The Stories I Shelve, Part I

By Mark David Smith

With the advent of the Kindle, the refrain among publishing analysts was that the book’s days were numbered; the e-book would change accessibility for stories as the printing press had all those centuries ago. Growth in the e-book market was swift, and publishers scrambled to ensure they could offer their stories on these new platforms without suffering the kinds of intellectual theft the music industry had experienced when it went digital. Fortunately, though, the growth plateaued, and book sales have continued to be robust. Some categories have outpaced others, but when has that not been the case? The jury has come in. People don't just want stories; they want books.

I sometimes recall with a twinge of pity my indifference toward books in university. These were the first books I actually purchased with my own money, not the assigned readers I’d been lent in high school. Granted, I might not have sought out these books on my own had they not been required for my courses, but having been required, those books became part of my developing psyche.

And then I sold them.

Granted, I was the living stereotype of a university undergrad; perpetually strapped for cash, renting a shared apartment, living on a steady diet of Kraft Dinner and leftovers filched from my parents. (I thought myself a culinary creative, adding to my mac ‘n’ cheese such exotic delicacies as tuna, a can of soup, or frozen peas. Genius. Of course, I still ate it straight from the pot with the large mixing spoon.) The money from those books offset the cost of the next semester’s books, and so on. The only ones I kept were the ones the bookstore wouldn’t buy back.

I didn’t realize then what I have come to know: that books are more than just the words on the page or the art on the cover, more than the sums of their parts. Books are themselves things of significance—beyond their words are the memories we attach to those bound pages, the events, the places, and the people they signify.

What follows over the next two blog posts is a list of ten books on my bookshelf that have come to mean far more to me than the stories within them. Here are the first four:

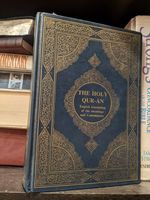

1. English Translation of The Qu’ran

On our way to Uganda from Greece in early 1997, the airline changed our flight, resulting in a 24-hour layover in the tiny Gulf nation of Bahrain. Backpacking at the time, we took advantage of the opportunity to see what we could of this wealthy Arab isle. One of the recommended sites in our Lonely Planet guide was the Blue Mosque, notable for its exquisite tile work. When the taxi dropped us off, the mosque was empty. We took off our shoes and washed our feet, as required, before entering. The poor fellow watching over the place—was he a caretaker?—dropped his jaw in astonishment. He spoke no English, but was terribly excited and motioned for us to stay. Then he got on the phone. Twenty minutes later the Imam of the mosque showed up in his black Mercedes and invited us to sit with him. (a Mercedes in Bahrain is about as common as Toyota Corolla would be here, so don’t get too excited.) What followed was an hour-long discussion of our differing ideas about faith and theology, with an eager group of young Muslim men craning their necks back and forth, from the Imam to us and back again each time one of us shared a point, like they were watching a tennis match. Not that it was competitive; rather we spoke in an attitude of genuine interest and friendship. At the end of our impromptu meeting, we were given a number of Muslim apologetical tracts, as well as a very fine, leather-bound volume of the English Translation of the Qu’ran. It travelled with me to Africa and has stayed on my shelf since we returned home. It reminds me of those people, that place, that time.

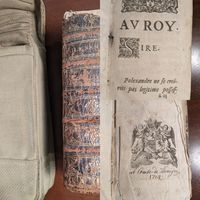

2. Le Premier Partie de Polexandre (edition unknown)

When my stepfather’s father returned from World War II, he brought with him a spoil: a leather-bound copy of Le Premier Partie de Polexandre, a French adventure story originally published in 1619 and extended through various editions and sequels. It has since been passed to me. This edition edition was once in the collection of the Count of Thorigny (“Le Comte de Thorigny”) and has a date of 1714 inscribed in fine calligraphy. I still keep it in the Canadian army-issue green canvas pouch that Grandpa Doug used to bring it back. Of course, that’s his story, not mine. Still, this is the oldest manufactured thing in my possession, and when I hold it I wonder about all the hands that held it before me, the other people over the centuries for whom it was important for other reasons than mine.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

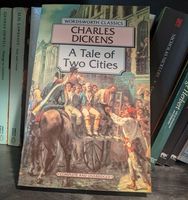

3. A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens (Wordsworth Classics, 1993)

For a time I became enamoured of books by Dickens. I had gone to visit my cousins in Calgary—I had hopes of making the University of Calgary men’s basketball team—and ended up staying for the summer and getting a job. It was my first time really living away from home, and though I was with family I had a lot of freedom to come and go as I pleased. I had lots of time to read, and for whatever reason picked up A Tale of Two Cities. It was one one of those “Classics” tables in the bookstore that offers novels like this for half price. I might have paid three dollars. It was the best of books. It spawned a brief obsession with all things Dickens. That summer I also read Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, and The Old Curiosity Shop. When I see this book on my shelf now, I picture myself stretched out on the living room carpet, my cousins’ dog, Rusty, mimicking my posture, reading for deliciously long stretches. Those were Halcyon days.

4. Art: A New History, Paul Johnson (HarperCollins, 2003)

Beginning around 2006, a few of us at my church decided to produce an arts journal, a magazine devoted to visual art and writing from within the Christian community of Metro Vancouver. We were ambitious, but broke. Still, we managed to produce seven full-colour issues over about 3 years. I was the editor, and as I was fielding visual art submissions as well as written ones, it was suggested to me I might benefit from an education in art history. Art: A New History, is a 1000-page tome following the progression of art from 40,000-year-old cave painting to modern fashion art. It retailed for $60, but was half-price at the Regent College bookstore at UBC. I bought it new for $5 from a used bookstore in Arizona (see references to frugality above). I read the entire book with great interest, but one section in particular. Nestled at the end of the Renaissance section were five pages devoted to a painter I had never before heard of: Caravaggio. People in art know Caravaggio, of course, but the average person really only knows a handful of artists by name, and most of those they only know because of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. But this artist, Caravaggio, fascinated me. He painted photo-realistic images with breathtaking pathos; yet he was also an expert swordfighter and spent the last five years of his young life (he died at 39) on the run for killing a man in a street brawl. My fascination led to the writing and eventual publication of my first novel: Caravaggio: Signed in Blood (Tradewind Books, 2014). That novel got my foot in the door as a trade-published writer, and established my desire to write for children. If it had not been for Paul Johnson’s book, though, who knows where my writing might have gone?

IN MY NEXT POST, I will present six more books on my shelf, books whose value to me lies in the people they remind me of, and the memories we share together.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Mark David Smith is the author of The Deepest Dig and Caravaggio: Signed in Blood. A public school teacher, he lives in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia.