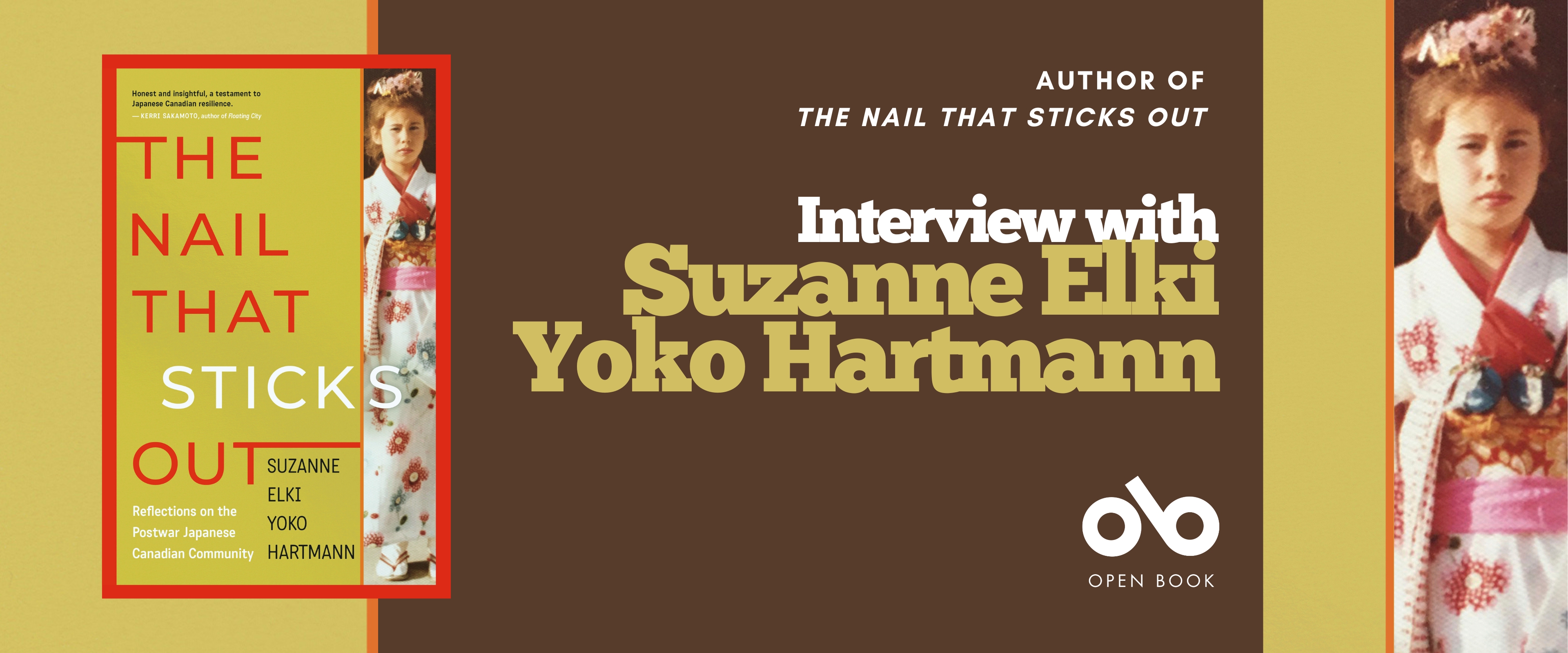

Two Cultures Collide in an Essential Memoir About Japanese-Canadian Cultural Resilience by Suzanne Elki Yoko Hartmann

Though too-often overlooked in discussions about Canada during and after World War II, the experiences of Japanese-Canadians during that time are a window into the fearmongering and xenophobia that must also partially define the nation and the unforgivable actions taken in the shadow of that war.

There have been a number of illuminating books about the topic, and so many descendants of these survivors have told stories about the effect of this era on their forebears, and how it has trickled down to future generations. In a new hybrid memoir, titled The Nail that Sticks Out (Dundurn Press), author Suzanne Elki Yoko Hartmann delves into her own family's history, sharing the accounts of those who took the full brunt of internment camps, forced resettlement, and the erosion of their culture.

The author's mother was just a baby when her family was torn from their home and shifted around from one makeshift prison camp to another, and Hartmann explores the pathways of her family members and the strain that these experiences put on them. But the memoir also celebrates the people, places, and traditions that preserved their culture, and the many lasting and impactful achievements that were made by the very same people as they rebuilt their lives.

Check out this fascinating True Story Nonfiction Interview with the author, and read more about the origins of this important work.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Suzanne Elki Yoko Hartmann:

My only child, Camille, had been bugging me for some time to document our family stories – not only to chronicle the journey of our ancestors but to honour them by providing a record for future generations. Family stories are often complicated and filled with sensitive issues. There were loads reasons to get started and a growing urgency: the Japanese Canadian community was evolving and we had lost so many of our older family members. Both my grandmother and mother survived incarceration during the Second World War, but their memories were starting to slip away.

The more I learned about their history, the more in awe I became of their accomplishments. It’s an inspiring story of resilience and I felt compelled to share their determined efforts and those of a community that persisted despite all odds.

In addition, I urge anyone thinking of writing their own family stories to start today – as time works against us. I wanted my grandmother to attend the book launch this fall but sadly she died earlier this summer. She was instrumental in sharing much of our history and I’ll be forever grateful for the time we had together.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

SEYH:

Despite having worked in both broadcast news and as an editor, copyeditor and researcher at consumer publications for more than 20 years, this work challenged my rigorous standards for authenticating details. To add to this daunting task was the pressure of probing traumatic issues – specifically the wartime narrative of incarceration, dispossession and relocation. Other writers had already explored these issues and at first I didn’t think I needed to tell that story, but when I discovered many people were unaware of Canada’s dark history, it became clear I needed to set the scene for context.

Memory has always been flawed. That much I knew. Perception too, becomes clouded with age. I wanted to separate fact from fiction and tried to consult as many sources as possible. Speaking with family members or reviewing things they wrote revealed different versions of occurrences and it became apparent my research needed to be expanded exponentially as discrepancies emerged. Armed with my own recollections, I set out to verify and expand these narratives.

While I’ve done my best to get the facts straight and consult as many sources as possible, many records remain elusive. It was also shocking to see errors on official documents and inconsistent historical record keeping. Because many archival materials were handwritten, my speculation is there were language barriers or miscommunication at best, and prejudice or dismissive attitudes at worst. This difficulty in acquiring accurate data created another level of dedicated research. And anyone who like me finally stumbles across travel logs or other ancestral evidence knows it feels like winning the lottery. Other inconsistencies I attributed to misprints – we’re human and mistakes do happen. Overall discovering any oversights only served to reinforce my habit of scrutinizing all sources.

OB:

What do you love about writing nonfiction? What are some of the strengths of the genre, in your opinion?

SEYH:

My background in broadcasting and community news exposed me to a more journalistic style of writing, so delving into nonfiction was an easy leap to make. I love learning new things and it’s easy to fall down rabbit holes as you start diving into any research.

One of the strengths of the genre is being able to combine a variety of different writing tools to capture, share and bolster the writing with all the information gleaned from your research. I’ve used braided essays to weave different elements together and appreciate how this method allows the writer to incorporate different threads of information into what I hope makes for a more compelling work for the reader as well.

When I started writing the essays, the work began to evolve during the researching process. As new information presented itself, the story took on a life of its own. This resulted in the writing moving in different directions despite establishing some themes at the onset. For me, this type of flexibility and fluidity is essential – since my thought process is not always organized or linear. Plus, it gives the genre an organic element, which might not be possible in more rigid or formulaic types of writing.

OB:

Do you have an opinion on how the word nonfiction is set – i.e. with or without a hyphen?

SEYH:

This certainly isn’t an open or closed case (sorry, I couldn’t resist). Punctuation has a way of eliciting strong opinions from word nerds, writers and copy editors alike – and since I fall into all those categories, I can honestly say I have considered it on more than one occasion.

Working for consumer magazines and news outlets has firmly entrenched my preference for CP (Canadian Press) Style. With the advent of my book moving through the traditional publishing route, although I had some knowledge of Chicago (Manual of Style), I admit wasn’t prepared to be immersed into a world where the Oxford comma reigns supreme!

To say the least, I spent a lot of time looking things up during the editing stages of my book. CP Style says hyphenate non-fiction both as a noun and for adjectival usage while Chicago says it should be closed. Even the parchment I received from the creative nonfiction program at King’s College University has it closed.

While I don’t think it’s as controversial as some words or inciting as the Oxford comma –there hasn’t been a public outcry since Weird Al released his infamous parody “Word Crimes.” Clarity, consistency and brevity are always key for me, but sometimes it’s out of your hands and you need to respect the style of the publication.

OB:

What does the term creative nonfiction mean to you?

SEYH:

During my time at King’s studying creative nonfiction, they firmly imparted the idea that there is no fiction in nonfiction. And in fact, writing creative nonfiction requires a greater burden of proof. That said, in conversations with other memoir writers, I’ve discovered there are many different standards and approaches.

There will always be those lost or forgotten details and questions you could never ask for whatever reason – and if we sometimes speculate about any situation, we need to be honest with the reader and identify these methods as we round out sections of the work while remaining true to the narrative.

However particularly in historical nonfiction, it’s wonderful to be able to use elements of creative writing to help moments in time jump off the page. Even if you’re a history buff or student, who wants to read a textbook of facts? It might take a bit more work to reconstruct a timeline of events into a gripping scene, to create suspense with a series of telling details you’ve dug up, or heighten the drama or emotional connection with snippets of dialogue from an interview – but isn’t this the craft we strive and aspire to create?

_________________________________________

Suzanne Elki Yoko Hartmann is an editor and the author of a children's book, My Father’s Nose. Her work reflects her roots as a fourth-generation Japanese Canadian with German ancestry, and explores cultural memories, meaningful coincidences, community, and identity. She lives in Toronto.