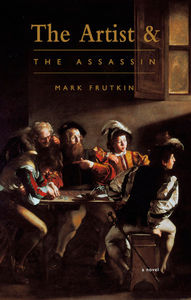

Read an Excerpt from Mark Frutkin's The Artist and the Assassin, A Retelling of Revolutionary Artist Caravaggio's Life and Death

Italian artist Caravaggio revolutionized painting in the 17th century with his dramatic use of light and shadow (a technique known as chiaroscuro). During his life though, his tumultuous personal affairs attracted as much attention as his revered artwork, with his fiery temper leading to street brawls, a murder warrant, and a flight from Rome to avoid prison time.

Mark Frutkin captures Caravaggio's turbulent story, one that still fascinates art historians to this day, in his new novel The Artist and the Assassin (Porcupine's Quill). And while art lovers will find an extra layer of delight in Frutkin's storytelling, the drama and suspense of The Artist and the Assassin will draw you in even if you can't tell a Rembrandt from a Raphael.

We're excited to present an exclusive excerpt from the novel today, courtesy of The Porcupine's Quill. Here we meet Luca Passarelli, ostensibly a model for Caravaggio. What Caravaggio doesn't know though is that the enemies he has earned have had enough, and Passarelli, a man with an even darker past than Caravaggio's own, has entered his life to act on their behalf.

Excerpt from The Artist and the Assassin by Mark Frutkin:

THE ASSASSIN

Rome 1600

I am the cloud in the sky and you, artist, the cloud’s shadow scurrying over the earth. I am the cloud over your shoulder, sailing through the heavens, encountering no resistance. I carry lightly the thoughts, the belief, of a man who has never known doubt, while you, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, are the shadow of the cloud on the earth, rolling up and down hills as you try to escape. Where cloud and cloud’s shadow meet will be your end.

He has me posing as a saint, me, Luca Passarelli, with a thief for a father and my mother a wet-nurse. To be precise, he wants me playing Saint Matthew. Matthew, the one called by Christ from the streets to his spiritual life as an apostle. I sit at a table in the vaulted cellar of a palazzo belonging to one Cardinal Del Monte. I’m waiting with the artist’s other models, several older louts and two young men, boys really, snappily dressed in silks, wealthy punks out slumming with the likes of us. The artist chooses to pose me as the apostle and saint. If you can imagine that. Me a saint. I would qualify for a saint’s vow of poverty, certainly, but not by choice. Me with my one set of worn, flea-ridden clothing—a shirt, a tunic, and a pair of hose with holes in the knees. I cannot afford anything else. He has made me up to look older than I am. And I am no Jew, though Matthew was.

Altogether, seven of us pose in this cellar. Two of the models stand across the room, representing Jesus and Peter. Christ himself is pointing at me. The rest of us sit around the table counting the coins I gathered as if we are preparing for a night of gambling. I am the focus. Me, posing as Matthew, known as Levi the Tax Collector in the ancient stories. The light shines on me, and on the young scamp to my left, one of the artist’s favourites, I hear. I wonder if he is bedding the boy? Could be. I wouldn’t be surprised, but I can’t say for sure.

Michelangelo Merisi, this artist from a little village called Caravaggio near Milan, stands across the room, gazing into his enormous canvas and working it, licking his brush before stabbing it again into his palette, and occasionally glancing out at us models posed around the table. His eyes are sharp, he bites his lip, he wears his thick, black hair longish in the front. Youthful style. A small window of this cellar is covered by a sheet of paper soaked in olive oil. I watched him early the first morning pour the oil over the sheet in a large pan. I could smell it. Expensive stuff. Enough oil for a family of six for a month.

The old guy sitting to my right complained on the second afternoon: ‘Why not make a quick drawing and let us out of here, finish the painting in your studio?’

Merisi didn’t even look up from his palette when he replied in a flat voice, ‘I don’t draw.’

He offered no more than that. Not, I cannot draw, but I don’t draw. No explanation. No apology. Nothing. As if we were made of clay and he the Creator. What kind of artist is he then? I’m no expert, but it seems to me an artist should at least have the skill to draw.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

We sit here day after day as he vanishes into that other room in his huge canvas—it must be more than ten feet across—coming out once in a while to look at us. We are statues to him. Models. Actors. Our lives disappearing, dissolving into thin air, vanishing into his great work. We are worth less than drying pigment.

‘Stop moving,’ he warns, when one of the boys adjusts his seat.

As long as he keeps putting coins in my pocket, I will sit here and put up with it, but I don’t have to like it.

* * *

He is so utterly obsessive, this damned artist. It seems he has to paint every single day, every moment that light is at the window. He never takes a day off but has us in here to pose for his great work, every day for weeks on end.

Once we are seated, except for occasional short breaks, we have been warned to remain still and in place. I spend hour s with my head turned as I stare at the models playing Jesus and Peter, my arm raised and aching as I point at myself as if to say in response to the summons, ‘Who? Me?’ I have nothing to do but listen and think. Bells, near and far, at every hour, tolling my life away. My head itching with lice to the point of madness. The wheezing, stinking, rotten-tooth breath of the old codger next to me. The gurgling of my stomach. The painter’s feet as he shuffles about behind the canvas. If I shift my gaze without turning my head, I can see him at work, that is, the lower half of him, moving back and forth. When he comes to the edge of the canvas to stare out at us, his tableau, he remembers precisely where he placed each model. If anyone has moved, even shifted in his seat slightly, he screams insults and threatens not to pay any of us. Finally, when we break for lunch, I, who never pray, offer up a quick paternoster in thanks.

What he does not know—well, I am not about to tell him. Me, I am no saint, as I said. I admit to having five murders on my head. Not accidents. Not outbursts of anger or hatred. Murders I committed without shame or hesitation, murders I plotted and planned, tracking my victims for days, months even, once a year and a half. I barely knew the men I murdered, only digging into their lives enough to discover their habits, where I would find them on a dark road, when they would have their guard down. I was paid handsomely. But that money is gone—posing for this artist today will pay for tonight’s meat, a gut-full of wine later, and perhaps a loaf of bread tomorrow to soak up my lingering hangover. Some saint I am.

Getting drunk is the only way I can forget the faces of the men whose throats I’ve slit. I said I murder willingly and without shame but their faces often return unbidden. That final look, it stays with you. But even more than getting drunk, I enjoy the hangover. I awake feeling as if my limbs are separated from my body, totally flattened, as if I spent the entire night banging my head against a stone wall (which I might have done—I don’t recall). My stomach feels like a storm at sea or a pot of boiling tripe soup. I admit I love that feeling of having been purged, emptied to the core. The necessary cleansing before the road to so-called recovery—and the next bout. And the next murder too, more than likely. For there will be another. After all, it is my profession, my own art.

Business is slow. This work as a model merely fills a temporary need. I did not seek out the artist. He noticed me on the portico of the Pantheon one evening, a place I go to gamble. He said I had the ‘perfect’ f ace, said I looked like a Jew though I wore no yellow cap, offered me a good handful of coins to sit for him in his studio.

This artist, this Signor Michelangelo Merisi, can afford to pay well. The favourite of the wealthy and famous Cardinal Del Monte, he lives upstairs in the cardinal’s palazzo. His fame grows as fast as mould on gutter-fruit. All Rome talks about him but, really, he’s no better than me. Several nights I have come upon him lying in the street, face in a pile of horseshit, stinking of cheap wine, having pissed himself. Quick with rapier and dagger too, he is. A real temper. They say he has taken part in numerous scrapes and dust-ups. Around Piazza Navona last week again. Insults the other artists. Most of them, anyway. Crazy.

I wonder if they feel much different in the hand: dagger and brush, brush and stiletto. Plunge into pigment, stab into canvas. Thrust your sword into your enemies, those saints and monsters. For a startling bright red, for a warm and brilliant scarlet, nothing better than to dip your brush into the boiling pot of a still beating heart . . .

The other evening on the street, I saw him talking to a young girl, running his hand over her black velvet sleeve as he roiled in the pleasure of the sumptuous cloth. I watched as he let his hand slide further up her arm, pretending to enjoy the cloth until he was stroking the soft flesh of her shoulder and neck. She barely noticed, believing he was still feeling the velvet nap. But it was the skin he was after, and it was her smooth, white skin he got. I watched from a distance. Too young to know any better, that girl. Probably about fourteen, and she works the streets. I see her out, not every night but once in a while. Why? Likely because she has to eat. Hunger is like that—fill the belly first, then worry later about sin and salvation. But I hate this Merisi. So arrogant, so full of himself. And I hate myself even more for not spilling his guts right there and then. But I need his coins.

Now he has dressed me for my role. Now I am the one in black velvet, as if I, Luca Passarelli, professional assassin, am a two-bit actor playing a saint or a gentleman with a floppy hat.

* * *

He titled the painting, The Calling of Saint Matthew. I am being ‘called’ all right—but not for any saintly or Christian duties. I know he saw himself as Jesus in that work. What a strange premonition. Jesus calls to me in the painting. Come follow me, Levi. I try to resist, pointing to the old fellow next to me. You mean him? You want him? No, Jesus says. I want you. Come follow me, Matthew, follow me into the world with your new name and your new life.

* * *

A few days later, I hurry in the direction of the Ponte Sant’Angelo on my way to another day of unbearable tedium in Merisi’s studio. As I place my foot on the bridge, I see that the executioner has been busy since dawn. Five fresh heads are mounted on posts on each side, flies at their eyes. The heads stare straight ahead, shocked at finding themselves suddenly dead. I have seen plenty of dead men in my day. I’m no saint. I have seen the faces of the men I’ve killed —I felt no hate for them. But they were grown men with blackened hearts and I simply needed the money.

Oftentimes, like today, I have passed the heads of the executed mounted on Ponte Sant’Angelo set out by the authorities as examples and warnings for those of us who might consider a life of crime. I usually pass by with barely a glance at the poor buggers, but this time I stop in my tracks. The fifth head on the right—I know him. We worked together on several murders. Enzo Rondini. Not an easy fellow. Always angry, he could turn on an accomplice in an instant. The fact that he had to slit a throat here and there in order to eat did not bother him, or me. In his youth, he had his ear cut off by the authorities for a long-forgotten crime. We live in hard times.

I stop and stare. That could be me up there. Probably will be someday. Well, we’ve all got to die, haven’t we?

I gaze at his head, gore still oozing from the neck, and an odd and unexpected thought comes to me—how would he paint it, this severed head? How would the artist present the look on Enzo’s face? What do I care how he’d paint it? But we cannot always control the thoughts that tumble into our brains when staring at the severed head of an old friend. I shrug and walk on, crossing the Piazza Rusticucci, a dull square with a trickling fountain in the middle and a trough for animals at one end. The image of Enzo’s severed head still flows heavily through me like the nearby noxious waters of the Tiber.

Later, in the cellar of the cardinal’s palazzo where I model and Merisi paints me as Saint Matthew, the artist shouts at me. ‘What is wrong with you today!?’ He leans out from behind his canvas, eyes bugged out. ‘The look on your face, it’s all wrong! I have told you over and over, I want a look of sur prise and expectancy and confusion. Not this visage of despair and sadness. Get out, I cannot work with you today. Get out! Everyone, get out!’

On my return from that accursed studio, I stop again on the bridge to see Rondini. I call him my friend but that is far from the truth. We were accomplices but that’s all. The flies still busy them-selves about his eyes and now maggots writhe in the gore oozing from his neck. Rondini does not look happy to be here.

I glance over the bridge’s parapet and notice three fishermen beside the Tiber, which is lined with low banks of garbage and refuse. A dead horse goes floating by as the fishermen are lifting a floppy sturgeon from their boat. Fish-head soup. The thought assails me. I want fish-head soup. But before I turn away to hurry to the tavern for soup I can afford, I take one last glance at Rondini the thief, the murderer.

Again, the question comes unbidden into my skull—How would the artist paint Rondini’s severed head? I recall as I left the studio earlier, I happened to glance over my shoulder at his canvas and thought, If beauty exists at all in this world of misery, this is it.

Standing on the bridge now, staring at Enzo’s head, the Tiber flowing beneath me, I wonder how it is that this arrogant pig of an artist makes me see the world through his eyes. I am angry. Angry for being dismissed by Merisi. Angry because I can barely find a way to fill my belly. Angry because the world is thick with misery and pain. I look again at the severed head of my so-called friend, stare into his eyes, and realize that at the heart of anger is profound sadness.

But I am no philosopher so the thought doesn’t stick.

_____________________________________________________________

Mark Frutkin is the author of over a dozen books of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. His works include the Trillium Book Award–winning Fabrizio’s Return (Vintage, 2006), which was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book, and Atmospheres Apollinaire (The Porcupine’s Quill, 1988), which was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award, the Trillium and the Ottawa Book Award. His latest book, When Angels Come to Earth (Longbridge Books, 2020), presents a visual and poetic appreciation of Italian culture. He lives in Ottawa.