Robert Colman Explores the Loss of Memory and Self in a Profound, Personal Poetry Collection

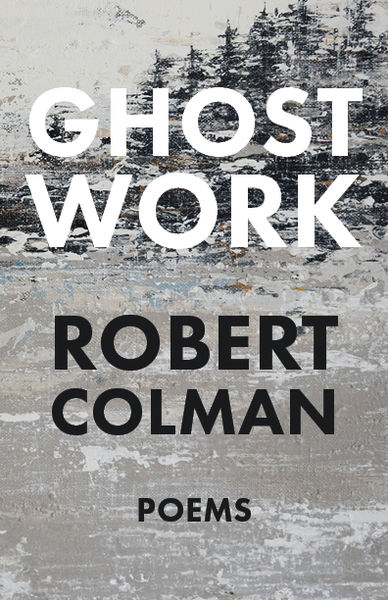

How do we redefine the self when memory begins to deteriorate? This is the central question at the heart of Robert Colman's new poetry collection, Ghost Work (Palimpsest Press).

In this profound and personal suite of poems, Colman delves into the experience of a son gradually losing his father to dementia, using a range of techniques to capture the depth of emotion that someone feels while watching someone they love lose their memory and sense of self.

The collection is both a tribute to a lost family member, and an important meditation on the fragility of human bodies and minds. These poems illustrate the significance of familial connections, and hint at the broader social concerns that orbit those suffering from illness, and those who care for them.

In this Line and Lyric Interview, Colman talks about his new book, and how it took shape.

Open Book:

Tell us about this collection and how it came to be.

Robert Colman:

Ghost Work is a suite of poems that explores the gradual loss of my father from dementia. It came to be because I wanted to better understand that sense of loss, it’s gradual and then seemingly suddenly rapid nature.

OB:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

RC:

I am notoriously bad at choosing titles, so I thank my editor Jim Johnstone for seeing this as the ideal for the collection. “Ghost Work” is the title of a poem in the book, but more broadly I think it resonates because, in the hardest moments of trying to connect with someone who has dementia, it can feel like contacting the ghost of the person you loved.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Was there any research involved in your writing process for these poems?

RC:

I did read about the stages one can expect to experience a family member’s dementia progression, which was helpful both during my father’s illness and after his passing. Since I wrote much of the book after his death, that research reframed our interactions, clarifying what, in the moment, I was too involved with to fully appreciate.

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

RC:

I was surprised by how important a role form played in finding a way to effectively describe this journey. For instance, early in the writing process, the pantoum felt like the shape I was living in. Thanks go to Shane Neilson, who first suggested the form for my experience. Later, when dissociation felt like the only place my father and I lived together, the ghazal seemed like a way forward. My wife and I were travelling in Spain in 2019 and I took John Thompson’s collected poems, knowing that this was likely the only form I’d be able to write in coherently during that time. The six-part “Lost on the Way to Tortosa” was the result.

OB:

Did you write poems individually and begin assembling this collection from stand-alone pieces, or did you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

RC:

I didn’t set out to write a book about dementia, but the strength of the first two pantoums I wrote had me thinking quite soon that it made sense. Loss, which is the heart of this book, is such a broad topic, so although the book is primarily about my father’s illness, broader social concerns are knit into the larger work.

OB:

What's more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

RC:

The opening of a poem draws the reader in, so I’ve always worried about that in framing my work. That said, I will often agonize over the final lines of a poem for many months before I am satisfied with them. You have to have the right opening line to lead you to the ideal conclusion.

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

RC:

I read voraciously during the first year and a half of the pandemic. Along with many newly released Canadian books of the time, such as the work of Roxanna Bennett and Tolu Oloruntoba, I was filling gaps in my knowledge of writers such as Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, and Carl Phillips (in the latter case, both his poems and essays). The work of other poets, such as Richard Siken and Natalie Diaz, arrived at just the right time to help save certain poems in ways that I still struggle to fully explain.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

RC:

I dedicated the book to personal support workers, hospice employees and volunteers because they were instrumental in making my stepmother’s life better during my father’s last years, and eased my father’s final days. Service in the community is so critical and difficult. Doing so in kindness the way these people did is moving.

OB:

Is there’s an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

Although I am the narrator in most of my poems, I tried to capture my father’s perspective in several poems throughout, taking hints from conversations we’d had to place him in his illness at certain times. The book became an attempt at an arc experiencing the progression of dementia. It required my father’s presence to be fully realized.

OB:

What are you working on next?

RC:

I am currently working on a book of essays and criticism that is due to be published in 2026 or 2027. There is also an eco-themed poetry collection that remains in its protean stage of development.

_______________________________________________________________

Robert Colman is a Newmarket, Ont.-based writer and editor. He has been involved in trade publications for the manufacturing industry for more than ten years. Colman is the author of two other full-length collections of poetry, Little Empires (Quattro Books 2012) and The Delicate Line (Exile Editions 2008), and the chapbook Factory (Frog Hollow Press 2015). He received his MFA from UBC in 2016 and served on the editorial board of PRISM International from 2015 to 2019.