Friday Night Fright Club

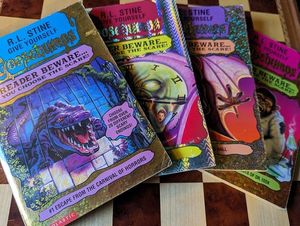

I didn’t vote for this. Remote viewing a friend’s funeral was not how I expected two years of reading Goosebumps live on the internet to end, but sitting next to my partner Emma in my office and staring through my computer screen at Amelia’s casket, I felt the loneliness of the whole pandemic punch me in the chest. I tried not to think of the parallels between this grim occasion and all the fun we’d had using this same kind of technology. The better ways we interacted in the blue light of our screens. The cruelty of a woman dead by cancer at 32 only seemed to amplify how absurd it was that for the past two years we pretended to perish a million different ways by democratically navigating R.L. Stine’s Give Yourself Goosebumps series of interactive children’s novels.

Amelia was there from the start. In March 2020, feeling the cabin fever of early pandemic pinching the edges of my brain, I tested the waters on Facebook: “If I were to host a live Instagram reading of a ‘You Choose the Scare’ Goosebumps book, where the audience votes on which decisions to make, would you join me?”

“Yes!” She responded in the comments. “Peter please do this! My apartment is so small!”

The idea was based on something my brother and I used to do when the power went out in our old Toronto apartment. We’d light candles and grab the choose-your-own adventure-style horror books from the shelf, then take turns reading in dramatic voices and collectively deciding on the best decisions when the narrative split. More than once, the electricity returned and we flipped the lights back off so we could finish the story. Reading together was fun. It was that simple.

Adapting the tradition to social media felt natural. I positioned my phone so I was in frame, lit by candles in a pink wingback chair, and hit the “Live” button on my screen. Emma sat nearby on the couch, having agreed to moderate the chat and tally votes, which I solicited by giving the viewers keywords to text-in, indicating their desired narrative course of action. If you want to investigate the howling on the wind, text in 1-GINSBERG.

The first night was a success, so we agreed to to do it again. Then again. Friday after Friday, we gathered around our phones in our small apartments and read together. Sharing our experience, reaching through the screens and giving each other those hair raising chills.

As a collective, we voted ourselves to death after death. The freefall starvation of a bottomless pit in Night in Werewolf Woods. The living entombment in Diary of a Mad Mummy. The human testing spattered through The Deadly Experiments of Dr. Eeek and the various fatal time paradoxes of Tick Tock, You’re Dead!—our morbid readings anchored us to community in our loneliest days. Summer came and went. The darkness of winter grew, threatening a terrible monster mash of seasonal depression crowned with pandemic isolation. But our Friday tradition fended off that beast, kept us aware of what day it was, and that we were part of something bigger than ourselves. In a time of worklessness, we resurrected TGIF with the help of R.L. Stine. Thank Goosebumps It’s Fright Club.

The limitations of the livestream medium—the inability to share reading duties, the necessity of a host and moderator—became features. Through repetition and necessity, a Fright Club structure evolved, and it provided a playground for viewers to build a Rocky Horror-esque set of rituals and icons. My misreading of a character’s greeting in Dr. Eeek led to the collective understanding that the main character was the same person across all 42 books, and that his name was Yoohoo. The audience approval of companion characters was met with calls to make out with them (never an actual voting option). And in Beware the Beastly Babysitter, when we saw Yoohoo transformed into a rodent and conscripted into “the Rat Peoples’ Army,” the audience self-identified in a fevered stream of text.

- “OMG I am SCREAMING!”

- [Rat emoji. Fist emoji.]

- “This is a good ending actually. Solidarity to my comrats.”

From then on, the Fright Club was synonymous with the Rat People’s Army. A flag was made and uploaded to Threadless and Teepublic. Printed on stickers, beach towels, and even skateboards. The inside jokes became outside objects.

After the first year, we made a Fright Club Zine, filled with art and puzzles from rat-people conscripts around the country and an original Choose-Your-Own-Adventure story. Our connection through the screen affected the real world, touching each other’s lives in isolation. At the end of each reading—signalled by either three bad endings, one good ending, or a reading that threatened to take us past the two-hour mark—we signed off with a collective howl in the name of giving those folks around us goosebumps, too. Just like everything we did together, it was inspired by some bizarre construction in the pages of Stine:

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“How-ow-ow-owl!”

Another year passed. We collected every book in the series and read them all twice. Then we called it a night. The power was back, and there were many reasons to turn on the lights. People were safer outside now. They had jobs again, and social lives off screen. The pandemic wasn’t over but the loneliness was, and for me that was what we were fighting. In the final days, when Amelia was in the hospital and I stopped seeing her name in the chat, I felt vulnerable to all the terrible things this reading group had kept at bay.

The pandemic restrictions flattened our experience and turned us into observers of our own interactions. That’s why Fright Club worked: it gave us a reason to participate in what we saw. The community influenced the votes, which in turn decided the narrative, which I read into the internet, allowing R.L. Stine’s horrific words to shake us back into three dimensions. We shared all the most gruesome demises together—wasting away in the brig of a cruise ship, mutilated beyond recognition by an evil birthday clown. We took the loneliest things on the planet, death and the internet, and used them to feel a bit more alive. Across impossible distances, we howled together.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.