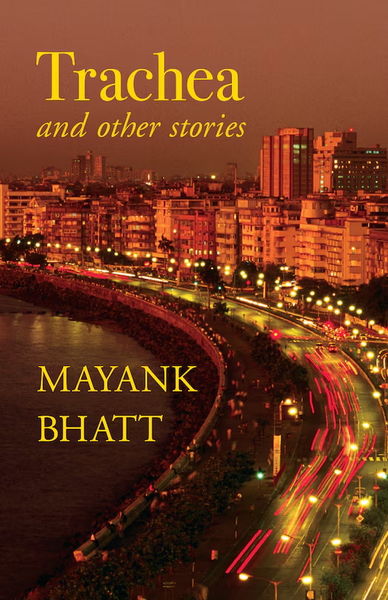

Read an Excerpt from Trachea and Other Stories, a New Work of Linked Fiction from Mayank Bhatt

A long-time fixture on the Toronto literary scene, Mayank Bhatt has built a reputation for his fiction for nearly three decades now, and his latest work of linked stories will only add to his readership.

In the expertly crafted, Trachea and Other Stories (Mawenzi House), the collective tapestry of episodes revolves around Sharad. We follow his journey from childhood in India and the tragic death of his father, to his being raised by his grandmother, becoming a journalist, and marrying and Indo-Canadian woman. This leads him to becoming a Canadian—of sorts.

Through all of these linked pieces, the author paints a rich portrait of one man's complex life. They tell the story of his struggles and triumphs, and all of the experiences that eventually make him an "uncomfortable uncompromising new Canadian."

We've got a selection from this new work to share with our readers today on Open Book, which you can find right here!

An Excerpt from Trachea and Other Stories by Mayank Bhatt

Excerpt from the story "Lemon"

1975

“Is it a kiss if I suck the lemon that you sucked, too?”

Masuma looked at me but didn’t answer, she smiled. She took the lemon back from me and sucked it again. Her lips puckered at the sour taste, and she shut her eyes, savouring the moment. Before giving it back to me, she sprinkled some more salt-pepper-chilli powder on it. I sucked the lemon again, hoping to get a taste of her but it tasted just tangy.

We had walked away from the others in our group, leaving behind the manicured lawns of the park and into the wild growth of shrubbery. The forest and mountain were not too far. The heat from the early afternoon sun was intense; bees and other insects swarmed over our heads. Our palms were moist with sweat, our fingers intertwined into a firm grip, proclaiming our defiance, our daring, as it were, but there was no one around to be shocked at the sight of two teenagers walking in a park, holding hands, sucking a lemon.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

We sat under a tree, still holding hands, and but for the buzzing of the insects and the chirping of the sparrows, it was all quiet.

I just wanted to be with her. There was nothing to say. She was quiet too; and that was odd because usually she just couldn’t stop talking. Her loose glasses often slipped, and she pushed them impatiently up the bridge of her nose.

After a heartbreakingly long silence, which both of us couldn’t bear but didn’t know how to end, she asked: “Do you know the saddest short story in the world?” Without waiting for me to respond, she began narrating it.

“Once upon a time there was a couple, a woman and a man. They had been together for many years. Then one day the woman got sick and bedridden. The man looked after her for some time but then got tired and fell in love with another woman. He started giving his wife poison pills that would kill her gradually. The woman, who still loved her husband, knew that she was a burden on him. She would throw away the pills after the husband left the room. You see, she didn’t want to live anymore, and she thought that if she stopped taking those pills, she would die sooner.”

She paused and looked straight into my eyes.

“Men are such beasts,” she declared, looking at me sternly.

I nodded agreeably, although I wasn’t convinced that men were beasts. I mean, they could be, or they couldn’t be. I wasn’t one, for sure.

“I hope you don’t grow up to be a beast,” she said, looking at me accusingly. She seemed convinced that I would grow up to be one by default.

“Do you want to kiss me?” Masuma asked suddenly. We were still holding hands. She moved closer to me.

“I have never kissed a girl,” I said, and I looked at her uneasily.

“Have you kissed a boy?” she asked and smiled wickedly.

“No…”

“OK, let me teach you how to,” she said. She then took off her glasses, pulled me closer to her and put her lips on mine. She tasted of lemon. Then she pulled away. Her eyes were still shut tight.

“How was it?”

“Great! Open your eyes,” I said. She did and smiled. “Did you like it?” I asked.

“You will get better with experience,” she said.

“You will let me kiss you again?”

“Not today. We must go, or the others will come looking for us,” she said and got up and began to run. I followed her. We were the last pair to reach the class meeting spot. All the girls, including Masuma, giggled. We got on the school bus and returned to school.

I hadn’t learnt anything new about plants and animals. But I had kissed a girl for the first time in my life. I was still in a bit of a daze. It was unbelievable. I had been with the most beautiful girl in our school, I was talking to her, walking with her, holding her hand, sharing a lemon with her, and kissing her, and the best part was that she was leading me all the way.

Mrs Iyengar taught us English. She was as tall as most of the class, which made her shorter than most adults. She wore a starched cotton sari every day and poured a bucket of coconut oil on her hair every morning. She also wore large, thick-framed glasses that she took off when she read. She knew she wasn’t a favourite of her students and worked hard to uphold that reputation.

The first time I met Mrs Iyengar was on my first day at school in grade 10. She told me to sit in the second row in front of her. Masuma was sitting on the bench and moved a little to make place for me.

Mrs Iyengar was to be our class teacher. “If you don’t know yet, let me inform you before we begin our class,” she announced, and the class fell into a hushed silence.

“Our Prime Minister has declared a national Emergency. She has jailed all prominent leaders. Democracy is dead in India,” Mrs Iyengar declared. We looked at her with bemused expressions. Then she placed a big book and a small book on her desk. She lifted the big book with some effort and held it up for all to see. It was a book bound in dark green cloth, with the spine and edges in deep brown leather. “This is the Complete Works of Shakespeare,” she said, and then asked, “Who was Shakespeare?”

A number of hands went up, including Masuma’s. Mrs Iyengar picked Masuma to answer.

“He was a writer. He wrote many plays,” Masuma said in her tinny voice.

“Correct. Very good, Masuma,” Mrs Iyengar said and smiled at her. “Writers who write plays are called playwrights,” the teacher added.

Then she lifted the smaller book and read aloud the title of the book. “Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare.”

“Shakespeare was a playwright. Plays are like the movies but instead of seeing everything on a big screen, there are live actors on a stage,” Mrs Iyengar said. “How many of you have seen a play on a stage?”

Again, many hands went up, including Masuma’s. But this time, Mrs Iyengar didn’t pick her. She looked at me.

“I went to see a play in Gujarati with my Ma and Dadi,” I lied. Had she asked me the name of the play, I would have been caught. I had never seen a play. But I didn’t want everyone to know that we were poor. I looked at Masuma as I sat down. I nodded and smiled weakly.

“I am Sharad.”

“I am Masuma. I am a new student,” she said.

I offered her my hand, but she didn’t want to shake it, so I let it fall limply on my lap.

In the background, Mrs Iyengar was talking about Shakespeare. I wasn’t as interested in what she was saying as much as I was in this new girl sharing my bench. But she was listening with rapt attention to Mrs Iyengar’s stentorian voice as she explained the importance of Shakespeare to the English language.

“After the Bible, Shakespeare has given the English language the most number of words, but if you read his original plays, you will not understand anything, which is why we read Lamb’s version,” Mrs Iyengar said.

___________________________________________

Mayank Bhatt immigrated to Toronto in 2008 from Mumbai (Bombay). Since then he was actively engaged with the Toronto literary scene and was a board member of the Toronto Festival of Literature and the Arts (TFSALA). His debut novel, Belief, was published by Mawenzi House in 2016. His short stories have been published in TOK 5: Writing the New Toronto, Canadian Voices II, the Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and the Beacon.