How I look at a map (part two): found poetry

By Matthew James Weigel

In previous posts you’ve seen some of the things I’m thinking through when I’m creating visual poetry. And in the last post we got started working on a new piece by looking through archival material. This will be the second of three parts detailing that process. For convenience, you can find the first part of this series here.

First, we started with source material. I knew that I wanted to work with a map, so I began by checking out the map collection in the City of Edmonton Archives. I’m fascinated with the relationship that mapping holds with the land. A map is not the land, it is a model, a representation, almost a cartoon-world version of how the land really is. In some ways, cities themselves are almost cartoon-world versions of how the land really is. But as an urban Indigenous person, I spend most of my time in the city. The city is the land I live on, the land that nurtures me, the land that makes me, me. Makes me in all the multi-faceted ways in which a home can. So, it’s no surprise that what I write about most is the city.

The map that sparked my creative interest this time was titled “Named and Unnamed Parks”. Knowing that this piece will be about parks, it was time to turn to the city’s own literature on its green spaces. Official documentation from colonial governments is ripe for theft and remixing. It is amazing how reframing a text can radically alter its meaning, and sometimes you don’t even need to change a thing. Repeating a text back to its original speaker can be a very powerful mirror and form of criticism. It can be very generative to just start copying some official text and to spend some time looking through it, over it, under it. Try to see something behind the words that function as a façade presenting the city’s vision for itself. Use the text to see the city for what it is to you. In some ways this is very much a type of play, and I find it very helpful to treat it that way, to approach the work in a tongue-in-cheek way. I wrote an entire page about the city’s golf courses this way.

As I mentioned previously, I had been thinking a lot about the Royal Mayfair Golf Club and its impact on the city. Golf courses produce a tremendous amount of chemical runoff that can endanger waterways and wildlife through excess fertilizer nutrients. Alberta Health Services issued a blue-green algae warning for Hawrelak Park Lake in 2020, cautioning that it can lead to health issues. Blue-green algae blooms are more likely to occur in lakes surrounded by significant fertilizer runoff, and Hawrelak Park Lake sits just downhill from the private Royal Mayfair Golf Club. The lake has been home to some marquee events, including frequently hosting the World Triathalon Grand Finals. The lake’s toxic algae put the hosting of the swimming event in jeopardy.

The city also owns its own golf courses and has some particularly interesting written material on its website. For example, it might be quite generative to consider the availability of public spaces dedicated to golf, which can be a very class specific hobby, in light of phrases used to describe one of the city golf league memberships as open to those “employed and self-employed”. Not all of public spaces are for all of the public.

But as interesting as it is to write about how golf is problematic, since this piece was about the names of parks, I thought I’d look more closely at that, and I set aside the page I wrote on the city’s golf courses.

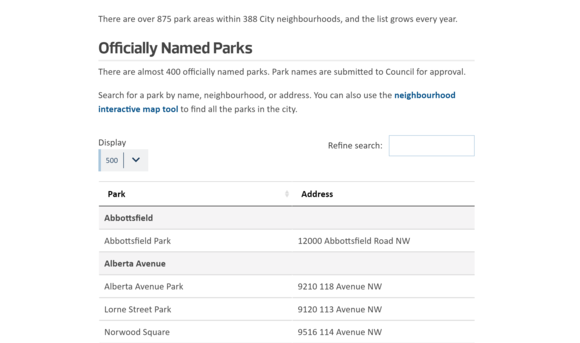

The city website has a handy list of its parks. Although the city has “over 875 park areas within 388 City neighbourhoods, and the list grows every year”, there are just under 400 officially named parks. “Park names are submitted to Council for approval.” By setting the list to display 500, I can get a full page of all the city’s named parks. A simple copy and paste spits out a table, and with some modifications I can remove the addresses, put all the park names in lower case, and remove the word ‘park’. Now I have a document that’s just all the names, in a list and ready to use however I end up using them.

What started out as just a list on a city website, conceptually reframed in the context of a critical look at public space, names chosen by a colonial government become more than just words on a page.

Look out for part three where I’ll show you how I use a suite of creativity software to put the pieces together.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Matthew James Weigel is a Dene and Métis poet and artist. He is the designer for Moon Jelly House press and his words and art have been published in Arc, The Polyglot, and The Mamawi Project. Matthew is a National Magazine Award finalist, a Cécile E. Mactaggart Award winner, and winner of the 2020 Vallum Chapbook Award. His chapbook It Was Treaty / It Was Me is available now. Whitemud Walking is his debut collection.