"We Approach the Mystery [of Art] in Bafflement... Not in Sureness": A Conversation with Award-Winning Poet Kate Cayley

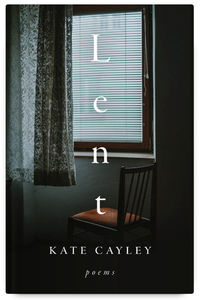

Decorated multi-genre writer Kate Cayley's new poetry collection, Lent (forthcoming from Book*hug Press) is one of her most exciting books yet, and that is saying something, given that her previous works have racked up honours like the Trillium Book Award and nominations for the Governor General's Literary Award, the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize, and the CBC Literary Prizes in both fiction and poetry (to name just a few).

Lent explores the strange times we live in, where ever-increasing individualization and separation from community drives us towards isolation and smaller and smaller groups, while doomsday politics and climate disaster loom ever larger. This simultaneous shrinking and expanding of our mental and emotional landscapes is captured in crystal-cut domestic tableaux juxtaposed against big questions of life, love, philosophy, and faith.

Cayley is sure-footed, evocative, and expansive as she walks readers through tightrope-taut poems that capture both the dread and hope of the 21st century. Familiar details of children and the home filter through fascinating and unexpected speakers like Mary Shelley and Assia Wevill, the latter of whom was the partner of poet Ted Hughes after the death of his first wife, Sylvia Plath and became obsessed with Plath.

Ever balanced, wise, and filled with the unexpected, Lent is both deeply of its time and beyond it, showing how dread, love, rage, and hope act as the timeless silent backdrop of seemingly quotidian scenes, and how the spectacular lurks just below the surface of the everyday.

We're excited to speak with Kate about Lent today as part of our Line & Lyric series. She tells us about how she's observed over her writing life that "writers only have a few subjects, images, or obsessions that we have to keep returning to", why the Christian concept of giving something up for a time—as explored in her title poem—fascinates her right now, and why before beginning Lent, she spent years thinking she might never write poetry again.

Open Book:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

Kate Cayley:

Lent, the title poem, is a long prose poem that I began writing, hesitantly and in fits and starts, about five years ago. I was on a writing retreat for a week, the first time I’d done such a thing, and a lot of questions came up because of the silence. I’m married and have three children and our household is pretty social, so the silence was remarkable and a bit terrifying. When I began writing Lent it was to avoid the book I’d gone there to work on in the first place, but the poem just came and felt like a slow and necessarily only partial working out of a lifelong thought about religious faith and doubt and how this relates to art and to how we see the world. I think (and I’ve got other writers backing me up on this) that writers only have a few subjects, images, or obsessions that we have to keep returning to, that can’t be avoided. Lent felt like that for me. I wrote it in fragments, somewhere between a lyric and an essay, because it was the only way to write it, to find a form that tried to live in the unease of ongoing questions, not in conclusions. It was the spine of the collection. In the context of the poem, Lent is the Christian observance in which you must give up something, which seems important to me right now, to think about what it means to renounce something, to impose limitation. So much of our current predicament is tied to our refusal of limitations, of reasonable restraints. We want everything, all the time, and it’s going to kill us. And the word Lent also evokes how temporary we are, how much our time is a loan and something we will not keep. It had to be the title of the collection.

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

KC:

Writing it at all. I last published a collection in 2017, and after that had a despairing period in which I didn’t seem to be able to write poetry. I don’t want to be too melodramatic—I was working on other things happily. But no poems came and I thought I might never write poetry again. It’s such a nebulous thing, writing a poem, what suggests it, how it peels off the wall of your mind. You can’t force it. And I was weirdly (and a little sadly) resigned, thinking oh well, that’s done. Then suddenly the poems came back. I was very surprised and very pleased.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

KC:

This collection, like most of my books past and to come, is dedicated to my wife Lea. Because I’m really lucky to have her.

OB:

Is there’s an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

KC:

I write a lot in the voices of others, real people and imagined ones. This collection was more in “my” voice than anything I’d written before, but that’s a performance too, of course. Even writing as yourself, maybe especially writing as yourself, you assume a voice. But I love writing as a character (this might be my past as a playwright). There is a series in the collection in the voice of Assia Wevill, Ted Hughes’ partner after Plath’s death. She was obsessed with Plath and killed herself in the same manner, along with her daughter, only a few years after Plath. Her voice began the work on the collection, in fact. Mary Shelley is in there, too, and some figures from Dutch Masters. They all showed up and started chatting.

OB:

What advice would you give to an emerging or aspiring poet?

KC:

Read everything. Read poetry but also novels, essays, even plays. Read work in translation and work by dead people and people with whom you do not necessarily agree, either aesthetically or politically. That said, allow yourself to love what you love without second-guessing—we all have to stand somewhere, be at home somewhere. Measure yourself against what you love without despairing too much about how far you fall short. Cultivate a spirit of ambivalence. I don’t think absolute moral certainty and art can occupy the same space. Art comes out of ambivalence, a sense that the world is bigger and more various than we are capable of comprehending, that we approach the mystery in bafflement and humility, not in sureness. Have a sense of humour about rejection, insofar as that’s possible. This is a really long game, being played largely invisibly, so we all need to find ourselves ridiculous and take ourselves seriously at the same time.

OB:

For you, is form freedom or constraint in poetry?

KC:

Both. I don’t start with form. An image or a line (or a voice) comes, usually through repetition. You walk around thinking of a line and you don’t know where it arrived from, but it definitely arrived. You didn’t make it. There’s no form yet. But when the line or image or intimation of a voice becomes a poem not the beginning of one, then you have to start thinking in terms of constraint: the echoes in the words themselves, the rhythm that propels the reader and is intertwined with the meaning of the poem and is part of the meaning. There’s a wonderful meditation in a Wendell Berry essay called “Standing by Words” in which he dismisses the rejection of pattern on the grounds that what is formless is what is free. I can’t remember the exact line but he says that nothing in the world is without form, without pattern or rhythm, except nuclear waste sites and battlefields. They are true chaos. Everything else, even the ostensibly formless, must call upon a pattern, a symmetry. Rejecting that symmetry isn’t freedom, it’s destruction. This makes sense to me.

OB:

What are you working on next?

KC:

I’m currently working on a novel (aren’t we all) and a third short story collection, alongside two theatre projects in collaboration with Zuppa Theatre, an immersive company based in Halifax that I often work with. Also, Book*hug is going to reissue a tenth anniversary edition of my first collection, How You Were Born, in 2024, with some new stories. So I’m working on that too, which is an amazing gift.

_________________________________________________

Kate Cayley is the author of two previous poetry collections, a young adult novel, and two short story collections, including How You Were Born, winner of the Trillium Book Award and shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. A tenth anniversary edition of How You Were Born is forthcoming from Book*hug Press in 2024. She has also written several plays which have been performed in Canada, the US, and the UK, and is a frequent writing collaborator with the immersive company Zuppa Theatre. Cayley has won the O. Henry Short Story Prize, the PRISM International Short Fiction Prize, the Geoffrey Bilson Award for Historical Fiction, and a Chalmers Fellowship. She has been a finalist for the K. M. Hunter Award, the Carter V. Cooper Short Story Prize, and the Toronto Arts Foundation Emerging Artist Award, and longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize, and the CBC Literary Prizes in both poetry and fiction. In 2021, she won the Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry for the title poem in Lent. Cayley lives in Toronto with her wife and their three children.

![Banner image with photo of author Kate Cayley. White text on purple background reads "This collection [is] more in 'my' voice than anything [I've] written before. Interview with Kate Cayley" Banner image with photo of author Kate Cayley. White text on purple background reads "This collection [is] more in 'my' voice than anything [I've] written before. Interview with Kate Cayley"](/var/site/storage/images/media/images/open-book-kate-cayley-interview-lent-2023/113929-1-eng-CA/Open-Book-Kate-Cayley-interview-Lent-2023.jpg)