Words & Curds: Ed Piskor & Tom Scioli, Pittsburgh Cartoonists Extraordinaire

By Evan Munday

On May 6, Toronto's streets were already alive with cartoonists and comic book artists. The Toronto Comic Arts Festival was just days away and a number of acclaimed comic-makers were roaming the city's laneways. So I invited two of Pittsburgh's finest cartoonists, Ed Piskor and Tom Scioli, out for a poutine. Piskor is the creator of, most recently, Hip Hop Family Tree. Scioli is creator or such projects at Godland and American Barbarian who is now working on G.I. Joe vs. Transformers. We met at The Beguiling and walked over to the Annex location of Smoke's Poutinerie. Ed Piskor had the 'Hogtown' (topped with mushrooms, sautéed onions, bacon, and pork sausage). Tom Scioli had the 'Veggie' (using vegetable gravy), and I had the 'Veggie Deluxe' (topped with mushrooms, sautéed onions and peas). We talked about comics (naturally), the pop culture mecca of Pittsburgh, graffiti influences, and pierogies. The interview wound up being a nerd's paradise. (You've been warned.) In an unexpected turn of events, all three of us finished our poutines.

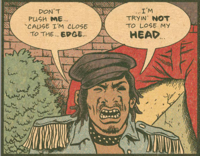

About Ed Piskor: (adapted from the TCAF site) Ed Piskor began his career working with underground comix legend Harvey Pekar, first on American Splendor strips. The duo went on to create two graphic novels, Macedonia (Villard, 2007) and The Beats (Hill & Wang, 2009). 2012 saw the publication of his first solo book, Wizzywig (Top Shelf, 2012) and he's currently working on the Hip Hop Family Tree series published on Boingboing and collected by Fantagraphics. You can visit him online at edpiskor.com.

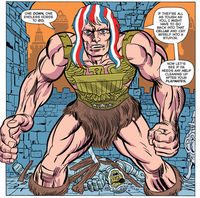

About Tom Scioli: (adapted from the TCAF site) Tom Scioli is the creator of the webcomics American Barbarian, Final Frontier, Satan's Soldier, and Mystery Object. He was nominated for an Eisner for his creator-owned series, Godland, and is the creator of the Xeric-winning The Myth of 8-Opus. He is also the artist and co-writer of Transformers vs. G.I. Joe for IDW. You can visit him online at tomscioli.com.

ED: I've never eaten this kind of thing, so I don't assume that my heart will seize.

EVAN: Tom, your work is obviously influenced by the king, Jack Kirby. And Ed, your latest book is about the history of hip hop. Obviously, these are great interests or maybe obsessions for the both of you. What was your first encounter with either the work of Jack Kirby or hip-hop culture?

TOM: By the late '70s and early '80s, which is when I was a kid and first encountered Kirby – by that point, he wasn't making comics anymore. He was working in animation. He'd sort of gone as far as someone can go – as far as a genius can go in comics at the time. The pay scale was only so much, the freedom that they granted you was only so much. At that particular moment in time.

EVAN: Even the production of the actual comic books.

TOM: Exactly, there was a set format that you couldn't get out of. And ironically, just a couple years later, all that changed. So, he made the move to animation. It was the first time he had health insurance, it was the first time he had a retirement plan. He went from having a piecework job to actually having a real career. A real job that rewarded him commensurate with what he contributed. The stuff that he was doing then was actually my first exposure to his work. And he was doing character designs and story concept designs for Thundarr the Barbarian [Scioli is, coincidentally, wearing a Thundarr the Barbarian shirt], which was a cartoon of the time. And he was also doing stuff for other cartoons, like Super-Friends, that are burned in my memory. But in none of those cases did I know there was a guy named Jack Kirby. I just knew that this show Thundarr had this really creative look.

EVAN: And Thundarr looks the most like Kirby's work.

TOM: Yeah.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

ED: Did you watch Turbo Teen?

TOM: Yeah, I watched Turbo Teen [a show about a teenager who can turn into a car]. I haven't really revisited Turbo Teen since I became someone aware of Kirby and a fan of his work. It would be interesting to see if any of those things pop up. Any of those stylistic hallmarks. Even something like Thundarr, which is the closest anyone up to that point got to having the Kirby aesthetic in a show – other than those old Grantray-Lawrence ones, where you're basically looking at photostats of actual Marvel comics. Other than those, that was the closest they got to Kirby. But that was still a long way from what you would call 'Kirby.'

ED: When you discovered Kirby, were you living in Pittsburgh at the time?

TOM: When I sort of fell in love? Yeah. I mean, by that point, I knew about Kirby, I knew who he was. Around high school is when I went, 'Jack Kirby is the guy who drew a couple of comics that I did that were some of my very favourite comics.' But I wasn't 100 percent on board as a fan. I still viewed those comics as 'Stan Lee' comics. I thought all the things I liked about them were coming from Stan Lee. And then, at some point in high school, when I lived in Philadelphia, I sort of learned about Kirby. But I also had that kind of thing that I find really obnoxious now when I see it in other people, when I was like, 'Oh, Kirby. It's kind of cheesy. He's got these kind of goofy people he draws. They've got goofy teeth.' In Pittsburgh, I was walking distance from awesome comic book shops. So, I'd go in and they'd have, like, the Kirby section. And that was where I really made the connection. 'Wait, this is the guy who did Thundarr – everything I love!' All these sort of scattered things that I loved, and didn't realize were connected, all came from this guy.

ED: We both live in the same town right now, in Pittsburgh. And I was born there. But just to answer your question about the hip hop thing, I was born in '82. So, hip hop was already a nation-wide fad. I was born into it. And the neighbourhood I was from – predominantly black neighbourhood – that was the music of the town that I lived in. And in its truest forms. You'd go to the basketball courts and guys who were waiting to play – to get a chance on the hoops next – they would just hang out on the side and rap to each other. You'd see people in the playgrounds near my house spinning on their heads and things like that. But the reason I was asking these pointed questions to Tom was because I feel like there's some connective tissue between both of our work and a few of the other really awesome cartoonists in Pittsburgh. And I can't help but think it's an environmental thing, because Pittsburgh's the town of Warhol. And pop art. In school, growing up, they'd kind of beat us over the head in a move of civic pride. Warhol created this pop art thing, so you would see Lichtenstein and you would see big paintings with the Ben-Day dot patterns that you would see in comics and, so, that's an aesthetic that I've grown to love. Because you would see those big Lichtenstein things in a small format. In actual comics. And that's a colour palette that I choose for my work right now. And there's another cartoonist, Jim Rugg, who spearheaded that idea. Tom's work is steeped in pop culture. Pittsburgh is just a great pop culture town.

EVAN: There's a scene in Hip Hop Family Tree where they're in the museum looking at the Lichtenstein and thinking, this is no different from the graffiti and street art that I've seen.

ED: Right, right. Those early graffiti artists, they were very influenced by the art they saw around them. And it was almost a postmodern kind of pop-art thing, where they're repurposing characters. Instead of copying from old Russ Heath or Jack Kirby comics, like Lichtenstein did, the graffiti artists of the '70s were using imagery from Vaughn Bode. And I have a whole theory about Kirby being a big influence on the '70s graffiti artists as well.

TOM: Yeah.

ED: Because Kirby was doing Captain America and Falcon, and he was doing Black Panther. And those comics were easily accessible on newsstands, so if these graffiti artists are painting Vaughn Bode comics? To get those comics you had to go to head shop. You know what I mean?

EVAN: You can't just pick them up at the convenience store.

ED: Yeah. So I'm reasonably sure that they were also down with some Kirby stuff. And if you look at some of the lettering on some of those '70s Kirby books –

EVAN: I was going to say, just the sound effects!

ED: Yeah. The Mike Royer title lettering and … shit like that. It's wild. And I don't have a smoking gun where I can point to train where it's Mike Royer lettering –

TOM: At least not yet.

ED: At least not yet, man. But I have the privileged position to speak with old graffiti writers from those days, and they're like, 'Yeah. Kirby, Moebius.' And over the years, they've grown to like – like, Jim Lee is a big influence artistically on a lot of those guys.

EVAN: Tom, you look to Kirby for influence, and Ed, your own illustration seems to be influenced by underground comix from the '60s and '70s. In both cases, you're influenced by artists who had their heydays before you were even born. What do you think it is about these art styles that were popular before you were born that are so important to your work?

TOM: Recently, it's dawned on me a possible answer to that, and I don't know how I feel about this. But I have a tendency to get really bored with things very fast. Familiarity breeds contempt. That seems really strong with me. If there's a song I hear on the radio a couple times too many, I just hate it. But even a song that I really like – I need to space it out. If I play it too many times, I'll start to hate it. It's like a ticking time bomb. As soon as I'm exposed to something, the time's ticking down to where I hate it. It would have been impossible for me to fall in love with anything that was ubiquitous and contemporary. It had to be something that I wasn't getting saturated with or overexposed to. It had to be something that I just sort of found at the back of some weird box. I'd like to think this isn't the case, but maybe if I grew up in the time of Kirby, in the '60s, maybe I'd feel like it was being forced down my throat. Art Spiegelman sort of expresses something similar to that. That he just can't like Kirby.

EVAN: Because when he was growing up, he was just seeing comics by Kirby? Several titles every month.

TOM: Yeah, to him, that was just what superhero comics were. And overly aggressive. But I'd like to think that Kirby's so great and my appreciation for Kirby is so pure that had I grown up in that era, I still would have liked him. But I don't know. I'm grappling with that.

ED: You know what I think? I think that's well-put. You think about other cartoonists that are coming into the vogue now, from the past? You have guys like Herb Trimpe that people are looking at. He would do several monthly books at a time in the '70s, so he was overexposed to a certain extent. And now people our age are going back and digging out his work. We'll know that your theory is law when people are on Sal Buscema's jock.

EVAN: (Laughs.)

ED: I think just inherently with cartoonists, there's some aggressive crate-digging, looking-for-inspiration-and-discovering-new-things component to our brains. My interest in the underground comix: as a boy, I was always interested in subversive things. Naughty stuff. Raised Catholic.

EVAN: You were looking for stuff that was … sinful.

ED: Yeah. (Laughs.) Sure. For sure. I fully admit my interest in underground started just as a quest for pornography in the day before the internet existed. But then, you wise up and realize that Robert Crumb can friggin' draw better than 90 percent of these mainstream guys and has more to say and just a more interesting point of view. But as a boy, it's not like I just discovered that first. I grew up in the '90s.

EVAN: You were a big fan of Image Comics, I've read.

ED: Yeah. For sure. And you would read interviews with Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld, and something they would always talk about is their influences. And the way my brain operates, I'm not so much into the derivative. Give me the original! So then I would read Watchmen and I would read Dark Knight, became a Frank Miller fan and an Alan Moore fan. Start reading interviews with those guys, and start backwards engineering their styles to the point where I was seeing all these similarities. A lot of the same names are coming up in the same breath as Winsor McCay, Chester Gould, etc., you would hear 'Robert Crumb.'

EVAN: Tom, in addition to the Kirby influence, another thing about your artwork style is that the drawings are almost impossible. Every page, every panel has stuff happening in it that couldn't happen in any other medium. It very much takes full advantage of the comic form. It's not drawn television or something like that. It's not storyboards. What draws you to this experimentation of the page or panel?

TOM: I think I just sort of know comics inside and out, just from that natural thing. I love comics so much and voraciously read comics and study them, take them apart. And I've been working for, at this point, a really long time. I just have that toolbox, that bag of tricks that I've developed one at a time. Whatever medium you work in, whether it's film or whatever, you know it inside and out and know every possible mark. Every possible effect. You're going to get to a point where you're going to be employing those and employing them pretty deftly.

ED: In the hip hop world, we call that 'sampling.'

TOM: (Laughs.) Right. I'm so drawn to fantasy and science-fiction kind of stuff. If you want to make a movie or write a book, there are all these things you have to do to make this thing real to me. But all I have to do is draw a picture of something, put a word above it, and it sort of side-steps whatever sort of block that your brain has. You draw some crazy picture and put above it, 'The Strongest Man in the Universe.' Something hyperbolic like that. And then, you're looking at the strongest man in the universe.

EVAN: Obviously. We were talking a bit about production before, and the production of your [Piskor's] book looks so beautiful. It looks like a comic from the '70s or early '80s. With the newsprint. And even the free book for Free Comic Book Day, you can see marker bleed through some of the pages. That was amazing. It reminded me a lot of Afrodisiac, and I know that Jim Rugg helped a bit with the design.

ED: On the free comic. Yeah. The regular Hip Hop Family Tree books are based on – I wonder if these books made it to Canada – the Marvel Treasury editions. The main inspiration for Hip Hop Family Tree is actually Superman vs. Muhammad Ali. Because growing up, the only comic that my friends parents' had in their house was Superman vs. Muhammad Ali. And when you take a look through the book, you see that Muhammad Ali beats the crap out of Superman. So I saw it as a bolstering kind of thing. I wanted to capture kind of that spirit, because I can imagine that my comic will be the only comic in some people's houses. It's really found an audience with people who are down with rap music and hip hop culture, so, I thought it would be awesome if my book is right next to Superman vs. Muhammad Ali in someone's bookshelf.

TOM: Wow.

EVAN: These are the two comics we have.

ED: So, I stressed the production, because I really wanted to capture that vibe. And it also is indicative of the time that the story takes place. Those treasury editions came out in the late '70s – the more popular ones. So I'm going to retain that format throughout. But there are other little things here and there. Like, the free comic was inspired by '80s Marvel Comics.

EVAN: Yeah. The cover had that – was it '85 when they did the portrait covers? [It was actually 1986.]

ED: Yeah, the 25th anniversary Marvel issues with the portraits. And I've been in comics for ten years. And that free comic is the first comic book that I ever made. Meaning standard format that you can bag and board. So, I'm super stoked on it. And we're putting together a slipcase set of 1 and 2 for the holidays, and packaged with it is going to be a 5 1/2" by 8 1/2" ashcan about Rob Liefeld meeting and doing the Spike Lee Levi's jeans commercial, meeting Eazy-E. The comic is going to be indicative of the '90s. So it's card stock cover, foil-stamped, embossed, on glossy paper.

EVAN: That's the perfect format for that story. You both live in the Pittsburgh area. Is there an equivalent food delicacy to poutine local to Pittsburgh?

TOM: I can think of a very direct one. The Primanti Sandwich, which has pieces of bread, and then some coleslaw, and French fries … and then you put the meat or whatever over it. So, that's a direct one. But that's specific to one restaurant. I guess a more universal thing would be the pierogi. [Gesturing to Piskor.] You might have more insight into this, because you were born and bred in the city.

ED: Yeah, he hit the nail. You consciously brought us to a poutine place, but when people come to Pittsburgh, they hear about the Primanti Bros. Sandwich, but I say, 'No. Let's not go there. That's tourist nonsense.' So, is poutine tourist nonsense or do you guys love it?

EVAN: Well, the thing is, it's only recently come to Toronto. It's more of a Quebec thing. It started in Quebec. And it slowly kind of filtered throughout the rest of – it's become popular in Toronto over the last five (?) years. But for this series, I thought it would be a good gimmick to hook the interview on. People are visiting from another country, from not-Canada – because there are a lot of great Canadian authors and comic artists, but I wanted to talk to people who were visiting from either the States or ideally elsewhere. I talked to an author from Denmark and from Angola recently. And just be like, 'This is what Canadian food is.' There's not a lot of food that's particularly Canadian.

ED: Yeah.

EVAN: A lot of it is French Canadian. Like, there's this.

TOM: And Canadian bacon.

EVAN: Yeah. Nanaimo bars are a dessert.

TOM: I'll have to try those.

EVAN: They're like these little squares of chocolate and, I don't know, a custardy thing …

TOM: That sounds good.

EVAN: Yeah, they're really good.

ED: Do you guys call Canadian bacon 'Canadian bacon'?

EVAN: No, we call it either 'peameal bacon' or 'back bacon.'

ED: Ah. Yeah, oh yeah.

EVAN: Tom, your latest project is G.I. Joe vs. Transformers. Reading it, it really harkened back to the digests I used to read – like, Archie digest-size books – that collected the early issues of the G.I. Joe comic. But I read somewhere that you didn't read those books growing up. You only went back and read them recently. What was that like, reading them for the first time now?

TOM: It blew my mind! I was just reading last night. At The Beguiling, I picked up a stack of G.I. Joe comics and Transformers comics. Old stuff. Because I'm still filling in my collection and bits and pieces are missing. And when I read them, it's like I'm taken back in time. And it's the perfect kind of trip in time, because I'm reading something new, but I'm a kid again. The letter columns and the layouts just take me back. I'm glad that I didn't read them as a kid, because I wouldn't have appreciated them. It would have just been another thing from childhood that I enjoyed. In preparation for this comic, it was a body of work that I got to read and fall in love with for the first time. And I'm wondering, 'Ah, man, what's going to happen with Ripcord? And Zartan?' And since I grew up in that era, kids our age ate it up. It was made for them. Here's this thing that I was programmed to enjoy, and now, after a long, long delay, I'm finally getting it. It's like this catharsis.

EVAN: In both your free comics, you have little bonus stuff that you'd find in old DC and Marvel comics.

ED: I can't wait to put paper dolls in the next comic. If I can find a couple spare pages. Dress up Melle Mel. Don't steal this, anybody reading this. But I'll draw, like, Melle Mel in a cheetah bikini. Like a speedo. And then, have all the outfits around him.

EVAN: That's amazing. How did you research the book? There's a lot of stuff in there – some of the anecdotes are so specific. I love the scene with Disco Wiz and Casanova Fly, who inadvertently cause this blackout, which ends up getting a lot of other early rap artists their gear. How did you find out about these things?

ED: I just gleaned every source that I could find: documentaries, books, interviews – online and in magazines. So, I just have a Vatican-like archive of research material that I can pull from. And the internet is good for more than just pornography, too, so there's plenty of stuff online. Specifically, that one that you mentioned with Disco Wiz and Casanova Fly, if you type their names into YouTube, you will see an interview where they speak about that exact moment. And you hear, in their own voices. It evokes an image in my brain. That's a story that I heard where I was just like, 'This should – it's so visual – it should be put down in comic form.' What I sort of consider myself is more a curator of information, where, as a fan, I know a lot from just being a fan for my entire life. But I'm not just creating these strips from that place. My inherent knowledge creates some destinations where I need to go. So I just zero in and research all of those specific moments and scenarios. And then, inevitably, in these interviews, other things would be mentioned that seemed significant – that might have influenced a song or something – so then you just fall down that rabbit hole. And it's an intense pleasure. It's almost like I'm not a cartoonist. I'm just a curator sharing these discoveries. A lot of people, they automatically assume that if you read a book by somebody, then that author's an expert of the subject matter. And I do know plenty, but what I'm doing with this comic book is sharing my discoveries. Like, archaeological excavation. And I'm sharing discoveries instead of standing on top of a mountain telling you all this great stuff that I know.

EVAN: I wanted to ask you, Tom, how does working with licenced characters (G.I. Joe, Transformers) differ from other stuff that you've done, like Godland or American Barbarian, that's creator-owned?

TOM: When I worked on this, creatively, I just need to pretend, for my own purposes, that it's not a licenced thing. Pretend this is something that I created and allow myself that freedom and range. Just chew things up, spit 'em out. Rip the head off one guy and stick it on somebody else. Really give myself the freedom, because, to me, that's the only way I could make it a good comic. If I approached it any other way, I couldn't see how to do it. The creative approach this is is sort of different from what I've done before, but only because I have this renewed focus on how to make comics. Separate from it being a licence. But in every other way, I'm treating it like anything else.

EVAN: You can kind of tell, because you play with Snake-Eyes's origin. It's not the canon version. Ed, your previous book, Wizzywig. You took things from actual hackers and phreaks, but it was largely fictionalized. But it seems like you have an interest in people who take stuff that exists out there in the culture, and then use it in ways in which it's not intended. Like in Hip Hop Family Tree, there's a real interest in how the actual music was made. Like, we took these particular records that people were listening to for this reason, and then did this. People were using stuff in other ways.

ED: Yeah. I definitely do equate hip hop culture with hacking. Because the true spirit of hacking is exactly as you describe. It's creating new uses that were unintended with already existing things. And you're the first person – that's a connection I've made the entire time, but you're the first interviewer who brought that up, so I appreciate that. I also think that the history of high technology and hip-hop music – these are American creations that most people just take for granted in the States. It's sort of always been there. So I have an interest in that. The comics medium is like my cipher to share information. I'm not saying I'm never going to do it, but to just make up stories and stuff like that? It's fine, but it's not my main interest. I consider myself, because I am compulsive when I get interested in something, I learn about it to death. So then, what happens is I become the cartoonist that is going to be able to make a comic about this or that. I saw that Hacktivist comic. It's wack. (Laughs.) It's just silly. The promise that we've always heard about Japanese comics is that there's work out there that exists for every facet of the culture. Comics about fishermen, comics about tennis … so why not have a hacker comic book? Why not have a respectful comic about hip hop? Not a comic that's, like, just trying to exploit the culture. Not a vanity project for Method Man where he's running around killing zombies. Method Man, the fact that you came out of Staten Island and had a bunch of coincidences and happy accidents and networked to get to a point where you can feed for family for generations? That's more interesting than you going into a dungeon with your modest ninja ability and killing dragons and shit like that. You know? Other interests I have – and they're all connected – things like pro wrestling, skateboard culture. I call them trash pop culture, but it's not trash pop culture to me. It's trash pop culture to, like, your parents.

EVAN: They also seem – correct me if I'm wrong about professional wrestling – but they're all American inventions or creations. Right? And in the free comic book, you talk about the parallels between comics and hip-hop and how they're both American inventions, and you talk about the connections between them.

ED: Yeah. It runs deep.

EVAN: Tom, have you heard anything from Larry Hama or any of the artists who worked on the original G.I. Joe comic books? Or Ed, if you had heard from any of the people featured in the book. I know there are a couple blurbs from people like Fab Five Freddy. But have you heard from any other people in the book?

TOM: Jack Kirby wasn't alive when I started my work, so I never heard anything from him, but I've heard from his children, but specifically for this G.I. Joe comic, I'm anxious and I'm curious to hear if Larry Hama or I guess Simon Furman read it. Larry Hama is so closely associated with G.I. Joe. he worked on it for such a long time and defined it in so many ways. So I would love to hear what he thinks about it. And then, Simon Furman – I don't think he's exactly the Larry Hama of Transformers, but he still made a very large body of work – very personal …

ED: He's the name, when you say 'Transformers comics,' he's the name that comes up.

TOM: He is the name that comes up, but just by an accident of history. He created really great, really personal work over a long period of time, just coming into this thing that was largely created before he got there. He was early, but he wasn't – Larry Hama was there from Day One. He was like Day Three for Transformers. So I would love to hear what they have to say. My personality, I wouldn't want to force the issue, I wouldn't want to say, 'C'mon, guys! Read the issue! What'd ya' think? What'd ya' think?' But if they happen to discover it in their daily life and read it, I'd love to hear what they think.

EVAN: But you're not going to send them a PDF.

TOM: I might do that, too, anyway ... And a gift-wrapped copy.

ED: The way that I started out publishing the hip-hop strips is that I put a new strip online every Tuesday, on a site called BoingBoing. And BoingBoing gets over 4 million unique users a month. And my strip gets between 40 to 50,000 unique users reading the new one. And then, hundreds and sometimes thousands of people each week who read 'em all. By virtue of that, the six degrees of separation game is a non-issue. So what I'm saying is, plenty of people have gotten in touch. And it's been basically unanimous praise a lot of the time. Hip-hop is about – it forces consumerism these days. Where even when I was a kid, if you listened to a record and they would call out the year, you couldn't even listen to that record six months later. Because kids were like, 'You listen to some old crap!' So it's all about buying new things and new cars, clothes, and new records. So, the history is largely forgotten about by the people who are of the culture. And they might have stuff that resonated with them when they were younger, but they're just about the biggest, newest, latest. So, these men and women are very appreciative that someone is taking the time to go back and sort of give them their props. And show how Grandmaster Caz influenced LL Cool J and etc, etc. And, by virtue of these people appreciating the work and digging it, they've also been sharing the links, which created a situation where the book came out in December. It's May, and we have to go into a third printing already.

EVAN: Yeah. They can't keep it in stock at The Beguiling.

ED: They can't. The first printing came out through the direct market on a Wednesday. And on the Friday, we got a call that we needed to reprint it. And then when the second printing finally came out, it was a week that went by, and then they got the call that they needed to reprint. So, yeah. It's very cool.

EVAN: That's it, but I wanted to congratulate you for being the first people I've interviewed out of – I think it's the fifth interview that I've done like this – you're the only two that have finished their poutines.

TOM: Oh, wow. We're hungry. We're hungry boys.

ED: And you interview people from the States?! Man, we ate big portions!

TOM: We're skinny guys! At least, you are.

ED: You ain't lying.

TOM: This is just breakfast.

ED: Yeah, I think they're wusses, man. I'm going to go through the website and take names.

Poutine Count:

Evan: 5

Authors: 2

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book: Toronto.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Evan Munday is the author and illustrator of the acclaimed book series for young readers, The Dead Kid Detective Agency. Both The Dead Kid Detective Agencyand its sequel, Dial M for Morna, were nominated for the Silver Birch Fiction Award.

Evan has worked in book marketing and publicity for ten years, eight of which were as publicist at Coach House Books, and he has since worked as a freelance illustrator and ebook designer.

Find out more about Evan on his website, idontlikemundays.com or follow him on Twitter at @idontlikemunday.