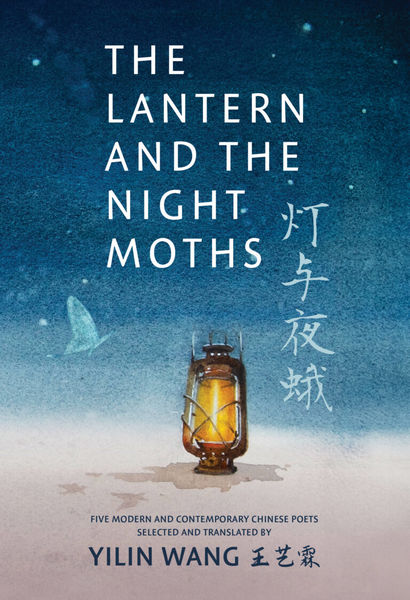

Yilin Wang Curates a Crucial Anthology of Sinophone Poetry with The Lantern and the Night Moths

While the work of Tang Dynasty Classical Chinese poets such as Li Bai, Du Fu, and Wang Wei has long been celebrated in China, and throughout the world, there are key texts that add to this tradition that have been somewhat overlooked in broader translation.

In The Lantern and the Night Moths (Invisible Publishing), Chinese diaspora poet-translator Yilin Wang remedies this by translating selected poems by five of China’s most innovative contemporary poets: Qiu Jin, Fei Ming, Dai Wangshu, Zhang Qiaohui, and Xiao Xi. The collection can be read together as a series of ars poeticas for modern Sinophone poetry, one that redefines the work that came before, and paves a more comprehensive path forward for this unique poetic line.

The collection is augmented by Wang's personal essays on the craft of poetic translation, and modernistic poetic approaches in China that parallel, contrast, and sometimes even dovetail with poetry from the West.

Read this fascinating interview with one-of-a-kind poet and translator Yilin Wang, as part of our Line and Lyric Interview series:

Open Book:

Tell us about this collection and how it came to be.

Yilin Wang:

While there is a long history of Chinese poetry, especially Classical Chinese poetry, being translated into English, many of the first and early translations were completed by white academics rather than translators who have actual lived experience and familiarity with the linguistic and cultural context of the works. Some of these translations are even what’s called “bridge translations”—in other words, writers who did not know the actual source language or nor its context would use literal translations provided by an actual native speaker to create a “translation”—what I think of as their imagination of what the source text to be, rather than a recreation of the source.

Frustrated by this long history of cultural appropriation, and the very small number of Sinophone poetry books that are translated each year, I wanted to create an anthology of Chinese poetry in translation that responds in part to all of this. I ended up curating a collection of poems by five of my favourite modern and contemporary poets. Their voices are all very distinct, but I think of them as each speaking to classical traditions while offering their innovative spin on the voices that came before. Together, their work can be seen as a collective series of ars poeticas on modern Sinophone poetry. For each of the five poets featured, I also included a personal essay on translating that poet’s work. I used this opportunity to reflect on the art and craft of poetry translation from my perspective as a queer femme of the Sino diaspora and to discuss the many ways I have approached translating a text over the years.

OB:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

YW:

The book’s title The Lantern and the Night Moths is a reference to two of the translations featured: “lantern” and “Night Moths.” In the poem “lantern,” Fei Ming wrote, “the lantern light seems to have written a poem; / they feel lonesome since i won’t read them.” For me, these two lines convey so much about the power of ambiguity, silence, and negative space within Sinophone poetry. Even a flicker of light can write poetry, yet who is there to pay attention and read it? Well, lantern light often attracts moths in the dark. Traditionally seen in Chinese culture as the returning spirits of ancestors, moths are guided by light, and even mesmerized by it. Yet it’s also dangerous for the moths even if they get too close to the flames. If they do, they may be engulfed by the fire, and then, they’d be reborn once more. For me, the relationship between the lantern and night moths is an illustration of the relational nature of translation itself and of the many tensions underlying it. To translate a work is to engage in dialogue, between the translator and the author, between the source text and the target language, between a book and its readers.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Was there any research involved in your writing process for these poems?

YW:

So much! The feminist poet Qiu Jin, for example, really loved to use allusions, references, and idioms in her work. Furthermore, her work was mostly published posthumously, which meant that there are different conflicting versions of the same poem. I often had to consult multiple annotated editions of her work while translating. Research can take many hours.

What’s more, given my process is rooted in care, reflection, and close reading, I also try my best to understand the context in which a poem was written. This helps me better put myself in the poet’s shoes. It means biographical and historical research. I went down some deep rabbit holes as I learned about the creative practice of all three modern poets featured in the book. I also had long discussions with the two contemporary writers, who shared multiple interviews they did in Mandarin.

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

YW:

I think I have had one of the wildest debut book journeys ever, stranger than I could have ever imagined. While I was finishing up a draft of my essay on translating the work of the poet Qiu Jin—and as mentioned, I do a lot of research during my translation process—I discovered that the British Museum had been using my translations of Qiu Jin’s poetry in a major exhibit without permission, credit, or pay for over a month. I then had to fight a long, exhausting battle with the museum to get them to fix their terrible mistake; they doubled down in their refusal to credit me properly, going as far as removing my translations and the original poems in Chinese.

All this happened while I was still writing essays and revising translations for the book. It was extremely exhausting. It also really demonstrates how translators can be exploited by large colonial institutions, academia, and publishing. We are so often overlooked and underappreciated. The incident has made Qiu Jin’s poetry so much more important to me as well. Translating her work now has taken on great personal significance, and I ended up revising the initial draft of that essay multiple times to convey all of this.

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

YW:

I re-read Gillian Sze’s Quiet Night Think, one of my favourite collections, which interweaves poems and essays so skillfully. The way Gillian wrote about Li Bai’s poetry and generational poems really invited me to reflect on my own relationship with Sinophone poetry and my mother languages as well as helped me think through how to write about translation in a more personal, intimate way. I also love Don Mee Choi’s translator note in her translation of Phantom Pain Wings by Kim Hyesoon, where she reflected so thoughtfully and creatively about her translation choices and her conversations with the author. And when I was going through the emotional stress of fighting the British Museum, I also found strength and inspiration from two stunning chapbooks put out by Ugly Duckling Presse—Sawako Nakayasu’s Say Translation is Art and Mirene Arsanios’s Notes on Mother Tongues.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

YW:

My wàigōng (maternal grandpa) passed away while I was in the midst of working on this book. I meant to visit him in 2020, but I was not able to make it back to China because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then my trip kept getting delayed. I lived with my wàigōng for a few years when I was growing up, and he’d always share Chinese folktales and poetry with me, which made me fall in love with Chinese literature. Several months before he passed away, I made a promise to bring him a copy of the book. I wanted to share the book with him so badly—just to hand a copy to him, so he could look at it, and tell him, look, I have translated a book of Chinese poetry. The book is dedicated to him and my wàipó. My work as a translator wouldn’t be possible without all that they taught me, and I try to honor their memory with my work.

OB:

For you, is form freedom or constraint in poetry?

YW:

Oh, it can be so hard to translate form. While the formal elements of a poem can work perfectly in the original, this often doesn’t work when directly carried into another language, since every language has its own formal conventions. I often have to get very creative. I have learned to try to convey the spirit of the poet’s formal decisions and focus on the poem’s emotional impact, such as its shifts and turns, rather than to be tied down by every aspect of form. While this can be really challenging, I also think translating form really forces me to learn new tools, to experiment, to think outside of the box. It pushes me to explore the limits of language and see what’s possible.

_____________________________________________________

Yilin Wang 王艺霖 (she/they) is a writer, a poet, and Chinese-English translator. Her writing has appeared in Clarkesworld, Fantasy Magazine, The Malahat Review, Grain, CV2, The Ex-Puritan, The Toronto Star, The Tyee, Words Without Borders, and elsewhere. She is the editor and translator of The Lantern and Night Moths (Invisible Publishing, 2024). Her translations have also appeared in POETRY, Guernica, Room, Asymptote, Samovar, The Common, LA Review of Books’ “China Channel,” and the anthology The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories (TorDotCom 2022). She has won the Foster Poetry Prize, received an Honorable Mention in the poetry category of Canada’s National Magazine Award, been longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize, and been a finalist for an Aurora Award. Yilin has an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC and is a graduate of the 2021 Clarion West Writers Workshop. Find out more at www.yilinwang.com.