Letters that were never intended for me

By Lindsay Zier-Vogel

It’s no secret that I love letter writing. My debut novel, Letters to Amelia, is full of them, and I even created an entire community arts project based around the power of writing letters. But with (real) letters (not letters written in a novel, ha!), after you slip the envelope into the mailbox, you have no record of what you wrote. You can’t refer to a sent folder and dig up what you sent. As a writer to keeps every single draft of every single piece of writing, there’s something so liberating and freeing about sending words out into the world, and not ever being able to revisit, or even, at some point, remember what I wrote.

Except a few weeks ago, I met up with an old friend from thirty years ago, and she handed me a pile of letters. My letters. Letters I’d sent her from 1992-1995.

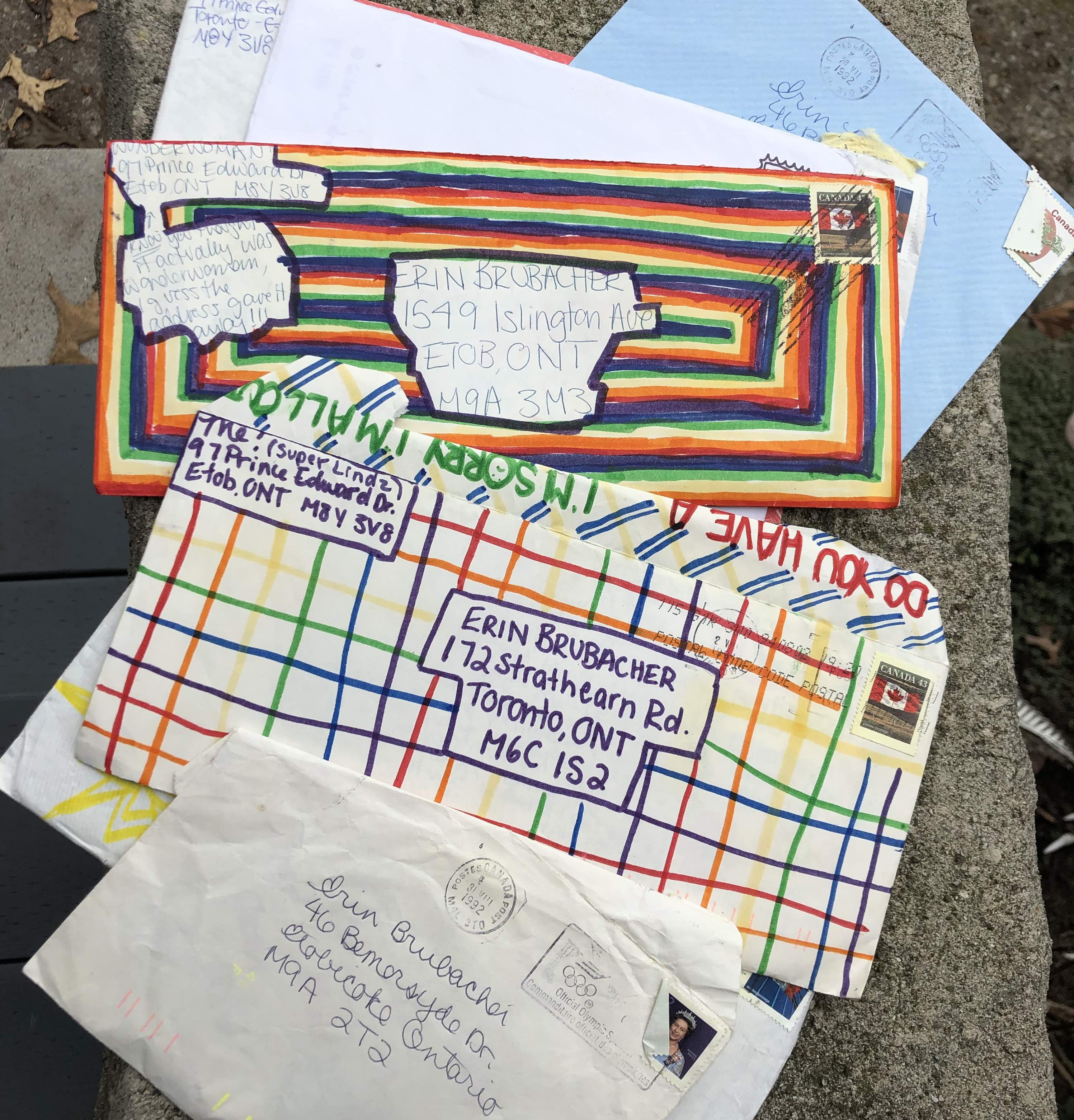

The envelopes are decorated with Crayola markers, and illustrated in-jokes I vaguely remember, but also can’t place (what was the Island of Naboomboom? Why did I call her “Leechie”?). Most envelopes contain multiple letters, each many pages long. I’ve always been a word count maximalist.

I was instantly transported back to the days when we were terrified of bleeding through our jeans, and taught each other dance routines in front of the lockers near our homeroom and Jeff was “Cal” and Sean was “Vinnie”, Matt WS was “Klein” (the secret codes for our crushes, named after Calvin Klein’s “Obsession”).

There were a lot of very cringe-worthy moments—infatuations with boys who had no idea I existed, verbatim conversations with boyfriends (and their sisters, apparently), and more boys, and a detailed account of the first time I’d taken the moving sidewalk at Spadina station. I wrote, “Wowy-smowy” a lot, and used the work “funk” more than could ever possibly make sense.

But, near the end of the pile, I read a passage that really stuck out: “Y’know what I’m so scared of? Growing up, cuz when you grow up you forget and I’m already starting to forget things that used to be so important. EXAMPLES: Up until two seconds ago, I totally had forgotten that I ever went out with Matt Gibb! It’s not a big thing, this this is something I shouldn’t forget in just a year.”

I wanted to reassure thirteen-year-old Lindsay that growing up was awesome. I mean, some parts weren’t, but 37+ was really amazing. I wanted to reassure 1993 Lindsay that though I wouldn’t forget going out with Matt Gibb, it was okay to forget things, and that the important things would always stay close, and that, funnily enough, I wouldn’t forget a bunch of things because I’d be reading that exact letter twenty-eight years later.

These letters inspired me to dig around in my basement, where I found not a binder I got after my grandparents died with every single letter I’d ever sent them. From scribbled thank you note transcribed by my mom before I could write words, to the illustrated letters I wrote in high school, to every single angsty poem I ever sent them, to the piles of thank you notes for every single birthday gift, every single Christmas gift—they’d kept them all.

I found a series of thank you notes in bright Crayola that I had written them from Algonquin Park, where I was a counsellor for one summer in 1997. It was the first time I’d been away for a whole summer, first time I’d ever been in Algonquin Park, and they sent care packages twice a week.

When I remember that summer, I remember it in the photos I took—the dress up days where I was a Spice Girl, or Princess Leia, the skinny dipping, the hemp necklaces, and the day-off shenanigans at someone’s nearby cottage. But in the letters, I wrote about how anxious I was about campers arriving, about a loon that swam next to me for the length of a lake on a canoe trip, about the eight (!) moose I saw on one camping trip, that I used the money they sent up in a care package to take my campers out of ice cream—things I have no recollection of.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Though I can’t remember writing any of these letters—to Erin, or to Nana and Papa—they hold more of those moments than a photo every could. They aren’t just time capsules of 1992, of 1997, they are time machines, instantly taking me back to previous versions of myself, unphotographed moments of myself. It’s strange and surreal to have these words, words that were not intended for me, words I didn’t ever intend on reading again, this deeply intimate record of myself.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Lindsay Zier-Vogel is an author, arts educator, grant writer, and the creator of the internationally acclaimed Love Lettering Project. After studying contemporary dance, she received her MA in Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She is the author of the acclaimed debut novel Letters to Amelia and her work has been published widely in Canada and the UK. Dear Street is Lindsay’s first picture book, and is a 2023 Junior Library Guild pick, a 2023 Canadian Children’s Book Centre book of the year, and has been nominated for a Forest of Reading Blue Spruce Award. Since 2001, she has been teaching creative writing workshops in schools and communities, and as the creator of the Love Lettering Project, Lindsay has asked people all over the world to write love letters to their communities and hide them for strangers to find, spreading place-based love.