Read an Excerpt from NIGHT TERMINUS, the Debut Novel From Ellis Scott

Acclaimed short story writer Ellis Scott has arrived with a haunting debut novel that traces queer survival, memory, and love across borders and decades in the shadow of the AIDS crisis.

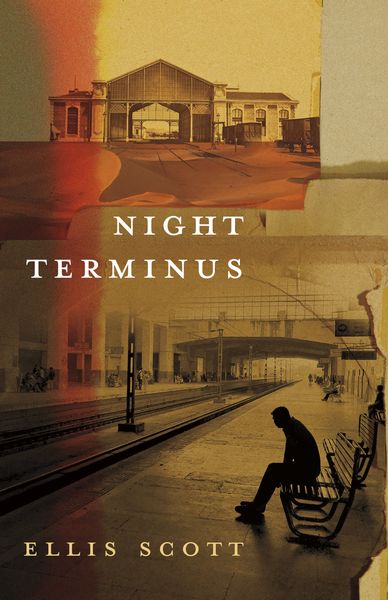

Night Terminus (Dundurn Press) begins with a chance encounter in 1985 and follows an unnamed narrator over forty years of movement and reckoning. From Paris to Montreal, across a divided Europe, into the Iranian desert, and finally to Provence, his life unfolds through intense, fleeting, and enduring relationships with men shaped by exile, illness, artistry, and desire.

Each place brings a new figure into focus: a troubled lover, a determined companion, a found family bound by care and loss. As the journey stretches across continents and time, the novel bears witness to a generation marked by one of the most devastating health crises of the twentieth century. Lyrical and elegiac, the book is a record of what was lost and a tribute to those who survived and remember.

Check out this special preview excerpt of this gripping novel, featured in advance of it's February 3rd release (and you can pre-order right now!):

An Excerpt from NIGHT TERMINUS by Ellis Scott

Chapter One: Louis Korol

Toward the end of February 1985, after being released from Maudsley Hospital, I took the National Express overnight bus from London Victoria to Dover on my way to France. I snagged a ticket for one pound using my dead friend’s coach card, which thankfully had eight months left on it, hoping to catch the 3:00 a.m. Sealink ferry to Calais port and the train from Calais Ville station to disembark in Paris before noon. I had buried seven friends that year and there were still ten months to go.

Well after noon, my train pulled into Gare du Nord station. I slept for most of the journey to Paris, only waking up to the jerking carriage movements as we slowed, and for reasons unknown to me, had dreamt of the night before, walking to the ferry terminal from Dover-Pencester coach station. I turned into the briny air of Marine Parade and the floodlights of the ferry dock were to my left, past low-rise blocks of flats that lined the shore of the otherwise characterless promenade and had only gone fifty metres when I came upon a bronze statue of a man on a marble plinth at the centre of a wide, bare lawn. He wore a double-breasted Mariner’s coat and tall boots, ready to head off to sea, with a pronounced lean on one leg so that the side of his pelvis dropped below the other, giving him a very provocative bearing. The name on the inscription plate was CHARLES STEWART ROLLS, which rang no bell in my mind. I thought it jaunty that the sculptor had given him white epaulettes, then realized that pigeon droppings covered his shoulders. The smooth, round face, neck forward with intent, stared out over the water from its vantage point at an unseen object or historical event, and I followed its gaze, floating out over an inky sea until I was shaken awake.

A sneaker shoelace had inexplicably come undone as I slumbered. I walked to the exit in the damp air, alighting in no particular hurry, allowing most of the other riders to pass. Looking up at the train shed while walking, admiring the station’s fine, decorative skeleton of deep-green wrought-iron pillars that butterflied to meet their girders, I almost ran into a cleaner, head bowed as she swept the platform, wearing a light blue apron uniform over her street clothes. When I apologized in English, she glanced at me, grimaced, and went back to work. I scouted for a place to sleep later, either near the platforms, which were safest after midnight, or by the departures board in the entrance hall, where it was busiest. One counted on a few dozen backpackers to assemble after dinner and everyone slept close together. Fast-food bags and dirty socks had been left in the corner at the head of the first platform. Empty walls stretched between exit doors to sleep against, just in case, so no one could approach from behind and steal your belongings. The main hall was quiet except for a woman’s voice echoing over the loudspeaker, and barren for its cavernous size, save for a small café and boulangerie, a newsstand by a cork noticeboard, and two long, glassed-in counters on both sides of the trellised departures board facing the street entrance. The left sign said BILLETS GRANDES LIGNES in blue neon and the right said RESERVATION INFORMATION in white, both in the same italicized art deco font. A pigeon sprinted for the exit.

As I paced back and forth, scanning the room, I saw a young man sitting motionless as a stone on a bench by the ticket counter near where I stood, hands between his thighs. The stranger stared straight ahead with a downcast expression, lost in thought, wearing a black pea coat and tweed flat cap too big for his head, loose-fitting grey cotton pants, and a burgundy dress shirt open at the collar. His heavy-soled brown boots were tied with striped workers’ laces, and he clutched the strap of a large canvas bag. No rings, no necklace.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I approached, turned away, looked around, and walked past him again to take a closer look. He had a boyish face, with full lips, prominent ears, narrow-set eyes, and a wide nose, but with a high bridge and thick, slanted eyebrows, almost Slavic, and dark russet hair peeking out from under his cap.

Unable to read the newsstand headlines, I moved to the noticeboard. A dozen ads for hostels and pensions were pinned to the cork and a few were translated into basic English and Dutch, with tiny maps showing their proximity to the station. I stood there, examining a word in one posting for Pension Normandy around the corner, blanking on the meaning of chauffage, cursing my parents for being too cheap to send me to French immersion, when the same stranger appeared beside me, standing very close, perusing the ads. Glancing over, I saw we were the same height, but he had broader shoulders, with pale skin and a line of delicate moles behind his ear, high on his cheeks, and on the crease of his mouth. They gave his face depth, but also innocence, like a baby’s that had never seen the sun. I remained still, remembering chauffage meant heating. He turned to me.

“Are you looking for a room for the night?”

“I sure am.”

“Oh great, we could find one together to save money, if you’re interested.”

We exchanged those familiar glances, more than a few beats longer than usual.

“Saving money is always interesting.”

“Have you seen anything good, close, and cheap?”

He sounded French. The timbre of his voice was softer and deeper than I imagined, which aged him attractively, and I guessed he was several years older, no more than twenty-five. I pointed to the one with chauffage.

“It means heating.”

“It certainly does.”

“We won’t be cold, anyway, and it’s right around the corner.”

We introduced ourselves and shook hands. Louis was assured but shy, perhaps not inclined to engage in spontaneous conversations with strangers. Had I refused, I was sure his response would have been a simple nod and polite bow.

We left the station through the swinging doors into traffic, and Louis pulled the brim of his cap down, covering his face. Shafts of sunlight peeked through heavy clouds. He directed me across the street, past the drop-off lane, clutching my elbow and pointing me away from our intended route to avoid passing five gendarmerie standing by the entrance under the monumental stone and glass facade. Surprised by the security, I asked if he knew what was going on.

“Central Paris has been targeted by a series of political bombings, shocking the city. They were very bold, but I didn’t expect the police.”

Once we had gone twenty metres, he turned us back toward the east pilaster and around the corner, briefly removing his cap to wipe his forehead.

“A Red Army splinter group named Action Directe assassinated a French general in January,” he said, “and a few days ago, a Marks and Spencer department store was blown up very close by. People were killed and wounded, and now there are so many armed officers. Even in Brussels-Midi station, there were a lot of police. I saw you admiring the concourse. Is this your first time seeing Gare du Nord?”

“I love old ironworks. I was thinking of where to spend the night because I have little money and need to make it last.”

“I’m fine with sleeping outside or eating for free, but not on this trip. So it’s good we ran into each other.”

Louis glanced behind us as we walked. His most distinguishing trait was his anonymity. He was hard to spot in a crowd, making me question if it was intentional. In a police lineup, he’d be chosen last.

“And yourself? Where are you going and for how long?”

“It’s complicated,” he said, “but I’m thinking of moving on. I have no agenda and no plans for tomorrow.”

We exchanged looks as we walked, but an awkward silence dropped over us and he changed the subject back to trains.

“I have only been to Paris a handful of times before, but my father spoke of Gare du Nord when I was a child. He arrived here as a refugee from East Germany in the 1950s. In a course on European photography at school, I studied the work of Édouard Baldus, who took large-scale panoramic pictures of the French railways. You would like them if you appreciate the station.”

“What do they look like?”

“Baldus invented the landmark photograph, leaving out people, allowing the images of the architecture alone to speak for who made them.”

“Are you German?”

“No, my father lived in Belorussia, but was Polish, and my mother was Belgian. My parents met after my father was transferred to Belgium, which had more lenient asylum policies for refugees from the East. France had always been sympathetic to communism, which blinded them to what was happening to Poles in the Soviet Union.”

Louis looked over his shoulder again.

“But perhaps now,” he said, “they will reconsider.”

Night Terminus. Copyright Ellis Scott, 2026. Excerpt printed by permission of Dundurn Press.

___________________________________

Ellis Scott has published nine short stories in literary journals, including the Iowa Review, Yolk, High Shelf Press, and the Fiddlehead. His first short story was nominated for a 2020 Pushcart Prize. Night Terminus is his first novel. He lives in Canada.