"The Pull of Words Had Become Urgent" Read an Excerpt from Music, Late and Soon, Robyn Sarah's Memoir of Her Two Artistic Passions

An out-of-the-blue phone call changed the artistic landscape of Robyn Sarah's life. A decorated poet with 11 collections released over more than four decades, Sarah is an integral part of the poetry landscape in Canada. The elegant simplicity of her work, packed with moments of keen insight, has earned her awards and praise for years. But there was another art form that had fallen by the wayside for Sarah: piano music, a passion from her youth. When she decided one day to call up her childhood piano teacher, she didn't know the impact that phone call would have.

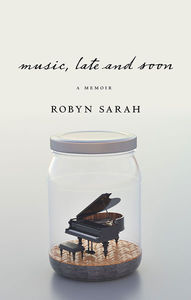

Music, Late and Soon (Biblioasis) is Sarah's memoir of relearning her love of music as an adult after decades away. Once a serious music student specializing in the clarinet and headed for a career of orchestral performance, Sarah changed course to writing but never forgot her first love.

Music, Late and Soon is a meditation on artistic passion through the lens of both writing and music, and on identity and aging. It is, also, crucially, the story of Sarah's relationship with her long-lost music teacher, and the bond between them both in the distant past and the newly rekindled present. We're excited to present an excerpt from this moving, inspiring story, courtesy of Biblioasis.

Here we meet Sarah as she opens up about how writing came to supplant music in her life, how she was drawn slowly back to her musical roots, and a dream that unexpectedly changed things for her.

Excerpt from Music, Late and Soon by Robyn Sarah:

[A Second Chance]

For most of my adult life, I’ve been a word person – a poet, writer, and literary editor; for twenty years a college English teacher. I have always been a word person; I began writing stories and poems almost as soon as I could hold a pencil. But music was central to my formative years, and for nearly a decade I entertained a notion that I could one day support a writing habit by playing clarinet in an orchestra. My mother’s sage advice that I take an academic degree concurrently with my Conservatoire studies, so as to have “something to fall back on,” was to be expected from a parent widowed at twenty-seven with two children. The advice served me well but failed to recognize that when one has something to fall back on, one is likely to fall back on it.

Missing from this picture is the piano. Piano was my first instrument; I’d had private lessons from childhood and kept them up all through high school, even after clarinet supplanted piano as the focus of my time and attention. But I never thought of playing piano professionally. In all those years I never played in a student recital or even took an exam (my teacher didn’t believe in them). By the time I entered university at seventeen, piano lessons had become irregular and soon lapsed, though I returned to them briefly in my early twenties.

I was twenty-four when I finally abandoned thoughts of a musical career and quit studying both instruments. It was becoming apparent I could not juggle a career in music with the needs of literary creation: music would take all. And the pull of words had become urgent. Of course I told myself I would still play, and of course that didn’t work out. Clarinet fell by the wayside quickly: the embouchure has a low tolerance for fickleness, and without the pressure of scheduled rehearsals and performances, there was no motivation to practise daily to stay in shape. The limitations of the instrument didn’t foster much desire to keep it up alone: unlike a keyboard instrument, a clarinet cannot play more than one note at a time – it cannot play chords to accompany a melody, nor a second part to harmonize with one. My Conservatoire friends, bent on careers and beginning to freelance, had no time for recreational music-making. It proved hard to find amateurs advanced enough to play chamber repertoire I would find satisfying, harder still to schedule mutually convenient rehearsal times. I soon gave up trying. Then, for a number of years, I found myself without a piano. By the time my life was rooted enough to own one again, I had two preschoolers and a job as a college English teacher.

My two professional-quality clarinets languished unplayed in their dusty cases. No one knew me as a musician anymore. But I had a piano. So began my thirty-five years as a closet pianist on a part-time, self-coached, on-again, off-again maintenance regime.

*

What brought me to emerge from that closet at an age when any possibility of a musical career was long behind me? What made me decide I needed a teacher again, after half a lifetime’s desultory piano-playing on my own? There was a dream I once had – one that I periodically found myself remembering – that seems, obscurely, to hold an answer.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It was one of those dreams where at first you’re not sure if you’re remembering a dream or something that really happened: I was back in my early twenties, the period when I had last taken piano lessons. It was a warm spring afternoon and I was running uphill from the bus stop towards my piano teacher’s house, late for a lesson I had nearly forgotten about – remembering, with a jolt, when there was just a bare chance of getting there on time if I left immediately. A lesson, moreover, for which I had hardly practised and which I had already postponed once for that reason. In the dream I had recently resumed lessons after a lapse, but despite my best intentions I was not practising regularly, and this was not the first time I would be showing up flagrantly unprepared. On top of it all I was late. How could I excuse myself? Would my teacher decide I was wasting his time? His response to my last return had been distinctly cool, his voice on the phone reserved; I felt he was taking me back on sufferance. His wife answered the door and seemed surprised to see me. She went into the next room to speak to him, then came back and told me I was mistaken – my lesson wasn’t until this time next week. Relief flooded me: I had been granted a second chance. I wasn’t late for my lesson after all; I hadn’t utterly disgraced myself; I had a whole week to prepare now. At which point I woke up.

Only the fact that the house in the dream was no house my piano teacher ever lived in tells me this was a dream. The rest is all too true to life: my ambivalence, my fits and starts, the angst and self-disgust that went with them. I loved the piano. I wanted the lessons badly. But I had too many other irons in the fire to apply myself consistently.

At this distance in time, dream and memory have run together and it seems to me that in real life I did not seize that second chance: I never showed up for the next lesson.What I did around this time, along with my young first husband, was to pack my life into storage and head for the West Coast on a one-way ticket. The piano we had been boarding for a friend passed into another friend’s keeping. We assigned the lease on our flat, distributed furniture here and there on long-term loan, shipped a trunk of books and a manual typewriter to await us in Vancouver, and got on the train with nothing but knapsacks. My plans, which included writing a book, were open-ended. I must have told my teacher I was leaving, though I probably put off telling him for as long as I could. We must have said goodbye. There must have been a last lesson, either before or after I told him. I have no recollection of it.

The persistence of the dream, though – the way it kept coming back to me – tells me I must all along have felt there was some unfinished business in my life attached to the piano. And the tenor of the dream was not unhopeful: it left a door open. It was not an ending, as it threatened to be, but a deferment.

*

A deferment of what, exactly? I had never performed or aspired to perform on piano: there were no failed ambitions to address. Though I was playing repertoire considered advanced when I stopped studying, I never thought of myself as a pianist. When the piano came back into my life – that is, when after five years without an instrument, I suddenly had one under my roof again – it came as a gift from my parents, with my children in mind. It didn’t occur to me to take lessons again myself. I was nearly thirty; who took piano lessons at thirty? It was enough to sit down for a few minutes after supper, while the kids wound down towards bedtime, and see what my fingers might have retained of my repertoire, trying one old favourite or another from memory until I got stuck and had to dig up the score. That I could remember as much as I did was gratifying, but I was lazy about relearning passages I’d forgotten – generally ones I’d been lazy about getting down solidly in the first place. There wasn’t a piece that didn’t have at least one black hole in it – a spot where I was bound to trip up, usually past hope of recovery.

Still, playing was pleasurable. I didn’t get much chance to do it uninterrupted. Weeks might go by when I didn’t play at all because of family or work pressures, or because the piano had gone off pitch and I couldn’t afford another tuning so soon. When I was off teaching in the summers, I played quite a lot, reviving old repertoire in rotation, but for a long time I played only music I had played before. When I did venture to try a new piece, it was always with the feeling that I was getting away with something: maybe I could learn all the notes, even achieve some fluency, but surely I must be missing something essential?

Well, yes. I was missing my teacher. But did I need his permission to learn a new piece? Had I not, over the years of study, internalized enough to carry on by myself – trusting his voice in my head, trusting the acute awareness of touch and its relation to sound he had cultivated in me that activated itself the instant I sat down at the keyboard? So I argued with myself when, from time to time, nostalgia for piano lessons washed over me. Time to grow up, kiddo. It’s not as though you were one of those people who always dreamed of playing an instrument but never had the chance as a kid, or who took lessons for two or three years and then quit, to regret it later. You had close to ten years of lessons with a master teacher. If at your stage you need a teacher to start you on a new piece of music, there will be no end of needing a teacher. Besides – where was my teacher? I couldn’t imagine studying piano with anyone else, but even if I had seriously wanted to return, it didn’t seem an option. The years were taking me farther and farther from a plausible point of re-entry: If at thirty it had already felt too late, what was I to tell myself at thirty-eight? at forty-five?

Still the thought kept returning: If I had not decided at fifteen to make clarinet my primary instrument, what might I have achieved on piano? I couldn’t help wondering how far I might get even now, if I were in a position to throw everything else over and make the piano my primary focus. Could I make up for lost time? Could I cross over into another life – one I had prepared for but abandoned before I began to live it? Ah, but that preparation was on another instrument. And I had struggled with performance issues: bad nerves, memory lapses, a discomfort with the spotlight – almost never did I play my best under pressure. If at twenty-three I could not perform on clarinet to my satisfaction, what hope of emerging as a middle-aged Jill-come-lately on piano?

It wasn’t the performing I missed about the life, but the preparation. It was the singleness of purpose, the clarity of focus, the long hours of absorption in practice. The simplicity of waking up every day knowing exactly what I had to do: having a score in front of me, instead of the blank page or blank screen that faces a writer; having a schedule of practice, lessons, and rehearsals to give structure to my week, instead of random sessions shadowboxing with the Muse. Not least, it was having a teacher – by turns a guide, a coach, a guru – and not being alone with the work, the way a writer is alone with the work. There were times, especially when I felt blocked in my writing, when those early years in music felt like a paradise lost.

*

In the years after my children moved out on their own, I found myself playing a fair amount of piano for somebody who wasn’t a pianist. Progress remained Sisyphean as other commitments took me away from the keyboard for days or weeks at a time, but something was changing. I had begun to make demands on myself. I wanted to be able to get through pieces without stopping. I wanted to clean up the black holes in my repertoire – nail down the notes in passages I’d never properly learned; see if I could figure out what was hanging me up in spots where I chronically derailed. I wanted to work up a few pieces to a level where I could perform them reliably from beginning to end, at least for family or friends. The music itself seemed to be demanding this. The better I played, the more it wanted to be shared.

Gradually, thoughts about “what might have been” shifted to thoughts about what might still be. Thoughts coalesced into an idea: maybe I could devote some time – a year, say – to studying piano intensively, with the goal of playing a small recital on my sixtieth birthday. And then write a book about it. Rumour had it my old teacher was still around: I had heard of sightings at the university where he was professor emeritus, engaged in continuing research. If I approached him with the project, might he be willing to help me prepare? Even just to lend me his ears from time to time? Suddenly this seemed, quite simply, to be what I was supposed to do next. To pick up where I had left off with the piano and take it to its logical conclusion: a performance. To set myself that challenge and give myself that gift – the gift of one year. If the goal was a performance, I could be allowed to have lessons again. If it was in the interests of writing a book, I could justify the expense to myself, the hours spent at the instrument. I would have an excuse. Why I thought I needed one is an interesting question.

What if my teacher wasn’t available, or wasn’t interested? I’d done the math: he must be at least eighty. Even if he was in good health, he could be excused for not wanting to oversee the possibly hare-brained project of a long-lapsed former pupil, herself hurtling towards sixty. But already I was thinking if I had to, I could find another teacher – the idea didn’t depend on him. His web page at the university listed contact information, but the page was ten years old. I procrastinated for a week, then dialed his extension; it accessed an active voicemail box. The recorded greeting was his voice. I listened, froze, and hung up; decided to email instead.

When Phil Cohen phoned a week later, the strangest thing about hearing his voice again was hearing his voice again – live, this time, on the other end of the line. He sounded as he always had – as if I’d been away for a month, rather than thirty-five years. Could it be that all this time he was only a phone call away? Then why did I feel, all those years, as if he existed only in my head – or as if he were on the other side of a wall – in a different dimension, or a different world?

Slowly it dawned on me that I was the wall.

________________________________________________________________________

Excerpted from Music, Late and Soon by Robyn Sarah ©2021 Robyn Sarah. Published by Biblioasis. Reprinted with permission.

Robyn Sarah is the author of eleven collections of poems, two collections of short stories, and a book of essays on poetry. Her tenth poetry collection, My Shoes Are Killing Me, won the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 2015. In 2017 Biblioasis published a forty-year retrospective, Wherever We Mean to Be: Selected Poems, 1975-2015. Sarah’s writing has appeared widely in Canada, the United States, and the U.K. Her poems have been anthologized in Best Canadian Poetry, 15 Canadian Poets x 2 and x 3, The Bedford Anthology of Literature, and The Norton Anthology of Poetry, and a dozen of them were broadcast by Garrison Keillor on The Writer’s Almanac. From 2011 until 2020 she served as poetry editor for Cormorant Books. She has lived for most of her life in Montréal.