Love Letter to a Stranger in Saint Petersburg

I’ve been thinking since my last post about how to write a communal poetics while in isolation, while I can’t reach out and physically connect with the poetry community that’s been so dear to me for a long time. And that thinking about the common, the communal, is an ache that’s been exacerbated by my most dear poetic comrade, Kate Siklosi, and her writing about witness and connection in her poetics piece up on rob mclennan’s periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. There, Kate writes:

I’m writing to connect. I’m writing to dream. I’m making lists. Past archives and future inventories. Seeing the today and imagining the tomorrow. Building. Travelling across borders. Listening carefully and feeding back. Inviting you in.

And, I’m a woman who loves to make an inventory, who thrives on lists and messy, impermanent archives. So, I thought, why should this digital residency be anything else but a list, an inventory of the poets, writers, thinkers, scholars, and artists who have affected my writing most? I want to count you all, to connect from desk to desk across these mostly-empty streets, and across borders, across oceans, across worlds. That is, after all, what I argued last time that visual poetry can do best. So, from here on out, every post of this residency will be a love letter to someone who has made me rethink my writing, my pedagogy, and my thinking. And today that starts with a weird one, with a poet I’ve never met face-to-face; it feels appropriate in these days of digitized intimacy to present to you an intimacy that has always (so far) been digital. This is a love letter to the Russian poet and scholar Pavel Zarutskiy who is navigating this messy world from Saint-Petersburg, and who has become, in a short time, quite important to me.

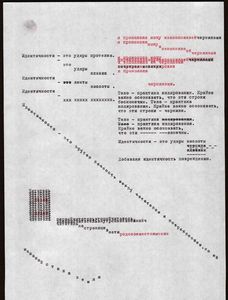

Pavel first wrote to me, I find as I dig through my inbox, almost a year ago exactly: 16 April 2019. He was working on a type-in event as a part of the exhibit that would eventually become Словомеханизмы (Wordmechanisms). He reached out asking if he could translate some of my work into Russian and included as an attachment a photograph of one of my poems, an early draft of the piece “Coding Practice” that would appear in OO, typed on a Russian typewriter. I’m including it here so you can see how much Pavel both stayed true to and evolved the original poem (you can find an early draft of it here).

And here's how the significantly-shortened poem appears, in all its magenta glory, in OO:

In his email, Pavel told me:

I'm not sure in some places whether I got [the translation] correct and in some other cases the poem has slightly evolved, some meanings have lost and some emerged.

To me, at first, it felt strange to translate such a visual medium into a different language, but watching “Coding Practice” evolve as it transformed into Russian characters demonstrated to me that while I am working in a largely visual medium, I’m still doing some of the work of making sense, of giving information. I was reminded of this Wittgenstein quotation from Zettel:

Do not forget that a poem, although it is composed in the language of information, is not used in the language-game of giving information.

But, despite my best attempts at it, I was still—couldn’t help it—giving information. And someone, a complete stranger in Saint-Petersburg, had taken that information and transformed it. Pavel and I have been in pretty steady communication ever since. He translated more of my poems (“Errata” and “I Want a Confessional” which would also appear in OO, and “Eschaton,” which is slated to appear in a pamphlet from derek beaulieu’s no press, then “Mean” and “Rebelling”). He sent revision after revision of “Coding Practice, eventually reproducing my fingerprint with his own. It felt for a moment like we touched, fingertips all E.T.-outstretched across an ocean. But I, with my shitty Americanized monolingualism (save for some conversational Italian that has never served me very well) could not reciprocate. I found ways to pay him back where I could. He asked where he could buy a copy of my scholarly book, Anarchists in the Academy (U of Alberta P, 2018), and I sent him one for free. Then I sent him more pamphlets as they came. Eventually, so enamored with Pavel’s version of “Errata,” I sent him my original typewritten copy because it felt, suddenly, strangely, like it wasn’t my poem anymore.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

My favourite moment of our little digital friendship was when Pavel was translating my poem “Rebelling” (which originally appeared here in The Maynard in 2017), and I made a small request, which now reads almost ridiculous but felt right at the time. I wrote him this:

The poem was written about a friend with cancer. That friend has since passed away. So, if your translation could be in the past tense that would be heartbreaking and beautiful and a lovely homage to my friend. Just an idea.

I’m including his translation here, one of many drafts he sent me as he worked through the poem, giving it much more attention than I ever did.

“Rebelling” was written as a rush of pain watching my friend, the beautiful and deeply missed Priscila Uppal, die of cancer two years ago. I published it quickly with the delightful people at The Maynard and then I thought I wouldn’t look at it again. I removed it from consideration for the manuscript I sent to Invisible Publishing, replacing it with the more jovial “Leveling,” a poem about playing Stardew Valley. But Pavel’s translation work made me keep looking at it, made me revisit the pain, the stuttering ache that I could see very much still in the poem. “I've taken it quite personal,” Pavel told me in an email as he sent another draft of his translation. He told me he lost someone important to him to cancer, too, and that is part of why he was taking so many liberties with the visual poem as he translated. He wrote: “I don't know whether it's good or bad in this case that my personality/memory are also present.” It was a good thing, I think. At least, it felt like it, to have my grief look at his, to have his look back.

And after our grief and our fingerprints and our poems touched, we just kept in contact, like teenaged pen pals from a bygone pre-digital era. We felt suddenly quite close. I watched the exhibit take shape, I looked at his photographs, I watched as journals published his translations with a lot of really lovely joy. He ordered and read OO and sent me his thoughts and a poem responding to the book. We chatted about what COVID-19 looks like in Saint-Petersburg, and what it looks like in Toronto. And I feel like I know him, even if that’s lame. I feel like he’s my friend. I think he might be, this stranger, and I owe him quite a bit for making me realize that even if usually—yeah, most of the time—it feels like I’m just fucking up my nail polish typing fifty consummate “v”s on some silly, archaic machine, someone might read those letters, and they might reach out.

And the job of a poem, the job of a poet, is to reach back.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.