, playwright, and composer. She is also caregiver for her second life partner, who is journeying through the decline of Alzheimer’s. Jennifer lives on a small farm in Stouffville, Ontario.