Kids' Books - More than just learning to read

Submitted by Wendy Orr

In my previous life as a pediatric occupational therapist, I’ll guarantee I was never asked, ‘Do you think you’ll ever work with real patients?’ But as a children’s author, I’m equally sure I’m not the only one to have fielded the question, ‘Do you think you’ll ever write a real book?’

So the end of Children’s Book Week seems a great time to talk about why children’s fiction is not only real but important – and also why I love it.

There’s actually a lot to love, but I’m guessing anyone following this blog already knows that reading to babies helps with bonding; reading to toddlers benefits their success in school, and engaged readers tend to be more successful in later life too. You probably know that children’s books today are a rich and varied world, and that reading them offers much more than later success in school and business.

I’ve written picture books and early chapter books, a YA novel and even one proper grown-up one, but my passion is Middle Grade literature.

Ironically, I don’t think I’d ever worked out exactly why until I was asked the question on a Junior Library Guild panel last year. ‘Because eleven and twelve-year olds are so smart and capable; you can deal with lots of emotions but their not being overlaid by sex keeps the focus more on what’s happening. Still half believing in magic, these readers engage easily in a willing suspension of disbelief. A plot can be complex and multi layered or simply lots of fun; language playful or as rich as you want.’ That was my spiel, and it’s still absolutely what I believe.

But someone else – the other panel members were Dan Gutman, Sarwat Chadda and David Levithan, and apologies, I can’t remember now who said it – chose hope as the element that makes this genre special. No matter how dire the adventures, how grim the setting or true the grief, a middle grade novel needs to end with a strong glimmer of uplifting hope. I’ve always done this instinctively, but had never identified it as key until the light bulb moment of hearing someone else say it.

Readers in this age group – generally eight to twelve, though my Bronze Age Minoan Wings series is often suggested as being for ten to fourteen – throw themselves into a novel with whole-hearted passion. The younger ones often think the story is real, no matter how fantastical it seems to an adult. Can I visit Nim’s Island? I’m often asked, or, Can I be Nim’s friend?

However, what I love best, and what adds the greatest responsibility to writing for this age group, is how fiercely they can identify with the protagonist. Studies show that children who read more fiction score higher in empathy; I’m guessing that one of the reasons is that stories let us identify with many more different lives than we could ever hope to encounter in real life. They also cut out the extraneous details, peer pressure or parental prejudice involved in befriending someone very different to ourselves at school or sport.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

It also seems pretty clear that it’s essential to start developing this ability to ‘walk in someone else’s shoes’ as early as possible. (I’m sure the choice of that cliched metaphor is from a particularly strong memory of being curled up on the couch in our home in Red Deer when I was nine or ten, reading about Napoleon’s soldiers trudging and dying in the snow on the retreat from Moscow. I have no idea what drew me to this book, but remember desperately wishing I could walk a few miles for the soldiers, because more of them might have lived if they’d had a rest. And I mean desperately – I can still remember the gut-wrenching feeling of it. )

If children identify that deeply with fictitious characters, they’re probably learning from them too. I don’t mean morals – another question that makes me froth at the mouth is, What are the morals of your books? as in Will this book teach my child to obey me? Sorry - probably not. But think for themselves? Possibly.

The involved reader borrows the protagonist’s strength and courage as they struggle through the trials a malevolent author has set them, building up resilience. It doesn’t matter if the fictitious character is facing bulls or bullies, plague gods or an all too real pandemic, middle graders can generalise the problems and identify them with their own difficulties. And when they reach that glimmer of hope at the end, they can borrow that too. Resilience and hope – we can go a long way on those, no matter what life throws at us.

As a twelve-year old boy said after reading Dragonfly Song, ‘I wanted to try out for the soccer team but when I got there I was too scared. I walked back across the field and suddenly thought about Aissa and how brave she was with all that she went through. I’m going to try again next time.’

Kids’ books – they’re about more than just learning to read.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

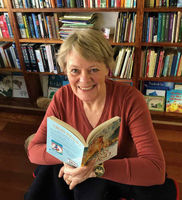

Award-winning author Wendy Orr was born in Edmonton, Alberta. The daughter of an Air Force pilot, she has since lived around the world, including several years in Colorado, in France, and England where she studied Occupational Therapy. After graduation, Wendy settled in Australia, but returns home yearly to visit her family. Wendy’s many books for children have been published in 27 countries and won awards around the world. Prominent among them is Nim’s Island, which was made into the 2008 film of the same name; a 2013 sequel, Return to Nim’s Island, was loosely based on Orr’s book Nim at Sea.