Class, History, Fiction, and Form Part 5: The Speak o the Mearns

By Geoffrey Morrison

My parents are renters, so we moved houses a lot growing up. How can you expect continuity under those conditions, the steady passage of an uncomplicatedly teleological time? We can’t point to the place where a squirrel came down the chimney, or my brother split his head open while running around in inflatable pig slippers, or the balcony collapsed, because those were four, three, two houses ago. What do we have instead? Memories. Stories. Told over and over again, out of sequence and apropos of anything.

My mother’s memory is especially prodigious. She was born in Aberdeen in Scotland. She came to Canada as a nanny in the early 80s, but still remembers the full names of people in Aberdeen she hasn’t seen in over 40 years. She remembers her mother Molly’s “divi number” at the Co-op, where Molly got her first job at 14 serving tea. Her father, Bob, had a memory just as impressive, not least for poems and stories in his native Northeast Scots dialect of Doric.

It hasn’t escaped me that Bob’s childhood was also marked by moving around a lot. His parents were small tenant farmers who kept losing their animals to foot and mouth disease or running into trouble with their landlords (I’m proud to report that they sued one in court for £8 and won). One of the farms Bob grew up on was North Hilton in Netherley, in a part of Northeast Scotland called The Mearns. A description of this farm from 1901 describes it as having 25 acres arable. I don’t know if you know Scottish agriculture around the turn of the century, but that was small even then. That same year, a baby would be born in Auchterless (not far from Fyvie, the setting of a song that serves as an important motif in Falling Hour) bearing the name James Leslie Mitchell. At seven he would move with his family to a small farm in Arbuthnott, 16 miles south of Netherley. Against slim odds, he would become a teenage journalist, a socialist activist, and ultimately a writer, taking as part of his pseudonym an unusual name that had been his maternal grandmother’s and came from griasaich, the Gaelic for shoemaker (or, compellingly, embroiderer).

As Lewis Grassic Gibbon, he is best known now for his Scots Quair trilogy (Sunset Song, Cloud Howe, and Grey Granite), written in an incredible burst of energy before his untimely death from peritonitis, probably not unconnected to overwork, at only 33. I love these books. I think that whatever doubts you have about how to write political fiction, working-class fiction, fiction that decenters the individual agentive bourgeois character in favour of collectivities and polities and masses but also and at exactly the same time plumbs the inner depths of the psyche, dare I even say the soul (yes I do), these books have answered them already and will extend a kindly hand to you the moment you need them.

One of the things that makes the trilogy so special is its command of voice. Gibbon wrote before the doors of Scottish literature had been fully blown open for people just writing novels in their own spoken Scots. As such, he proceeded in a style which he describes, somewhat cheekily, in a note at the start of Sunset Song:

If the great Dutch language disappeared from literary usage and a Dutchman wrote in German a story of the Lekside peasants, one may hazard he would ask and receive a certain latitude and forbearance in his usage of German. He might import into his pages some score or so untranslatable words and idioms--untranslatable except in their context and setting; he might mould in some fashion his German to the rhythms and cadence of the kindred speech that his peasants speak. Beyond that, in fairness to his hosts, he hardly could go--to seek effect by a spray of apostrophes would be both impertinence and mistranslation.

The courtesy that the hypothetical Dutchman might receive from German a Scot may invoke from the great English tongue.

L. G. G.

It’s true. He writes in a kind of Doric-by-suggestion, keeping its “rhythms and cadence” and many dialect words (including “futret,” a word we often used at home to describe an annoying person but which literally means “ferret”) but avoiding the spellings that an English editor of the time would want to bury in “a spray of apostrophes.” The effect is nevertheless powerful. Reading this book, you constantly get the feeling you are following a free-running internal monologue reporting on events just a little bit after they have already been chewed over by nosy farm folk, townspeople, and factory workers. Whose monologue? Well, that’s the fundamental question. The answer seems to be – everyone’s, at one point or another.

Naturally the monologue often belongs to Christina (Chris) Guthrie, the deeply sensitive but also grittily practical protagonist of all three books, who goes from being the daughter of a harsh tenant farmer in a hamlet before the First World War, to the wife of an idealistic minister in a small town at the time of the 1926 General Strike, to the manager of a boarding house in the city during the Great Depression. We become richly acquainted with her inner life, and generations of readers have come to love her. And yet, through Gibbon’s masterful use of free indirect discourse, we also hear the voices of other people who can’t stand her, often out of class prejudice or political animosity, as here in Cloud Howe:

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“Mr. Mowat never went near the Manse now, he hadn't done that since the days of the Strike, nor the Geddeses either since Mrs. Colquohoun had raised a row at the W.R.I. And what do you think that row was about? A socialist creature had offered to come down from Dundon and lecture on birth-control: and all the folk were against it at once, except the tink bitch the minister had wed. . . . And what might IT be? you asked, and folk told you: just murdering your bairns afore they were born, most likely that was what she herself did.”

Who is “you,” here? It’s a real hallmark of Gibbon’s style that we kind of don’t know. Or rather, it doesn’t matter exactly who, because “you” is legibly a member of a chattering chorus of small-town snobs, the small business owners who sided against the workers in the General Strike. The voice is particular yet general. It doesn’t need to belong to a character in a strict sense.

Gibbon was a committed Marxist, but he often relates political developments and mass actions through the anonymized voices of people who are not – people who are on the fence or even actively hostile. This is another version of Barthes’s insight, in “The Poor and the Proletariat,” about seeing someone who does not see – but in this case we have moved further away from defined characters as the vehicle for that process. It also allows us to feel like we are not just reading propaganda, which makes it incredibly effective political writing. Once again, we at home have been given the tools we need to solve for X.

Gibbon’s facility with free indirect discourse also means that the very identities of his characters are constantly in question. As a peasant girl who first marries a farm labourer from the Highlands, and, after his death, a minister, Chris Guthrie is constantly being rendered, through the voices of people who don’t like her, as either too common or too stuck-up. Similar things happen to her son Ewan when he goes to work in a factory in the city. At first his aloof bearing and reluctance to speak Scots mark him out as a “toff” in the eyes of the other workers, but later when he becomes a Communist the management think of him as a brutish “thug.” These competing and contradictory visions are always triangulated in a very sophisticated way by Grassic Gibbon the embroiderer.

I think this was basically what Bakhtin meant by “heteroglossia” – language erupts onto the scene as a kind of intimate social fingerprint and shows us something of the world that made it (and thus makes us). And it’s not a coincidence to me that Bakhtin was such a student of the 16th-century French satirist François Rabelais, whose books are full of the blunt remarks of peasants, the Latinate pretensions of scholars, and everything in between. Reading Rabelais, you get the sense that he could do anything, as you do with many writers of the 16th and 17th centuries. Oral culture was not dead, literacy was reaching more of the population, and print culture had not firmed up into a set of expected rules. This meant that Rabelais and his peers were not writing novels. They were writing the things that came before and will come after. Animals, inanimate objects, the dead, even books themselves – all are given voice, with something almost approaching the absolute freedom of the oral storyteller to range digressively across time and space, singular and plural. If characters are the private atoms of capitalist modernity, then voices – even inner voices – are social, historical, and shared.

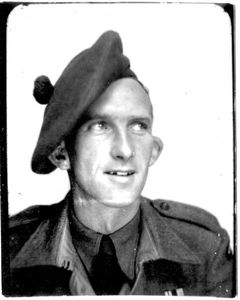

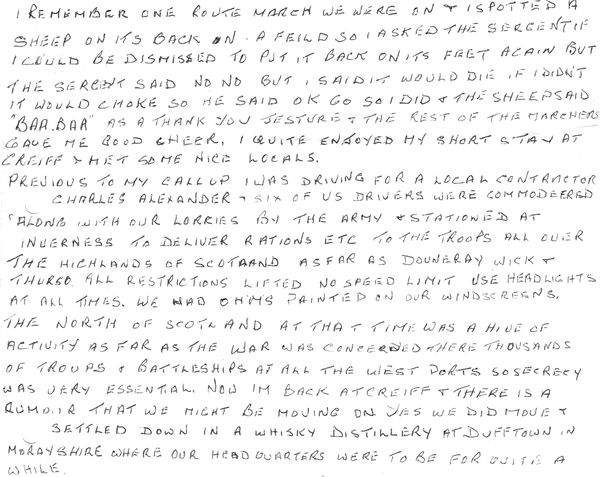

When Grandpa Bob was in his 80s, and I was about 5, my mother asked him if he might want to write to me about his memories of the Second World War. He had been a driver in the Signals for the 51st Highland Division, and had been in North Africa, Italy, Normandy, the Netherlands, and Germany. Bob was conscious he was writing to a little boy in another country, and so, just like Lewis Grassic Gibbon, his prose is more Doric by syntactical suggestion than in content (though when he came to Canada to visit he liked to speak to me in Doric; he would even quiz me to see if I understood him). But it is unmistakably his voice.

At one point, Bob saves a sheep while on maneuvers in Crieff, Perthshire, digresses to describe how, as a civilian lorry driver for a shipping company before conscription, he and five other drivers had been commandeered for war work, and then returns to Crieff mid-paragraph: “Now Im back at Crieff & there is a rumour that we might be moving on yes we did move & settled down in a whisky distillery at Dufftown in Morayshire where our headquarters were to be for quite a while.” When I’m talking about voice and the absolute freedom of the oral storyteller to leap across time and place, to digress, to be meta, this is what I’m talking about. Yes, talking, even though, on paper (ha), I’m writing.

As a person who lives on “worker time,” who is never sure if I’m going to pull it off, who went to university though my parents did not, I have often felt bitter about all the shortcuts to be had by people who have always had money, who do not have to work, who seemingly inherit flawless opinions fully-formed. But seeing my grandfather leap across time and space in his letter to me is a deep and abiding consolation. They have their shortcuts, and we have ours, and I humbly submit that ours are older and will endure longest.

Well now. I think that about wraps up my attempt to say what I think about fiction and class. If I have loose ends, I will tie them later. I want my dessert.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Geoffrey D. Morrison is the author of the poetry chapbook Blood-Brain Barrier (Frog Hollow Press, 2019) and co-author, with Matthew Tomkinson, of the experimental short fiction collection Archaic Torso of Gumby (Gordon Hill Press, 2020). He was a finalist in both the poetry and fiction categories of the 2020 Malahat Review Open Season Awards and a nominee for the 2020 Journey Prize. He lives on unceded Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh territory (Vancouver). Falling Hour is his first novel.