The Stories I Shelve, Part II

By Mark David Smith

In Part I of this blog post, I looked at the importance of physical books in my life, how the books represent more than just the stories within them, that they also hold the stories of their acquisition, the stories of their influence on my life.

In Part II, below, I share six more books (continuing with the previous post’s numbering) whose values go beyond the texts themselves, books whose physical presence is a tangible reminder of people for whom I share a strong bond.

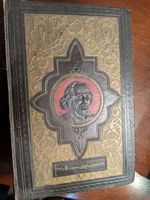

5. The Complete Works Of Shakespeare (Walter J. Black, Inc., 1937)

With its embossed cover and decorative end papers, this is certainly one of the fanciest books I own. I brought it to an antiquarian bookseller when I was in my twenties and paid him $40 to rebind it as the cloth of the spine had begun to disintegrate. He informed me that the book wasn’t worth $40—apparently this was a very popular edition and therefore quite common among used books. But to me it was priceless. It had belonged to my grandmother, who had recently passed away. I have read many of Shakespeare’s plays, of course. When I read them, I think only of Shakespeare’s characters and themes. When I read the same play in this book, however, I feel a connection to my grandmother, knowing that she turned those same pages, gasped at the beauty of those same words. Across time, with that book, we read together.

6. The Deptford Trilogy, Robertson Davies (Penguin, 1990)

My mother was an avid reader, but reading was always a private affair for her. She seldom discussed her books with me growing up. However, at some point while I was in university she passed on her paperback copy of The Deptford Trilogy—Fifth Business, The Manticore, and World of Wonders. I have since read all of Davies’s books, and am thankful that she introduced me to a writer whose characters are more finely drawn than those of any other writer I know. But more importantly, giving me that book was like a welcome into the adult world; she had invited me, somehow thought me ready for that intellectual pursuit hitherto privately hers.

7. The Riverside Chaucer, Larry D. Benson, ed. (Houghton Mifflin, 1987)

One of my favourite classes in university was a course in medieval literature. My professor, Dr. Sheila Roberts, was animated and provocative, and fostered in me and my group of friends a fondness for the culture and poetry of that era. Once, she even made us mulled wine. I made good friendships in that class, some I still maintain to this day. The woman who became my wife was one of those friends. I ended up taking three classes with Sheila Roberts, one devoted solely to Chaucer and which my wife—then my girlfriend—had already taken. I borrowed her copy of The Riverside Chaucer. It is full of her notes (see references to my poverty and frugality, above) and reminds me of those times after class eating lunch, laughing through the “quaint” stories together, ignorant then of the beautiful life I would one day build with a very special woman.

8. The Hobbit (Limited Edition Collector’s Box), J.R.R. Tolkien (HarperCollins, 2000)

I actually have two copies of The Hobbit. This title was one of several books I had to read for a course on teaching children’s literature, and from there I moved into Lord of the Rings. I had purchased a four-book set at the time, but later, while grocery shopping, came across a discount book bin with a surprise: A special publication of The Hobbit in a large box which, in addition to a hardcover copy of the novel, contained a colour map of Bilbo’s journey drawn by John Howe, postcards, and an audio CD of Tolkien himself reading “Chapter V: Riddles in the Dark”. I believe the sticker price was $49. I bought it for $12. I love a good deal. More importantly, I bought a second one for my good friend Dave, who is a far greater Tolkien fan than I am. When I read The Hobbit, I never read from this edition. But knowing it has a twin at my friend’s house makes it symbolic of that friendship.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

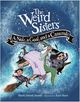

9. A Series of Unfortunate Events, Lemony Snicket (HarperCollins, 1999-2006)

I began reading the first book about the Baudelaire Orphans, A Bad Beginning, to my daughter when she was about seven years old. Because the series had already been out for several years, we had no trouble finding copies of each of its thirteen books. I would read aloud to my daughter each night, and sometimes she would read to me, taking on voices and accents for the characters. (Captain Widdershins was definitely Scottish; Mr. Poe I read with a nasal British accent, a sort of “Pip-pip! Jolly-ho!” creation; and for Count Olaf I tried to do my best Christopher Lee impression.) Now my daughter is twenty, and navigating the new adult world of university and work. Those books sit on my shelf as a reminder of that magical time we had together when she was young, a special time only the two of us shared.

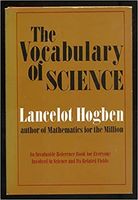

10. The Vocabulary of Science, Lancelot Hogben (Stein and Day, 1970)

When I took on a Master’s Degree in Education, I managed to convince the faculty to let me study Latin and Greek as part of my elective course requirements. Hearing about this deviation from the normal run of courses students in this program took, one of my professors gave me a copy of The Vocabulary of Science, a reference book on the Latin and Greek origins of scientific and medical words. (And incidentally, isn't Lawrence Hogben just the best name for a character? Must use that some day.) My professor's name was Geoff Madoc-Jones, and he had come across the book at a used bookstore and thought of me. He also admitted to being somewhat embarrassed to be singling out one of his students for a special gift—not really appropriate, he said, but too late. I think something of my study of those ancient languages reminded him of the traditional education he had grown up with. He was a proud Welshman, and would occasionally rail out in a violent passion some poetry in his Welsh dialect. He was also the president of the Dylan Thomas society, a group devoted to the memory and reputation of the poet Dylan Thomas. He signed his emails “Geoff Geoff,” which was odd and therefore in character. He cared little for decorum, though he was kind and deeply thoughtful. It was he who showed me how the word principal had gone from an adjective to a noun; that “principal” had originally been short for “principal teacher”—the head teacher—and that in dropping the word “teacher” that job of educating had also been dropped in favour of a far-less-noble managerial role. He was a man who knew himself and acted according to the dictates of his heart and his conscience. He once told us of the story of his failed invasion of the United States, when he and group of other Canadians stormed the Peace Arch border crossing in protest, overwhelming the border guards. In the end, the group lost their momentum, and ended up just sharing drinks at a local pub with those same border guards. He was admirable and entertaining. When I published my first novel, I sought him out because I wanted to share that small victory with him. Sadly, he had died of cancer in those intervening years. I hold onto that book now as I hold onto the memory of a man who inspired me and impacted the way I saw myself and my role as a teacher.

IF I EVER had to replace these books, I would still feel a loss—the replacement copy would not hold the memory of the original. A book tells two stories. One story is on the pages themselves, and is offered equally to everyone. The other is a story only the owner can tell.

Now, you visit your own books. What memories and people are represented by the stories you shelve?

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Mark David Smith is the author of The Deepest Dig and Caravaggio: Signed in Blood. A public school teacher, he lives in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia.