Poetry School: Getting specific with Amiri Baraka

By Deanna Young

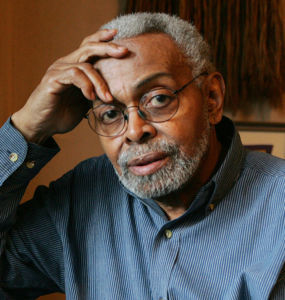

Writing is reading, teaching is learning. As I said in my invitation for readers to join me this month-long online Poetry School, I expected to benefit the most from these researches into the craft and theory of poetry. In fishing around for essays that spark my interest, I have made some marvelous discoveries. This essay on expressive language by American Beat poet and founder of the Black Arts Movement Amiri Baraka is one.

In his essay “Expressive Language” (1963), Baraka posits and promotes a black aesthetic, arguing that “[a]ll culture is necessarily profound. The very fact of its longevity, of its being what it is, culture, the epic memory of practical tradition, means that it is profound.”

Having grown up in the homogeneity of 1970s and ‘80s southwestern Ontario, I recall distinctly believing that I came from a cultureless place—as if that were even possible. Maybe all kids think this, no matter where they are. As children we might not be able to see or imagine the world beyond our street, or the grocery store at the busy intersection. But then we grow, and maybe we get some perspective (perspective is everything, I’m fond of saying), and maybe we see and appreciate where we are from and feel somewhat less like nothing. For feeling like nothing never did anybody any good, nor anybody around them.

Baraka: “And specificity, as a right and passion of human life, breeds what it breeds as a result of context.”

“Specificity” grabs my attention here. “Be specific” we hear in the creative writing workshop, and it is often the right advice.

Sometimes I swear. Okay, a little bit every day. Sometimes more. I know people who rarely swear. These are our dialects. This swearing or not swearing is planted deep in the soil that grew us, no point trying to weed it out now. In my writing it’s got to come out, but swearing in poems is often too much, unadvisable. So if not in vocabulary, then behind the words, as energy. Some of the pauses in my poems might be read as curses.

“All culture is necessarily profound” then, and specific. Baraka uses money as an example. Money does not mean the same thing to him, he guesses, as it must mean to a rich man.

I’m thinking of a time my sister (we grew up together within a specific economic culture) was chatting with a more distant relative (from a difference economic culture) and referred to “a lot of money”. A few sentences later, that money turned out to be far less that the distant relative had imagined. The moment when the discrepancy between intended meaning and assumption became apparent was awkward, all of us standing there in the glaring light of specificity and context. This conversation did, in fact, take place outside, beside a flat ocean, on a cloudless August day.

Business class, agricultural class, working class, welfare class. What does “a lot of money” mean to you?

Baraka: “The social hegemony, one’s position in society, enforces more specifically one’s terms (even the vulgar have ‘pull’).”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

What language do I speak? What language do my poems speak? Is there a discrepancy between the two? If yes, then who—what—am I mimicking? Why? Replace “I” with “you” and take the quiz yourself.

Baraka: “The culture of the powerful is very infectious for the sophisticated, and strongly addictive. To be any kind of ‘success’ one must be fluent in this culture. Know the words of the users, the semantic rituals of power. This is a way into wherever it is you are not now, but wish, very desperately, to get into.”

I’ve noticed that when I enter a specific culture, even within my own culture, I very quickly make adjustments to my speech. My vocabulary becomes more sophisticated or less, even my mannerisms change. I go into camo mode, chameleon mode, trying to fit in, I guess. It feels false as first, but quickly becomes the new normal. I don’t make an effort to adapt this way, I just lean that way. I’m one of those people who might move to England and develop a British accent within weeks. I know someone who moved from England to Canada as a child and still sounds British. We are all weird and specific.

Baraka: “Words’ meanings, but also the rhythm and syntax that frame and propel their concatenation, seek their culture as the final reference for what they are describing of the world. An A flat played twice on the same saxophone by two different men does not have to sound the same. If these men have different ideas of what they want this note to do, the note will not sound the same.”

I like the style of this essay. There are gaps to leap over—for me, at least. I don’t grasp all of it. I feel its influence, though. Its specific kind of power.

“Culture is the form,” Baraka writes, “the overall structure of organized thought (as well as emotion and spiritual pretension). There are many cultures. Many ways of organizing thought, or having thought organized. That is, the form of thought’s passage through the world will take on as many diverse shapes as there are diverse groups of travelers.”

Maybe that’s why I don’t make all the leaps. A black man in Harlem in the 1960s is worlds away from me, a white woman in Ottawa in 2019. Still I read, still I want to understand.

Baraka: “[B]lues singers from the Midwest sing through their noses. … And singing through the nose does propose that the definition of singing be altered . . . even if ever so slightly.”

Poetry can speak these forms, I think. The poet’s task is to be specific, to be authentic. If you sing through your nose then write singing through your nose. I’m just guessing here, reaching. I’m learning from Baraka’s leaps. Can’t help it.

“The dullest men are always satisfied that a dictionary lists everything in the world. They don’t care that you may find out something extra, which one day might even be valuable to them. Of course, by that time it might even be in the dictionary, or at least they’d hope so, if you asked them directly”

I love how each year new words are added to the OED. In September 2018, there were 1,400 words, senses and phrases added (I know!), including nothingburger (n.) and arseways (adv.).

Where I come from, 10-month-old babies make strange. My sweethearted grandmother would threaten to wring your neck (as she would literally do to a chicken), right after she hung out the warsh. Gall darn it.

Baraka: “I heard an old Negro street singer last week, Reverend Pearly Brown, singing, ‘God don’t never change!’ This is a precise thing he is singing. He does not mean ‘God does not ever change!’ He means ‘God don’t never change!’”

Two very different statements, yes.

“Communication is only important because it is the broadest root of education. And all cultures communicate exactly what they have, a powerful motley of experience.”

Poets, please. Speak your powerful motley of experience. Be specific.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Deanna Young’s previous books include House Dreams, nominated for the Trillium Book Award for Poetry, the Ottawa Book Award, the Archibald Lampman Award and the ReLit Award, and Drunkard’s Path. Young grew up in southwestern Ontario during the 1970s and ’80s. Reunion, her fourth collection, belongs to that place and time. She now lives in Ottawa, where she works as an editor and teaches poetry privately.