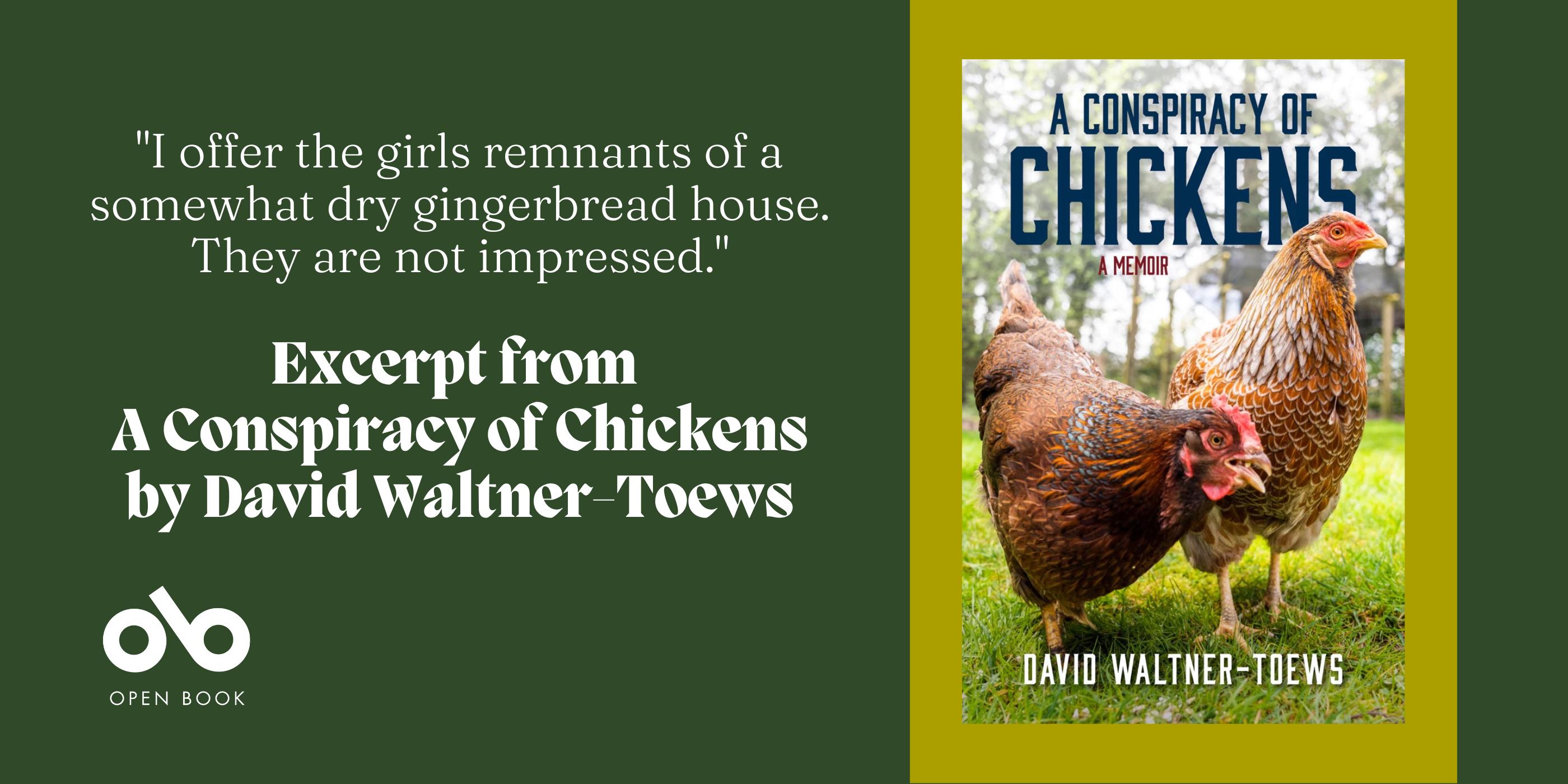

Read an Funny, Gentle Excerpt from Veterinarian David Waltner-Toews's Memoir of Backyard Chickens

When we think about the relationships between humans and animals that have changed the course of history, it's easy to default to the obvious: the horse, the dog, the ox. But there is a more humble animal who has influenced human history in myriad ways that is often forgotten: the chicken. From bird flu to farming, eggs to feathers, chickens have served as food, income, companions, virus vectors, and much more.

No one knows this better than veterinarian and University of Guelph professor David Waltner-Toews, whose work in the epidemiology of animal-borne infectious diseases has taken him around the world. His personal story with chickens however, started not with his research but with a box of chicks gifted to him by his wife: a flock of tiny backyard chickens to call his own.

The experience sparked his memoir, A Conspiracy of Chickens (Wolsak & Wynn), which follows not only the adventures (and misadventures) of the now-popular hobby of raising backyard chickens, but also weaves in Waltner-Toews' expertise about the role the birds have played in our collective history, our relationships with urban animals, and our own place in the natural world. Showcasing the often-cheeky personalities of the birds themselves, Waltner-Toews, who has published numerous books of poetry and fiction in addition to his scholarly work, wins readers with madcap moments and thoughtful reflections.

We're excited to share a passage from A Conspiracy of Chickens today, courtesy of Wolsak & Wynn. In this sweet and funny excerpt, we get a glimpse into life with chickens (one which may feel surprisingly familiar to anyone who has ever taken care of small children). Combining the witty and wild with the natural and contemplative, A Conspiracy of Chickens is a book-form antidote for anyone who is feeling burnt out, overbooked, and separated from their essential, natural self.

Excerpt from A Conspiracy of Chickens by David Waltner-Toews:

On Epiphany Sunday, I make cabbage borscht, as a sort of cleanser after all the Christmas carbs. Then I pull on my patched jeans and rubber boots and head out to clean the coop and change the water. I offer the girls remnants of a somewhat dry gingerbread house. They are not impressed.

Just after chore time, the hens raise a ruckus. This is not, I can tell, mere dissatisfaction with the eating fare. A northern goshawk, about the size of an adult chicken, is perched on the neighbour’s tree. Listen, ask anyone: I love nature. Big, soaring, raptors inspire me. But not in my backyard (unless they are attacking squirrels). My girls squawk and hide under the juniper. I figure they are safe there.

I wave a rake at the goshawk and throw bits of branches and walnuts. The bird moves closer and settles into a tree just above my head. I am freezing. My wife brings out warmer gloves and a winter jacket.

She also hands me the fancy catapult (a.k.a. slingshot) I got for Christmas from my son-in-law. It’s an heirloom from a genuine farmer who apparently used it to scare away predators from her flock.

I shoot walnuts, which flop into the ground or fly wildly astray. Golf balls or rocks seem risky, as the back of our neighbour’s house is entirely made of glass. The hawk watches me, mildly amused. She hops to another branch. She is very quiet. Eventually, Nettie steps out from under the bush. I catch her in my arms and dash her over to the run, where I lock her in. Eventually, the goshawk disappears, and the girls cautiously emerge. My wife catches Elfrieda and carries her to the run. The others are skittish but we lure them to the run with breadcrumbs.

Ruby, seemingly having heard rumours about Hansel and Gretel, the breadcrumbs, and the ensuing menu plans, is at first resistant. We try chasing her, luring her, using breadcrumbs and threats. She stubbornly refuses to head into the run. She circles the coop, snatches breadcrumbs, runs for the prickliest shrubs near the fence. If we open the run door, the others want back out. Finally, we manage to cajole her into the coop, closing the hatch behind her. That leaves only Katie, the lowest on the pecking order.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

My wife retrieves a butterfly net from the attic and I figure out how to assemble it. I suspect that, to the chickens, this looks like a giant bird of prey. Katie, hiding under the juniper, is no doubt calculating the trade-offs between the theoretical threat posed by a hawk and the certainty of bullying in the coop. We play tag around the coop, and then around juniper bush – her screaming and running all around the yard, me tearing after her with the butterfly net. The residents in the high-rises overlooking our yard have seen this particular episode before, and are no doubt breaking out their beer and binoculars as they place their bets.

Finally with a combination of threats and softly-spoken pleasantries, I corral her into the run and close it, then let the others out of the hatch again.

Later, I check out northern goshawks on the Audubon site: “A powerful predator of northern and mountain woods. Goshawks hunt inside the forest or along its edge; they take their prey by putting on short bursts of amazingly fast flight, often twisting among branches and crashing through thickets in the intensity of pursuit.” So much for the safety of the juniper.

The borscht, having simmered an extra hour, is just the right thing.

That night, I find six hens lined up on one of the roosts. Katie is by herself on the other, perhaps for having aroused me to “punish” her flock-mates by making them stay inside after school. Not sure what the epiphany was. That I talk the talk but don’t really love wildlife? That chickens can make me look ridiculous?

The next day is warm – up to 1℃! After the scare with the raptor I wait until mid-afternoon to let them out. Nettie is not impressed and comes poking after me before running across the yard with her wings spread and then back again, meeting a chest-bump challenge with one of the others. This evening, it is dark by 5:30 p.m. and I go to close up the run and the coop. Before I close everything, I turn on the light in the run to check levels in the heated waterer so I won’t have to worry about it in the morning. I am surprised to see Katie sitting outside, atop the waterer, when all the others are inside. She listens as I talk quietly to her for a few minutes, but when I reach to touch her she squawks and runs inside. When I look into the coop, the other six are all on one roost and Katie is at the back, on a separate perch.

One might almost think the chickens were human.

They don’t like the brightly frosted Christmas cookies, shaped like waffles. The cookies were a gift from someone; I didn’t like them either, so I suppose I can’t fault the girls for their food prejudices.

At night there are five on the front roost, two snuggled on the back. Nettie and Katie, the Little Red Hen. Queen Anne and her handmaiden?

***

A year later, when I checked on the hens just before bed, they were all on roosts – except little Katie. She was in the most favoured corner nest box. I go around to the egg door to check under her; she immediately left the box. There were no more eggs. The next day, the arrangement of birds at nightfall was the same: four on one roost, two on another and little Katie in the nest box. And then it occurs to me that by snuggling into that box no one can peck at her during the night, and she wakes up in the morning firmly ensconced in the favourite nest, not having to fight for a good place to lay. She may be small, she may be pecked on, but by gum she's a clever little hen.

__________________________________________

David Waltner-Toews is a veterinary epidemiologist and university professor emeritus at the University of Guelph. He was founding president of Veterinarians without Borders/Vétérinaires sans Frontières – Canada and a founding member of Communities of Practice for Ecosystem Approaches to Health in Canada. In 2010 the International Association for Ecology and Health presented him with the inaugural award for contributions to ecosystem approaches to health, and in 2019 he received an award from the World Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Besides being an author of many scholarly books and articles, he has published six books of poetry, a collection of recipes and dramatic monologues, a collection of short stories, two novels, and various books of popular science including On Pandemics: Deadly Diseases from Bubonic Plague to Coronavirus; The Origin of Feces: What Excrement Tells Us About Evolution, Ecology and a Sustainable Society; Eat the Beetles: An Exploration into our Conflicted Relationship with Insects and Food, Sex and Salmonella: Why Our Food Is Making Us Sick. His nonfiction books have won awards in the US and Canada, and have been published in Japanese, French, Chinese and Arabic.