Workspace

By Erin Frances Fisher

1. Desk: the desk belongs to my partner, Bradford Werner. He covered it in plastic during his university years. I poke fun of him for it, but the wood is pristine. I cleaned for this photo, but if you surprise me at home you can tell the state of my project by the state of the desk. Scraps of paper, paperweights, books, notecards—I delude myself in thinking that if I leave whatever-it-is visible, I’ll remember it.

2. Desk chair: my parents bought me the chair after I developed neck and shoulder issues from spending all day at one keyboard or the other. Thanks, parents!

3. Frogs: at some point I owned mitts that looked like frog puppets. I would set them on the counter at my piano studio, and my students, assuming I like frogs more than anything else, started giving me amphibian related gifts.

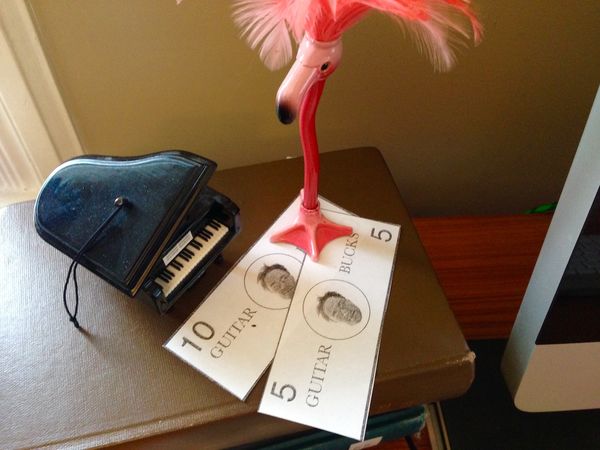

4. Pianos: along the same line as the frogs. On the other side of the room I have a full-size keyboard. The “Guitar Bucks” are my partner’s student rewards (he teaches classical guitar) and yes that’s his head in the centre.

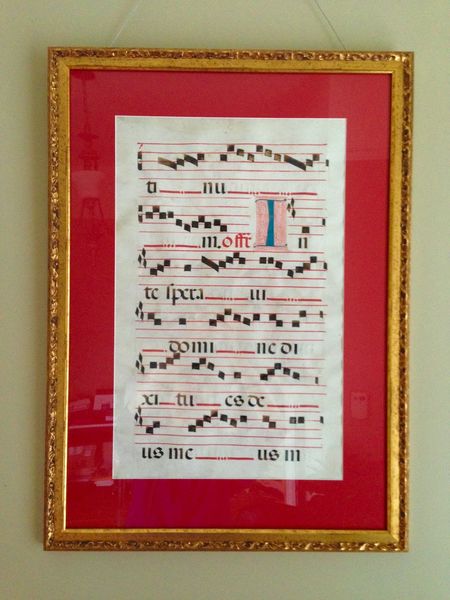

5. Manuscript: A decorative liturgy manuscript leaf on vellum, written in a Spanish scriptorium around 1480. I won it at a raffle held by Early Music Society of the Islands. The EMSI hosts my favourite concerts, and I spend a lot of between-writing time staring at this leaf thinking about who illuminated it around 450 years ago.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

6. Plants: what can I say, they were smaller to start with.

7. Headphones: noise-cancelling. The best gift I’ve been given, and essential for apartment writing. I rarely listen to music while writing, but I do listen to rain or snow storms. Though while I was working on Argentavis Magnificens (a story from That Tiny Life) I listened to Mamoru Fujieda’s Patterns of Plants almost nonstop. It’s a wonderfully strange composition style. From Pinna records:

“Patterns of Plants, composed between 1996 and 2011, is Mamoru Fujieda’s magnum opus. Working with the “Plantron,” a device created by botanist and artist Yūji Dōgane, the composer measured electrical fluctuations on the surface of the leaves of plants, and converted the data thus obtained into sound using the Max programming system. Through a process he has likened to searching “in a deep forest” for “beautiful flowers and rare butterflies,” he listened for musical patterns, and used them as the basis for composing short pieces, which he then grouped into collections reminiscent of Baroque dance suites.”

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Erin Frances Fisher (MFA UVic, AVCM pedagogy/performance) is a writer and musician in Victoria, BC. Her short story collection THAT TINY LIFE was published by House of Anansi Press, March 2018, was a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize at the 2019 BC Book Prizes, and runner-up for the 2018 Danuta Gleed Literary Award. Her stories have appeared in Granta, The Malahat Review, PRISM international, Riddle Fence, and Little Fiction. She is the 2014 RBC Writer’s Trust Bronwen Wallace Emerging Writers recipient. Erin teaches piano at the Victoria Conservatory of Music, and is a sometimes sessional writing instructor at the University of Victoria.

Website: www.erinfrancesfisher.ca