Read an Excerpt From Balsam Karam's Lyrical, Breathtaking Novel, The Singularity, Translated From Swedish

Widely acclaimed in Sweden, Balsam Karam is an author who has already been recognized for her craft and storytelling, with her latest novel shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature, the August Prize, and Svenska Dagbladet’s Literature Prize. Her work is an intense exploration of grief, migration, displacement, and profound loss, exciting and challenging readers with its ambitious, inventive prose.

In her new novel, The Singularity (Book*hug Press), Karam takes us to an unnamed coastal city, full of refugees and lost children. We follow the stories of two women; a mother who searches desperately for her daughter and displaced family until she can't bear the grief anymore, and another woman on a business trip who witnesses this mother's fate. As the second woman's life unfolds, she suffers her own profound personal losses, and ruminates on the loss of language, country, and identity in the wake of her family fleeing a distant war.

This is an enthralling and challenging novel, written by an author of Kurdish ancestry who deftly decenters a white European gaze while working from Sweden. Balsam Karam is an artist to follow and admire, which is why her books have made waves internationally.

Today we're sharing an excerpt from The Singularity, chronicling the day-to-day lives of some of these lost children in Karam's unnamed city as they wait in the alley that they call home. Waiting for something to happen, and for someone, anyone, to come for them.

Excerpt from The Singularity by Balsam Karam, translated by Saskia Vogel:

One Friday morning in the city where cars big and white are parked along small streets and carts knock them dented and dull, yet another mound of trash grows larger with all that no one knows what to do with anymore.

At the end of the day the men walk up to their cars, run their hands over the new dent nearest the headlight, and search the street; the men search as if they now might run into the responsible bread or juice vendor, and before they drive away as they do every day, they approach the cigarette vendor across the street and ask if he has seen anything. My car got bashed, the men say—did you see who did it? they ask, still wearing their sunglasses.

The cigarette vendor shakes his head, then goes back to reading his newspaper.

The children see the white cars driving and sometimes sit down to count them, up to sixty or seventy before they tire and again shut their eyes in the morning sun vast across the alley.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Here is the slowness and the endless heat, the trash blown in and left behind, and the children’s increasingly emaciated bodies, their small repeated movements across the alley; here is the dust and the drought, but no longer the smell of laundry hanging from lines so low the children must duck under, and neither a friendly pat nor a song to sing to pass the time; along the walls there are no longer bowls of washed rice or yellowed paper for the children to paint, nor is there a ball to kick or a pasture drawn on the faded squares laid across the alley.

As if the world were at a standstill and the days one and the same, the children sit open to the road and see all the passersby and how they observe them defeated as if in solitude or just anticipation in the alley.

The children no longer shield themselves when someone points at them and says something they don’t understand; they don’t turn away, don’t cover their face with a hand, and don’t hide their wounds, small swollen lines across their legs, when an observer continues down the pavement, leaving them as they were in the alley.

The children no longer call out Gran, I’m thirsty or there’s a rat at the ruined wall, what are we going to do about it? nor search the containers for flour and sugar and tea and coffee; they no longer collect the dregs of cooking oil at the bottom of glass bottles that haven’t yet broken; they hang no herbs to dry, keep nothing cold in a shade that no longer exists and do not sweep the dust out of the alley.

Once she came with me to the square to pick flowers for Gran’s birthday and on the way home we saw a kitten in the bushes under the palms. It was love at first sight and when I bent down to pet it an old man shouted from a balcony, said I wasn’t allowed and should leave at once. I remember how angry this made her and how she shouted something at the old man the children say. Then she picked up the kitten so I could cuddle it and when we were done we went back home the children say and toss a stone high in the air in the alley.

Yes, and another time she took me to the sea after we’d been selling washcloths at the market and once we’d finished swimming she said we were going to the corniche for ice cream and we both chose chocolate and when the people on the corniche saw us with our ice cream they called her over, but she was off that day so she said no and we didn’t go there and instead we came back home the children say in the alley.

The children don’t pick up cans to throw at the observers’ heads anymore so no one laughs when they miss or cheers for each bull’s eye; the children no longer pull back their slingshot or sling their stones and sing none of the songs they were taught as the mist above the metal roofs and the mountains eased and they assembled at the hillside to watch the starry skies more beautiful than ever.

Back then the Missing One would sometimes arrive at the hillside later, when everyone was already sitting with tea and bread and fruit and butter, waiting for the starry sky and the moon to appear; it happened, and just as she lay down tall and large among the children, they asked her if she had been in the schoolhouse arranging again. Have you? Have you been in the schoolhouse doing that thing you never tell us about? Minna asked and looked at her sister and at her sister’s hands and then but what are you actually doing there? as the blue of the heavens drew away and a new moon rose and can we come with you next time? at the very moment the mothers switched off the electricity powering the generator and the lantern went out and the whole hillside looked up at Orion and Virgo and the Little Dipper and the Plow.

The children play for a long time with the mountain and the homes and the labyrinths and the borders in the alley, and when the stones in their mouth draw blood they take a break. They take a seat at the ruined wall with the yarn no one crochets anymore and plait the strands into long snakes to toss out, then pull back, waiting for something anything to happen, shutting their eyes to the dust and light across the alley.

The children no longer know whether it is today or tomorrow that their mother will return holding their sister’s hand in hers, nor whether it was yesterday or a year ago that they were driven here with what little they were allowed to keep wrapped in blankets and sheets, a skirt large enough to carry pots and pans in, and two big sacks they later tore open and placed on the ground as a buffer to the cold in the alley.

The children don’t know if long ago they ran back and forth to the tent school and carried as many books as they could get their hands on before it was levelled to the ground, nor whether now is when they must once more line up before the people in military uniforms and with their mouths open wide feel those thick fingers searching their throats.

They no longer know whether it was before or after the people in military uniforms broke the water tap in two and pulled up the berry bushes and took away the lantern, nor whether it was at this moment or later that they filled the ditch with the demolished walls and tossed the tarpaulins in a pile beside.

Was it yesterday or a lifetime ago that they were instructed to stay here and wait like others have had to wait, for months perhaps years, and is it tomorrow that they will yet again be paid a visit by the relief organization that says hello and how are you all then here you go and we’ll be back soon, even if it’s not true?

The children don’t know, don’t remember, have no one to ask.

If you make a paper airplane, I can fly it over the ruined wall and the road the children say to each other and holdout a piece of newspaper that has blown into the alley—if you shut your eyes tight and count to ten the children reply and turn their ears tense to the ruined wall and the road.

Will someone finally find their way here and will they come into the alley?

Will they say they’ve bumped into the sister along the corniche or seen Mum sitting at the far end of the harbour, and will that person try to get the children to go there with them? Will the children rise from the dust and disappear and will someone search for them after they go?

Does anyone ever come here these days and if so, who? The children wait and listen, as usual barely moving in the alley.

___________________________________________

Excerpt taken from The Singularity, a novel by Balsam Karam, translated by Saskia Vogel, published by Book*hug Press. Copyright Balsam Karam, 2024. Reprinted with permission.

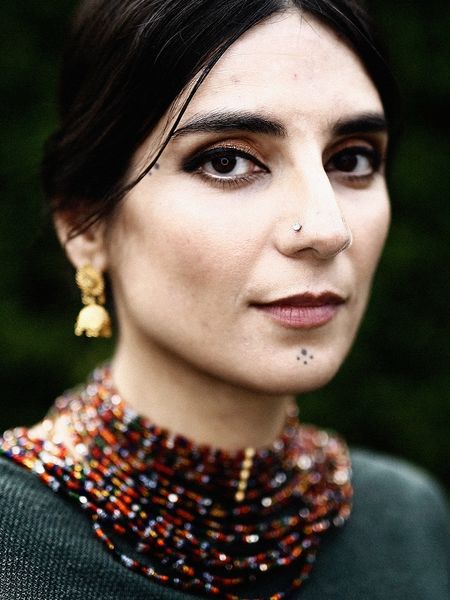

Balsam Karam is of Kurdish ancestry and has lived in Sweden since she was a young child. She is an author and librarian and made her literary debut in 2018 with the critically acclaimed novel, Event Horizon, which was shortlisted for the Katapult Prize and won the Smaland Literature Festival’s Migrant Prize. Her second novel, The Singularity, originally published in Sweden in 2021, was shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature, the August Prize, and Svenska Dagbladet’s Literature Prize.

Saskia Vogel is the author of the novel Permission and a translator of more than 20 Swedish-language books. Her writing has been awarded the Berlin Senate Endowment for Non-German Literature. Her translations have won the CLMP Firecracker Award for Fiction (Johannes Anyuru’s They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears), have been shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize (Jessica Schiefauer’s Girls Lost), and supported by grants from the Swedish Arts Council, the Swedish Authors’ Fund, and English PEN. She was Princeton’s Translator in Residence in fall 2022 and lives in Berlin.