Daniel McNeil Examines the Figure of the Black Public Intellectual Through the Lives of Armond White and Paul Gilroy

American film and music critic Armond White and British cultural studies scholar Paul Gilroy are two larger than life figures—widely celebrated but also controversial—in the fields in which they've both become essential voices. They also, as Black men, occupy a unique space in those sectors.

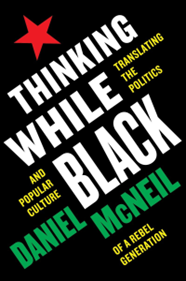

Dr. Daniel McNeil, a professor at Queen’s University and the Queen’s National Scholar Chair in Black Studies, explores these two men and their impact in Thinking While Black: Translating the Politics and Popular Culture of a Rebel Generation (Between the Lines Books).

Though White and Gilroy live an ocean away from one another, McNeil deftly winds the threads of their lives together as he examines their influence, the reactions their writings and research elicit, and their treatment and movement within their rarefied cultural spaces. Drawing on politics, pop culture, and film theory, Thinking While Black charts a history through cultural movements of the late twentieth century, the evolution of Black voices in film and culture, and more. McNeil also reveals how creative artists such as Bob Marley and Toni Morrison inspired White and Gilroy to draw thoughtful and insightful conclusions about what cultural spaces and commentators can tell us about identity, racism, and the character of a country.

We're speaking with McNeil about Thinking While Black as part of our nonfiction series, the True Story interview. He tells us about how Gilroy and White can be seen as mirror images in a sense (with the former serving as a academic and occasional journalist and the latter as a journalist and occasional academic); what he learned from spending time in person with each of the two men; and how he hopes the book will "carve out a bit of space" for people to broaden their understanding of the idea of a Black public intellectual.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be. What made you passionate about the subject matter you're exploring?

Daniel McNeil:

Thinking While Black is a book about the work and ideas of two celebrated and controversial writers who have invited and challenged their readers to do some deeper and fresher thinking about politics and popular culture. It pays particular attention to the prominent British intellectual Paul Gilroy, the notorious American journalist Armond White, and a political and cultural generation that came of age in the 1960s and ‘70s consuming rebel music, revolutionary film, and other forms of expressive culture created by world citizens and the descendants of enslaved individuals.

The first part of the book tells the story of young soul rebels who struggled and organized – often outside of conventional politics – to rock against racism in underground newspapers and social movements during the 1970s and early ‘80s.

The second part re-examines debates in the 1980s and ‘90s about artists who “spread out” to impose their vision on the world without sacrificing difficulty or “selling out” with cheap thrills, unedifying entertainment, and exploitative material. It is a tale of two critics in New York and London who sought to push professional and routine discussions about race relations into livelier and more radical reflections about Black consciousness, planetary humanism, and a world without racial hierarchies.

The third and final part of the book considers the late style of writers who have been celebrated and condemned as eminent intellectuals and curmudgeonly contrarians in the twenty-first century. It thinks with and through Gilroy’s claims that Black music has lost its moral authority and is in decline, and White’s repeated sorties against what he considers the unimaginative, infantile, and overhyped cultural content that reflects and intensifies the regression of film culture.

When I first encountered the work of White and Gilroy as a graduate student at the University of Toronto in the early 2000s, I found it incredibly striking, vexing, and stimulating. Wrestling with the “forbidding abstraction” of The Black Atlantic in a comparative history seminar left me with many questions about the language and style of a book that Gilroy wrote in search of a “proper job” as a scholar. Yet the academic phrases that are such a feature of one of the most cited and influential works in Black Studies, (“it bears repetition”, “what I am calling”, etc.) didn’t prevent me from also appreciating the open, creative forms of expression in the book. Similarly, I was taken aback by White’s exacting standards and provocations when I stumbled across one of his articles for the New York Press in a cramped computer room reserved for graduate students, but I consistently checked out his reviews to learn more about humanistic filmmakers and the principled stance of a journalist who rejected the idea that his reviews needed to be pitched at a sixth-grade reading level.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I drew on intriguing passages and concepts in the work of both writers to develop articles and books about the prurient interest in mixed-race identities, the “slightly condescending, old-school liberal slant” of the Canadian film director Norman Jewison, the post-imperial melancholia of the British politician Enoch Powell, and the carefully constructed public persona of the American film producer and politician Barack Obama. However, the impetus to write a book about the two critics and their political and cultural generation was probably sparked when I read an interview conducted in 2008 that included a striking passage in which Gilroy claimed that the person who wrote The Black Atlantic no longer exists.

Gilroy might not have intended the comment to be taken literally, but it led me on a quest to think about what it might mean to write a story about the life and death of Gilroy-the-author-of-The-Black-Atlantic (a secular Stations of the Cross about the grind of research and writing, the extensive and sometimes vitriolic criticism of the book and its author, the changes in his material circumstances as he became a Professor at Goldsmiths and then at Yale, and so on.). It also prompted me to consider how I might address the gap in the academic literature about the person who existed before the writing of The Black Atlantic and was juggling work as a lecturer, journalist, and research officer for the militant Greater London Council.

To explore how Gilroy combined his career as an academic with a supplementary career as a journalist, it seemed helpful to place his work in dialogue with White, who has had a long career as a journalist and only occasionally taught classes on film history and culture to university students. I was concerned that a book that just talked about the work and ideas of Gilroy – whose impact on multiple academic disciplines is well-known and celebrated with distinguished awards such as the Holberg Prize – might overlook or obscure the distinctive challenges faced by Black intellectuals who encounter media institutions and editors who expect and demand accessible, quickly produced content. If it just focused on White – who can be a bit dismissive about “academic eggheads” in his reviews of film and culture, and was expelled from the New York Film Critics Circle in 2014 by journalists who believed that he had failed to uphold “the integrity and significance of film criticism” – the distinctive challenges of navigating academia as a Black intellectual might be ignored or marginalized.

OB:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

DM:

I first encountered the work of White and Gilroy when the independent print media was receiving palliative care. So, I relished the opportunity to immerse myself in archives that communicated the liveliness and vitality of counter-cultural newspapers in the 1970s and 80s that had inspired young soul rebels to imagine and build an intellectual life.

I went off to Detroit to consult the archive of the South End, the student newspaper of Wayne State University that was transformed into an imaginative vessel for the Black radical tradition after the Great Rebellion in Detroit in 1967. White wrote for the South End between 1972 and 1977 when it was no longer associated with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. However, it continued to offer readers a “viable and refreshing alternative to the drivel of the establishment bourgeois press which is the lap-dog of the ruling class,” and White was praised by his colleagues for refusing to submit to the demands of “consumer or entertainment conglomerates.”

In archives in New York and Chicago, I read thousands of articles White wrote between 1984 and 1996 for the City Sun, a Brooklyn-based Black newspaper with the tagline “speaking truth to power”. In addition to such unfiltered reviews of music, film, theatre, and other forms of expressive culture – in which White sought to circumvent and transform the dominant values of a straight, white, middle-class world – I also checked out incredible conversations hosted at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts during the early 1990s. It was particularly revealing to witness White participate in a discussion about the role of the arts editor with his colleagues at the Village Voice and New York Times. I learned a lot from dusting off a VCR in the New York Public Library and seeing White respond to the flowery bohemianism and tweedy self-importance of his fellow journalists by proclaiming, “I can’t be bought”!

To get a better sense of Gilroy’s contributions to counter-cultural publications, I travelled to archives in the UK and US. I actually ended up reading the work he published in City Limits (an arts and events listing magazine in London that broke away from Time Out magazine when its owner abandoned the publication’s original cooperative principles and imposed changes to its collective working practices), in Cambridge, Massachusetts rather than Cambridge, England! Reading these reviews, concert previews, and interviews for City Limits – which would be published alongside advertisements for Irish freedom festivals, conferences on socialist economics, and other initiatives that demonstrated the interrelationship and interdependence of cultural production and radical politics in the 1980s – in the rarefied settings of Harvard was also helpful in addressing some of the ironies, tensions, and frustrations Gilroy worked through when he became a Professor at Yale in the early 2000s (as well as his concerns about North American voices drowning out everyone else in purportedly transatlantic or global conversations).

The book was also transformed and boosted by conversations with Armond and Paul that discussed articles from their time at the South End and City Limits, and their journeys of intellectual discovery over the past half-century.

Walking around New York with Armond was extraordinarily helpful in deepening my understanding of his approach to politics and popular culture. I witnessed, for example, how the 6-foot-3 critic gracefully responds to New Yorkers who are bullied and encouraged by journalists to assume that Black men of his size are “imposing” or predisposed to violence. Such observations added important context and nuance to my reading of his critiques of performative activism and contemporary campaigns to root out microaggressions.

Similarly, my conversations with Paul helped me think about his capacity to read the signs in the street in defiance of so many middle-class professionals who only see the world through the windows of their cars, taxis, and ride shares. It’s rarely discussed in polite academic circles, but many of the profiles of Black public intellectuals that proliferated in the United States in the 1990s drew attention to the “fancy cars” of Cornel West, Henry Louis Gates Jr, and bell hooks.

I hope that the book carves out a bit of space for people to talk more about the structures and signifiers that reduce the term “Black public intellectual” to “African American writers with ties to Ivy League universities and/or prominent newspapers and magazines based in New York.” After all, one of the things that drew me to the work of Armond and Paul as a user of Toronto’s public transportation system in the 2000s was their openness to communicating the insinuating rhythms of everyday life. I appreciated how Armond’s reviews called out inauthentic portrayals of New York City subway operatives. I also valued Paul’s ability to carefully observe the language and style of his fellow Londoners on buses and trains. I liked their refusal to take the overdependence on the car and the obeisance to car culture, for granted. I shared their interest in the informal and extra-institutional spaces in which intellectual life and revolutionary curiosity might flourish. And I wanted to think and write about other public spaces and independent institutions (such as libraries and broadcasters) that offer a bulwark against authoritarianism, alienation and overconsumption.

OB:

What are you working on now?

DM:

I’m currently working on a couple of things. I’m producing and co-hosting the Black Studies Podcast, which brings together scholars, activists and artists to discuss creative and collaborative knowledge-making that engages the arts, social justice and decolonial thought. I’m also collaborating with colleagues on knowledge exchange projects about the global intellectual history of social movements and a research handbook on multiculturalism.

_________________________________________________

Daniel McNeil is a professor at Queen’s University and the Queen’s National Scholar Chair in Black Studies. His scholarship and teaching in Black Atlantic studies explore how movement, travel and relocation have transformed and boosted creative development, the writing of cultural history and the calculation of political choices. He is the author of Sex and Race in the Black Atlantic (Routledge, 2010) and, with Yana Meerzon and David Dean, a co-editor of Migration and Stereotypes in Performance and Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). He lives in Tkaronto/Toronto.