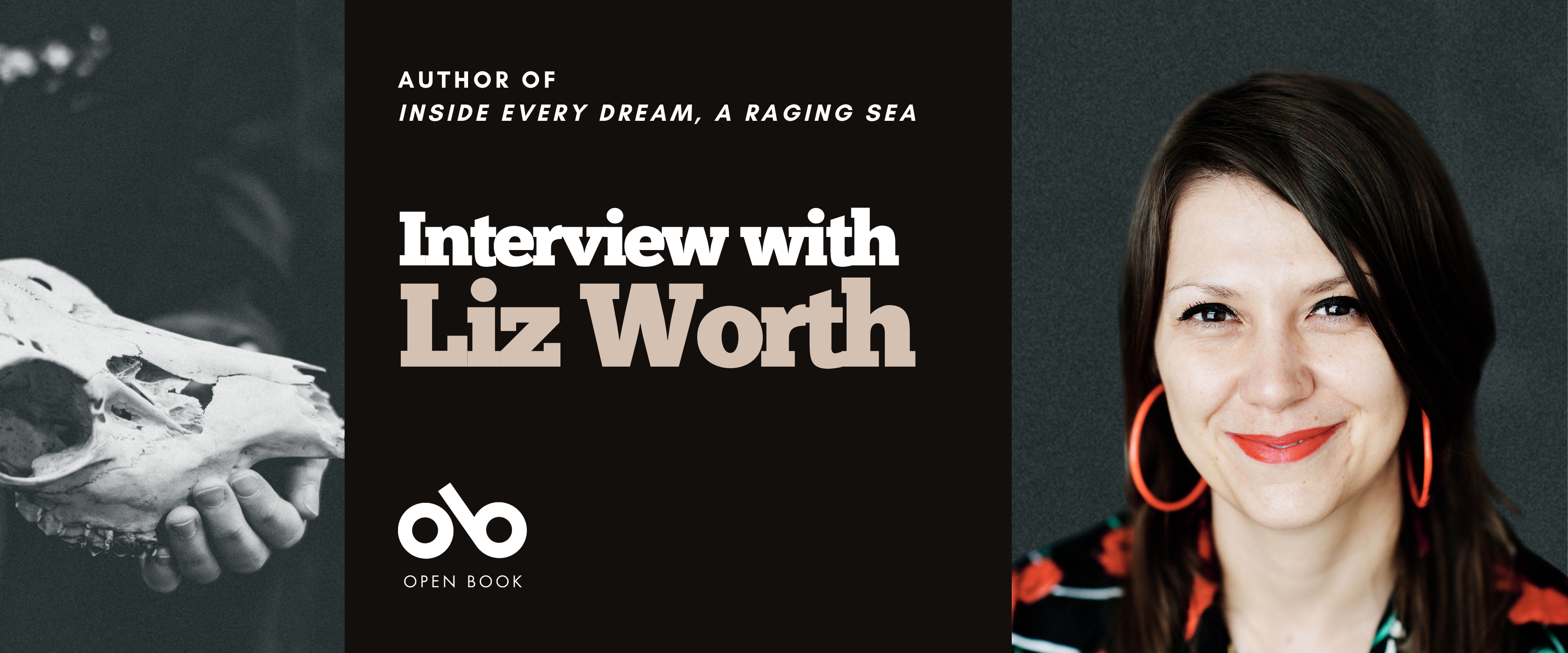

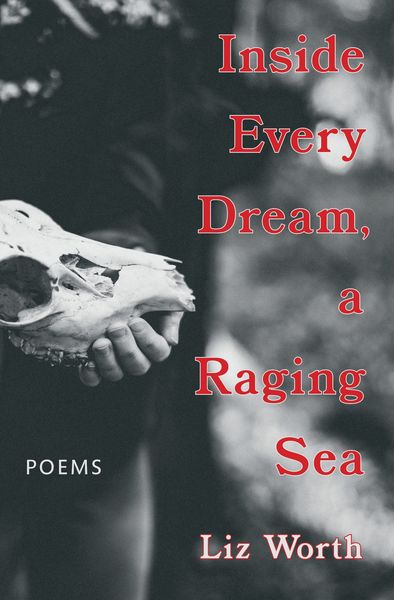

Liz Worth Explores a Poetic Life and the Mysteries and Truths That Abound in Her New Collection, Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea

Acclaimed poet Liz Worth has long been involved in the independent lit and poetry scene in Toronto (and now in Hamilton), finding her way into the community after a fortuitous encounter on the street. Since then, she has published a haul of books, and her writing has appeared widely in magazines across the country.

Worth has always looked to themes of the mysterious and the Occult (she is also a professional Tarot card reader), and her latest work, Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea (Book*hug Press) delves deeply into the strange and haunted lives that people lead, filled with personal legend and hidden meaning that can be found when we blur the lines of the known and unknown. The poems in this collection confront uncomfortable truths about age, regret, and identity and show an openness to explore all of the possibilities in our worlds.

We have a riveting Poets in Profile Interview with the author to share today on Open Book, where Worth talks about her origins as a poet, the joys and toils of a poetic life, and the process of writing that has served her over an already storied career.

Open Book:

Can you describe an experience that you believe contributed to your becoming a poet?

Liz Worth:

I got interested in poetry at a young age. There were several factors that drew me to poetry as a kid: It seemed to hold a type of mysticism that I found intriguing.

I don’t know if I would have pursued the path of poetry to such an extent if I didn’t feel that the external world was nudging me toward it, too, though, through various synchronicities.

One of the strongest instances of this happened when I was 17. I was publishing my own poetry zine. I was living in the suburbs and was actively looking for poetry readings to perform at. But it was the ‘90s and it wasn’t always easy to find out about events if you didn’t know where to look.

I was walking down Spadina Avenue in Toronto with my boyfriend at the time. I had just been talking to him about how much I wanted to find a poetry community and start attending readings when a guy came up to us and said, “Hi, do you like poetry? We’re doing an open mic next week.” And he handed us a flyer with all the details.

That was a highly synchronous moment for me, and one that helped me hook into the literary community in Toronto.

OB:

What is the first poem you remember being affected by?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

LW:

It wasn’t just one poem so much as a collection for me, that being Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T.S. Eliot.

I was obsessed with cats as a child and, having grown up in the ‘80s, was very much exposed to the hype around the musical Cats by Andrew Lloyd Webber, which I begged my parents to take me to for my Grade 5 graduation gift.

Cats is based on T.S. Eliot’s poems, which I thought was brilliant, and Eliot’s book was one of the first book of poems I bought for myself. I loved the world-building taking place in those poems as well as the versatility of those pieces. To see that poetry could be reinterpreted into a sprawling musical was highly inspiring. It made me look at art as something fluid and flexible, always evolving, rather than static and binary.

OB:

Do you write poems individually and begin assembling collections from stand-alone pieces, or do you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

LW:

My work so far has consisted of both, though the former situation has dominated my process overall.

The one exception was when I wrote No Work Finished Here: Rewriting Andy Warhol, which was a poetic appropriation of Warhol’s a: A Novel. That book had a clear, singular goal from the start – to rewrite each page into a poem.

Otherwise, most of my poetry begins with a small idea. I’ll start with an incongruent pairing of words, or an image. Most of these come to me spontaneously, usually while I’m walking. When I sit down to work with them more intentionally, I give those ideas shape through the filters of my stories: My memories, my feelings. Whatever feels necessary to evoke at the time.

Most of Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea came to me on walks, so much so that I wasn’t even aware I was working on a new collection. I would come home with a head full of lines, write them down, and then work them into something cohesive.

That went on for about two years. It was only when I looked through my notebook that I realized I had a substantial amount of new work skirting along shared themes.

OB:

How would you describe the poetry community in Canada? What strengths and weaknesses do you observe within the community?

LW:

I have always felt that Canada is home to many amazing writers of all kinds. There is something special about the way we write here.

The poetry community itself offers a wide range of perspectives, voices, and approaches. I think that is both a strength and a weakness, especially when so many opportunities for poets are set against conventional literary merits. Where do you fit in if you’re not creating work that fits with the literary standards? And who sets those standards, anyway?

Where do you fit in if you are offering an alternative if there isn’t an easily identifiable category (or opportunity) for you to be slotted into?

Another challenge is that it’s hard to bring new audiences in. Very often it feels like poets are writing and performing for each other. At literary events the rooms are often filled with other writers, both aspiring and established.

If the public at large isn’t willing to investigate poetry more often, how do we change that? How do we broaden our audience collectively? How do we get more people engaged in the work?

How do we help people to see that they can find themselves in poetry the same way they can in a novel, or a memoir?

OB:

What is the best thing about being a poet…and what is the worst?

LW:

Poetry offers a tremendous sense of creative freedom. You can push the boundaries of language, form, style over and over again and all you need is a pen, paper, and a little bit of time.

You can stay in a state of constant inspiration as a poet, which to me is one of the perks.

OB:

What is the worst thing about being a poet?

LW:

A lot of us toil in obscurity. There is a lot to come up against as a poet if you want to have some kind of career here. And I don’t even mean that in a highly commercial sense: Just getting published as a poet is a huge deal. It’s one of the most competitive writing markets with one of the smallest audiences.

And finding your audience takes a lot of time. This a path that requires patience and perseverance. You have to be very dedicated to the craft. It’s not easy to get the everyday reader to support poetry.

Heck: It’s not even easy to get your friends to support you as a poet sometimes. The constant battle to even pique someone’s interest in poetry might be the hardest part of it all.

______________________________________________

Liz Worth is a poet, novelist, and nonfiction writer. She is a two-time nominee for the ReLit Award for Poetry for her books The Truth Is Told Better This Way and No Work Finished Here: Rewriting Andy Warhol. Her first book, Treat Me Like Dirt, was the first of its kind to provide an in-depth history of Southern Ontario’s first wave punk movement. Her other works also include Amphetamine Heart, PostApoc, and The Mouth is a Coven. Her writing has appeared in Chatelaine, FLARE, Prism, the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, and Broken Pencil, among others. Liz is a professional tarot reader and lives in Hamilton, Ontario.