"The Terror That is Everywhere" Read an Excerpt from A Knife in the Sky, Marie-Célie Agnant's Story of Haiti’s Brutal Despot

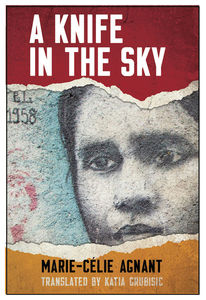

Prize winning Haitian-Québécoise writer Marie-Célie Agnant is celebrated for her rich, complex, moving portraits of women living through colonial power structures. Elegant in its examinations of power and oppression, tyranny and resistance, hew newest novel, A Knife in the Sky (Inanna Publications) is now available in English, translated by Katia Grubisic.

The novel begins with Mika, a journalist uneasily pursuing hidden truths early in the regime of Haiti’s brutal despot, François Duvalier. As her desire to expose the regime's corruption puts her in danger, she crosses paths with a student who will change her fate. The novel then shifts 30 years into the future, following Mika's granddaughter Junon as she witnesses the eventual unravelling of the tyrannical Duvalier dynasty that haunted her grandmother.

A Knife in the Sky is brutal and tense while also thoughtful, sharp, and wise, examining the limits of human courage and perseverance in the face of unimaginable horror, fear, and corruption.

Today we get to share an excerpt from this powerful novel, courtesy of Inanna Publications. Here we meet Mika as she begins to get a glimpse into the rising horrors taking hold in Haiti as Duvalier takes power.

Excerpt from A Knife in the Sky by Marie-Célie Agnant; Translated by Katia Grubisic

Clarisse's Fury

Clarisse and I are driving to the airport. She is smoking one cigarette after another, swearing like a sailor as she swerves to avoid the potholes. Over and over, I recite the same poem again, Rilke. I’m crying; since I found out that Soledad was coming home I’ve done nothing but cry.

There live people, blossoms white and pale,

and die of this hard world, amazed.

And no one sees the gaping grimace

disfiguring, in nameless nights,

the smile of a tender race.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“Do you know, Mika,” Clarisse says to me out of nowhere, “that the monsters who are in power have been intercepting people as they get off the plane? Most of them have never been released.”

I don’t react.

“They have a copy of the manifest, and an army officer checks off the passengers’ names as they get off the plane. Anyone coming from Europe, especially Eastern Europe, is detained. If at least Charles-Émile had deigned to come with you... Because of him, now we’re going to land right in the cesspool of criminals the airport has become. I suppose he had an excellent excuse for not coming to welcome his daughter, as always, didn’t he? If anyone touches a single hair on Soledad’s head, he’ll have to deal with me,” she spits, her voice distorted by fear and fury.

This is what I was dreading, I think while Clarisse gabbles on; she’s going to complain about Charlot the whole way there. I close my eyes, but Clarisse pesters me, her voice like a stubborn insect. My silence offends her, and she doubles down: “Mika, you’ve always been like this! You say one thing and do another. Haven’t you ever stopped to wonder why?”

Clarisse punctuates her scathing proclamations with a godawful kissing of her teeth, which has always driven Bé around the bend (when we were young, Bé told Clarisse it was the height of vulgarity). I don’t know what Clarisse is talking about, and I don’t want to know. I think about seeing Soli, whom I haven’t seen for two years, and I try to stay calm. My sister’s words come back to me now in a fog, where politics, personal relationships, and emotions are all mixed up. I should have gone to the airport alone, or else asked Salnave or maybe Jean-François. I’m kicking myself for not having thought this through. Have I always depended on Clarisse?

The sun is shy today, only a thin glowing film sits over the horizon. But no matter how brightly it shines, it can’t hide the menace that surrounds us, it can’t make us forget the terror that is everywhere, spreading like the destruction all around us: concrete, asphalt, torn-down buildings, mountains of garbage, putrid smells, and stray dogs, mangy and starving, dogs full of ticks scratching themselves furiously in the middle of the road, and the clamour, human anthills, dense smoke, sirens, greyish trees covered in thick yellow dust, and in every corner, scavengers lying in wait.

We watch the people going by: they’re tired of fighting, tired of being constantly harassed by the pack.

“Have they just decided to sink into this misery forever?” Clarisse grumbles, finally changing the subject.

“What else can they do, locked up on this island?”

“Every night boats are leaving, loaded with peasants fleeing atrocities and murders, running away from the gangsters who are trying to confiscate their land. It’s happening now. It’s always happened here. Other beasts replace those that came before, and on and on. And then there’s us, like animals. Hunted.”

“Must we pave the whole ocean with bobbing dinghies full of refugees so that the killing finally stops, and we have peace?”

“We’d only be feeding the sharks. And those who survive the crossing end up rotting in concentration camps in the United States. Imagine the arrogance: even today, those reprobates are still lynching negroes. They’re the same men who landed in this country in 1915 to enslave us and force us to bow down before them—wi bwana, wi misye blan.”

“You’re forgetting that we are the one who are primarily responsible for this situation, we put Duvalier in power.”

“No need to remind me!” she breaks in. “But they’ve been fucking up the whole time! And you’re forgetting that the balance of power is so unequal that we don’t stand a chance.”

She lets loose a peal of laughter, the way she does, which scares the bejesus out of me. And doesn’t let me get a word in edgewise: “We forced those hired guns to go back to their country; do you really think they’ll ever forgive us? Squatting there on all their riches, with nothing to do all day long but shit on the rest of the world—and believe me, they do it gladly. They’re the same as the French, how many times do I have to tell you? Don’t you remember everything they did to us here before they left? Have you forgotten that they killed Péralte, then Batraville, who were fighting against the occupation in this country? Péralte was murdered by the sergeants Henneken and Button, and they were rewarded for the assassination! Péralte’s corpse was gibbeted on a cross—as a symbol, powerful and persistent. And the purpose of the demonstration?”

“To show us that as masters of the world they were going to make us to carry the cross! I know the chorus, darling.”

“Well, you—As a journalist, that’s what you should be writing about.”

Clarisse doesn’t think too highly of me working at the newspaper. I don’t blame her. In the end, it’s her impatience with the state of the country—her legitimate impatience—that makes her so baleful. As usual, I turn a deaf ear.

“It’s true that Péralte was murdered by the Americans,” I say at last. “What’s also true is that they would undoubtedly have killed him one way or another. But he was betrayed by one of his officers, Jean-Baptiste Conzé, who guided the Marines to his hideout. Making us out to be victims doesn’t serve our cause, you know that as well as I do. All it does is reinforce a collective exculpation.”

“We’ve been so busy defending ourselves with whatever scant means we have that we’ve never had time to build a nation for ourselves. How can we survive in a sea full of sharks? We don’t even have a voice! We haven’t had a voice since...”

“Maybe one day we’ll get back the voice that was silenced,” I sigh.

We cross a canal. Muddy water trickles beneath the rickety bridge, and animals and people wade about. On the left, a maze of alleys has taken over a small hill. Other alleyways, dug right into the ground, run almost to the top. There, in the slums, flimsy shacks are perched so high it’s like they’ve been hooked in the sky on an invisible thread.

***

The airport is crowded, hot, and humid. The plane is late. Clarisse can’t stand still. The atmosphere is unbreathable. There is only room for assassins: soldiers, the death squads and their American and French advisors, and other puppets. The parking lot is packed with death cars: Citroën DS, Mercedes 220, Vauxhall, Jeeps. Clarisse stomps around, complaining about the heat. She’s thirsty, she looks like she’s about to cry, and I’m praying, begging all the saints in heaven. I dread Clarisse’s outbursts more than anything else in the world. Not now, I tell myself, I can’t deal with it. The loudspeakers crackle grimly: a plane has landed. Soon Soli will be here.

__________________________________________

Excerpt from A Knife in the Sky by Marie-Célie Agnant, translated by Katia Grubisic. Published by Inanna Publications. Copyright by Marie-Célie Agnant 2022. Reprinted with permission.

Marie-Célie Agnant is an award-winning Haitian-Québécoise poet, storyteller, and novelist. Her most recent works are the novel Femmes au temps des carnassiers and the poetry collection Femmes des terres brûlées, which won the prestigious Prix Alain-Grandbois.

Katia Grubisic is a writer, editor, and translator. Her work has won the Gerald Lampert award fand been shortlisted for the A.M. Klein Prize and the Governor General’s Award for translation. www.katiagrubisic.com