The Writer's Voice: It's Not What You Say but How You Say It

Submitted by Wendy Orr

‘It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.’ As a child and teen I heard this simply as a parent’s retort to the self-righteous whine, ‘But I only said…’

As a writer I realise it’s one of the most basic guides to writing. If it’s true there are a limited number of plots for a story, it’s even more true that there are an infinite number of ways to tell it, because each of us will tell it in our own voice.

So what is a writer’s voice, and how do we find ours?

I see it as the particular way in which we create unique stories and characters: a blend of our personalities with the craft of writing – cadence and syntax, word choice, punctuation, alliteration and sentence length. It overlaps style, although style can change dramatically in different works while voice stays true from genre to genre. A French friend, whom I’ve known since we were five and who speaks no English, told me that she loved hearing my voice in the French translation of Nim’s Island. Something in the way we speak and write holds true through language differences, conversation or written text.

I suspect the author’s voice, like everyone else’s, starts at birth or even in utero, with the cadence and tones of the first voices we hear. Who knows how many of those earliest newborn adorations have been handed down, mother to baby, through the years like mitochondrial DNA? Is it like the vocal harmony of sibling singers?

As we grow, so do our voices. Mine was laid down, not just through what my parents read, sang and said to me in English, but in the conversations, songs and stories that my friends and I shared in French. It was influenced by a childhood identity of being a storyteller, by a young adult habit of weekly letters to my parents, and perhaps most importantly, by the inner dialogue of the stories I’ve always told myself, both as conscious fiction and that deep, often buried, ordering of life events and memory. We all do the latter, though writers may be more overt in bringing it to the surface.

Which suggests that an author’s voice reflects in a very profound way, some of the depths of our subconscious that our books unwittingly share with the world. For me, it’s the belief in resilience, hope, quiet strength and courage – the knowledge that we can survive and even thrive, no matter how terrible the blows life deals us.

But I can’t help wondering if the injunction to, ‘find our voice,’is actually counterproductive. It might be better to stop worrying about where our voice comes from and listen to the work. If we tell each story the way it wants to be told, our voice will find its way through.

I often hear my stories in free verse before I start, though until Dragonfly Song, have always written them in prose. This story, however, refused to be narrated in anything but blank verse. The thought terrified me, partly because Bronze Age setting seemed too complex to be told this way, partly because I’d never written a verse novel. I tried to force it into prose but it wasn’t the book I wanted to write. Finally the story and I reached a compromise: a combination of poetry and prose. In fact, I wrote most of it in verse – especially when deadlines loomed – and later transposed some sections into prose.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

So why didn’t I just write these Minoan Wings novels completely in verse? Because my first feelings about complexity were valid; the stories needed changes in tempo, a more prosaic tone or a wider point of view for some scenes. Basically, I had to trust my own voice and not just the story’s.

And how to get to that point?

1) Read, read, read. Don’t worry about other authors’ voices affecting yours – they’ll be composted into a rich soil that will help you grow confidence in your own. Read favourite passages aloud.

2) Write, write, write. Experiment with different styles and genres. Be honest with yourself about what you’re enjoying or not – don’t judge. You might be surprised at which ones are fun.

3) Shut down your inner critic in first drafts. Give yourself permission to make mistakes.

4) Try writing the first draft by hand instead of typing.

5) Read your drafts aloud.

6) Be patient and have faith in the process.

No matter what logic we use to tame and style it, our voice comes from the subconscious, that dark and mysterious mess of who we are. It may be deeply buried by conventions and perfectionism, but it’s there, as unique as we are. The writer’s gift is to find the confidence to use it.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

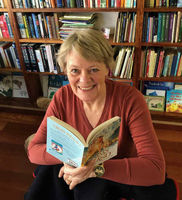

Award-winning author Wendy Orr was born in Edmonton, Alberta. The daughter of an Air Force pilot, she has since lived around the world, including several years in Colorado, in France, and England where she studied Occupational Therapy. After graduation, Wendy settled in Australia, but returns home yearly to visit her family. Wendy’s many books for children have been published in 27 countries and won awards around the world. Prominent among them is Nim’s Island, which was made into the 2008 film of the same name; a 2013 sequel, Return to Nim’s Island, was loosely based on Orr’s book Nim at Sea.